What if Congress had more than two parties?

Proportional representation could create a more functional Congress. A new report outlines how and why it just might work.

As dedicated readers of this newsletter know, I am a strong advocate for a multiparty democracy in the United States, particularly through proportional representation and fusion voting. However, in advocating for these changes, I often encounter skepticism about governability: if Congress struggles to function with just two parties, imagine if it had six!?

I take governability seriously. My interest in electoral system changes emerged from my previous work trying to build up congressional capacity.

Working on congressional capacity, I realized congressional dysfunction, centralization of power, and binary hyper-partisanship were all the same problem – interlocking cogs in the same sputtering governing machine.

As I wrote in Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop, “a fully divided two-party system is decidedly unworkable in America, given our political institutions. We have a separation-of-powers government designed to make narrow majority rule difficult to impossible. And yet we have a party system where both sides attempt to impose narrow majority rule on each other. The mismatch is unsustainable.”

This insight led me to electoral reform. I wanted to break the destructive binary. So here I am, years later, screaming about proportional representation and fusion voting.

But I do admit, the growing electoral reform movement often ignores governance. Instead, it prioritizes the voter experience and descriptive representation. That’s all important, and arguably, the strongest selling points of reform.

But if we don’t have a functional Congress capable of solving hard problems with legitimate solution, descriptive representation doesn’t add up to much

This is why I’m so delighted to introduce my new New America report, “Governing the House with Multiple Parties,” co-authored with Rob Oldham – It tackles the governance question that motivated my initial interest in electoral system reform.

Our report is, yes, long and wonky. Well, what did you expect? A beach-read mystery novel? Sorry. Not here. This is serious scholarship. We grappled with history, comparative politics, and the hard problems of governing in any system. It’s a compelling read … to me!

I don’t want to over-sell this report as a slam-dunk case that proportional representation will guarantee a more effective government. It’s important to be honest that there are no “silver bullets.” But having spent a year with Rob wrestling through all the trade-offs and uncertainties, I come away seeing much more upside than downside to a proportional multiparty Congress.

Our report examines not only what we think would happen. We also explore what we think should happen. We draw some best practices from around the world, and also from state legislatures here in the good old U.S. of A.

Mostly, our recommendations are in line what congressional reforms have been advocating for years – a more decentralized Congress, a more committee-driven process, and more fluid issue-driven coalitions. And I have long agreed – this governing approach would make for a more functional, creative problem-solving Congress.

But there is a reason Congress hasn’t returned to this vision of “regular order,” despite the well-articulated arguments of many scholars. The reason is that a polarized two-party system and top-down, centralized leadership are two reflections in the same terrifying hall of mirrors, and we are trapped in the doom loop of reflections. So… maybe it’s time to smash the mirror?? Or, less violently, to exit the binary, polarized two-party system, by adopting multiparty proportional representation.

Below, I’ll offer some highlights from the report – a mere sampler platter that can’t possibly do justice to the nuance and complexity of the full report – which is definitely worth printing out, right now, to take to the beach for when you tire of that predictable, all-too-formulaic mystery novel. But for those who just want the highlights, read on. I see you.

Our point of departure will be the current Congress, which makes one killer argument for shaking things up.

The 118th Congress and the limits of centralized two-party government

The 118th Congress, now in its final months, has been a very strange Congress.

Most memorably, a small rebel faction ousted the Republican speaker, and then Congress went almost 22 days paralyzed without a Speaker. The dysfunctional chaos contributed to record-setting wave of voluntary retirements, including many talented and institutionally-minded members who were quite vocal in their disappointment and disgust. (I wrote about this talent exodus here)

Since the late 1980s, the US House of Representatives has operated under increasingly centralized leadership structures, concentrating more and more power in the office of the Speaker. In the 1980s, modest centralization made sense. Individual members were demanding stronger party leadership to bring order to the institution and sharpen the contrasts between the two parties, whose distinctions were then quite muddled and overlapping.

But over the last four decades, American politics has changed considerably. Political observers from the 1980s would find our currently hyper-nationalized parties, polarized into hyper-distinct coalitions, unrecognizable.

The two parties have voted in more predictable partisan lock-step with each subsequent Congress. But this tightening and separating of the coalitions has suppressed considerable internal disagreement. Parties have sorted and polarized, yet America has become diverse across many dimensions.

Thus, as we write in the report:

The 118th Congress demonstrates how the considerable diversity and heterogeneity in American politics are in tension with centralized leadership in a two-party system. The two parties have always been “long coalitions” of diverse policy interests, congealed by a constructed ideology that binds a coalition around agreements and sublimates divisive disagreements. Moreover, there have always been elements of those coalitions that have been dissatisfied with their place in it. The changing variable here is the centralization of legislative leadership after decades of rising polarization, partisanship, and electoral competition. Empowered party leaders have sidestepped disagreement in pursuit of the one goal everyone agrees on—defeating the other party. However, if a highly centralized House cannot accommodate a resurgence in intra-party factionalism, this arrangement is in trouble.

This problem is unlikely to be solved by reforms that further empower the two parties to discipline their members. The larger issue is that the centralization created by polarization and electoral competition does not fit with a broader governing system that requires power-sharing and compromise. Our electoral system has pushed us into two camps, but American politics is much more complicated than this superficial binary. If members decide that it no longer suits their interests to bury their disagreements in service of the two-party system and defer to strong leaders, they could alter institutions to achieve their goals through other means.

We see this tension between top-down leadership and intra-party conflicts as a condition rather than an episode.1 So perhaps it’s time Congress did something to resolve that tension — like implement proportional representation for Congressional elections.

Proportional representation as a governance reform

Let us imagine that Congress passed a law requiring all states with at least three representatives to adopt proportional representation to elect their Congressional delegation. Most representatives would come from states with proportional representation, and multiple parties would have representatives in Congress.2

How might such a Congress operate?

To make our best guess, we looked at the many democracies that use proportional voting systems to elect multiple parties to their legislatures. Multiple parties forming coalitions is normal in these democracies. Party leaders negotiate amongst themselves over power-sharing and priorities. Eventually they reach an agreement and form a government. Typically, it takes a few weeks, occasionally two months - the same as the gap between elections and new Congress seating.

Since the United States is a presidential democracy, we look in our analysis mostly to other presidential multiparty democracies, which are the norm throughout Latin America. Though an older conventional wisdom suggested that presidentialism and multipartism did not always work well together, recent decades have shown that presidentialism and multiparty democracy can work just fine together, as Scott Mainwaring and I document in a white paper we released last year, “The Case for Multiparty Presidentialism in the U.S.”

I wrote about our analysis here, in a piece titled “Proportional representation and presidentialism work just fine together”:

In multiparty presidential systems, multiple parties often form pre-electoral coalitions, organized around one presidential candidate, to avoid vote splitting. Imagine, for example, if the United States were a multiparty system, you could imagine a three-party coalition united in support of Kamala Harris for president. A progressive left party, a mainstream centrist Democratic Party, and a center-right “rule of law” party. In proportional Congressional elections, voters could choose any of the three parties, to shape the balance of power in Congress. However, for the presidential election, they would all unite behind the same candidate. Fusion voting for presidential elections would strengthen this, allowing voters to support their preferred party.

Post-election, intense negotiations would occur. As we write:

The pre- and post-election negotiations would almost certainly involve bargaining over positions with agenda-setting powers, like committee chairs and cabinet seats, and the final negotiated agreement would likely match policy jurisdictions to party interests. For example, if the left bloc controls the House, a working-class labor party might control the committee with jurisdiction over labor, while a party supported by knowledge economy workers might control the committee with jurisdiction over tax policy. In addition to committee chairs, the coalition would have to decide on leaders who would manage their procedural majority more broadly, including the House Speaker. These coalition leaders would probably be drawn from the ranks of the individual party leaders.

We expect governing majorities would generally alternate between a left-bloc coalition and a right-bloc coalition, as they do in most multiparty democracies, both presidential and parliamentary. But the coalitions would have some shifting overlaps from election to election.

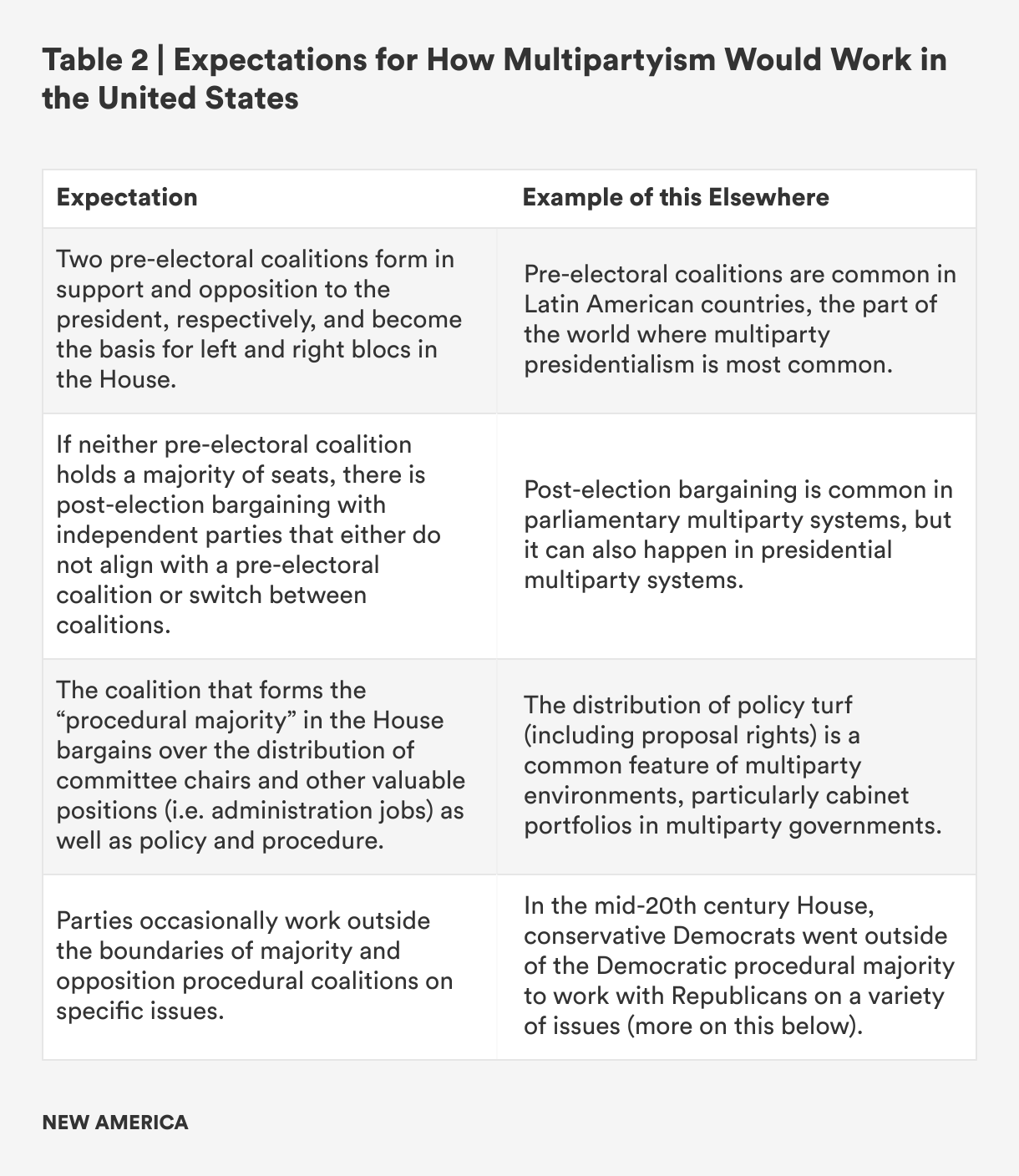

We broadly summarize our expectations in the table below, drawn from the paper.

In this way, we envision a future multiparty Congress resembling the mid-20th-century Congress, which was far more decentralized and committee-driven than today’s Congres. The mid-century Congress was like a multiparty Congress, with a rough four-party system: Liberal Democrats and Liberal Republicans, alongside Conservative Democrats and Conservative Republicans. Because the coalitions were different across different issues, Congress was able to work out broad bipartisan deals across a range of issues.

Would a multiparty Congress lead to better governance than the current two-party system? Certainly, there are both comparative and historical reasons to think it might. In general, proportional systems are associated with effective and responsive governing outcomes (though obviously other factors are important, and not all proportional systems are the same), as my New America colleague Oscar Pocasangre and Dartmouth political scientist John Carey concluded in an extensive review of the literature on how electoral systems affect governance.

But there are obviously many ways in which a multiparty Congress could turn sour. So in researching and writing the paper, we devoted considerable effort to thinking through some potential best institutional practices that we think would work well in a multiparty Congress.

Some thoughts on how a multiparty Congress should work — more decentralization, stronger committees

Our recommendations for a multiparty Congress align with those of congressional reformers, emphasizing a decentralized, committee-driven approach. This would increase opportunities for member participation in lawmaking and facilitate bottom-up compromises. As we write in the report:

Our key recommendation for unlocking bipartisan collaboration is decentralizing the legislative process in ways that empower committees and latent policy majorities while preventing leaders from concentrating power. This should look similar to what scholars call “regular order,” which describes a process where committees and members develop legislation through deliberation and consultation without undue influence from legislative leaders. When bills pass out of committee with a majority vote, they then come up for a vote on the House floor. On the House floor, all members debate and deliberate, and ultimately cast an up or down vote on the bill. Many scholars have a preference for this process as superior to the top-down leadership-driven process, arguing that it fosters more serious policy engagement from a diversity of members, ultimately producing better policy….

This doesn’t work in the current system because leaders decide what legislation makes it onto the House floor. Leaders are particularly likely to block legislation that is opposed by a significant chunk of the majority party, even when it is supported by a majority of the entire House. This practice of blocking bills without the support of most majority party members is known as the Hastert Rule.78 Party leaders enforce the Hastert Rule (which is not actually a rule but rather a convention) because they want to avoid intraparty feuds and criticism, particularly if those feuds threaten their jobs. This is essentially why Johnson blocked immigration reform—allowing a vote would have angered many members of his caucus by undermining the party’s political messaging.

We also offer some specific ideas for how governing coalitions should negotiate over committee roles, and how a more open agenda-setting and voting process (but not too open) could work (and why it would be more likely to succeed in a multiparty party congress, than in our current two-party Congress). As we write:

First, multiparty bargaining almost necessarily means that committee positions and chairs would be allocated through negotiations among the parties rather than through a top-down process, like steering committee selection If a party cannot get its preferred committee appointments through negotiation, it might not agree to cooperate with the procedural coalition on other matters (or may even join the opposition). Factions would have more leverage in a multiparty system than in our current system because withdrawal is a far more credible threat than in a two-party system.89 Bargaining over committees would essentially mirror what happens in other multiparty democracies when parties negotiate over cabinet ministries. …While the bargaining over committee chairs might occasionally lead to chaos, it would be fairer than the seniority system, which allowed southerners to dominate the committees in the pre-1970s period, and the current system, where committee appointments are often driven by party loyalty and fundraising prowess.

We both expect and recommend a less powerful Speaker of the House, more in line with the mid-20thcentury speakership. We suggest a more powerful Rules Committee, in which coalition partners would share power and control of the floor agenda, as well as some guaranteed committee access to the floor.

We also suggest protections against removing a speaker mid-Congress. We elaborated on this idea of a constructive vote of no confidence in a recent Politico opinion piece.

We summarize our proposals for making a multiparty House work more effectively in the table below.

We see most of these ideas as good governing practices, regardless of party count in the House. However, a multiparty House would be far more likely to adopt these proposals, because the current two-party binary almost demands a top-down centralized leadership structure.

But… What about the Senate?

The Senate presents a potentially challenging obstacle since Senate elections are inherently single-winner, and inhospitable to proportional representation. It is certainly possible that the Senate might follow a proportional House towards multipartyism. The Senate could operate with more traditional free-flowing coalitions. Fusion voting for Senate elections could help translate some multiparty activity into single-winner elections.

Still, as we note in the report, the Senate’s “minoritarian impulse is exacerbated by the body’s malapportioned structure as smaller states that are more rural, white, and conservative have more representation relative to larger and more urbanized states where liberals and racial minorities are concentrated. As such, even if a multiparty coalition representing a majority of the country was able to take action in the House, senators representing a minority of the country could still block them”

Perhaps the same burst of institutional reform energy that will be necessary to bring proportional representation to the House would also spur a re-thinking of the United States Senate, which is a distinct outlier among upper chambers in contemporary democracies in both its extreme malapportionment, its conservative bias, and its formal powers. I explored this topic in a separate Undercurrent Events, “Wither the Senate?”

“Escaping bad equilibriums requires imagination, bold ideas, and deep thinking about systematic change”

Electoral reform is in the air. Serious people increasingly acknowledge that our current political dysfunction won’t self-correct. A logical conclusion follows: we need structural democracy reforms to get our political system “working” again.

I use “working” in quotes because people toss around this word loosely, to mean very different things. I admit, I have no precise definition either, though if pressed, I would lean on familiar metrics of productivity and legitimacy. Mostly, I think about this in a framework of adaptability and resilience. A governing system that works is a system that adapts to the challenges of the current political environment, and is resilient to the many threats that have challenged democracies throughout history, and continue to challenge them today.

Can Congress adapt and change in the current environment?

As I explored in a different Undercurrent Events, the U.S. House of Representatives has re-organized itself throughout the history of American democracy, cycling through various iterations of centralized and de-centralized power. Throughout different iterations, changing coalitions governed Congress. But regardless of the rules, majority coalitions always managed to organize and govern. I wrote about that history in a piece here entitled “There are many ways to organize a House of Representatives. Not all involve a powerful speaker.”

The adaptability of our national legislature has been the key to its survival. Can it do so again? Or will it get stuck in a sub-optimal arrangement that cannot survive the current environment, and disappear from this earth?

We’ve never faced a moment like this before. Uniquely high levels of polarization, uniquely low levels of competitive districts, and a uniquely radical Republican Party, among other historical rarities. I called it Uncharted Territory, as I wrote here in a piece entitled “The U.S. House has sailed into dangerously uncharted territory. There’s no going back.”

If our system of constitutional republican government is going to survive, it will need to change course and adapt. Will it? Does it still carry the capacityfor growth within it?

I’ll close by quoting the final paragraph of the report:

Comprehensive institutional change is difficult. Uncertainty and unintended consequences lurk around every corner. However, not changing our institutions also entails risk. Escaping bad equilibriums requires imagination, bold ideas, and deep thinking about systematic change.

I hope our report starts a broader conversation about governability and electoral system change. We certainly don’t have all the answers. But maybe at least we are asking the right questions.

to borrow Nancy Pelosi’s dichotomy in assessing Biden’s June 27th debate performance

I will here leave out the specifics, but assume a modest district magnitude that keeps the number of parties to around five or six.

One wonders what is possible. That is, where can we find analysis that goes beyond "what would be nice" (proportional representation in House, fusion voting for single districts, a Senate whose members had voting power based on state population, etc.) and looks for politically possible paths to get there. Looking for the "possible" acknowledges the constraints imposed by a constitution designed to be incredibly difficult to change, a public that has lost hope and has seemingly become convinced that government does not need taxes to function (given that federal debt is already past 100% of GDP).

My repeated focus on campaign finance reform using vouchers has the advantage that all it requires is passage of a simple law with a modest budget and a sturdy stare-down of our reactionary court (some members of which are on very thin ice). It could be extremely popular with the public if creatively sold. Unfortunately, to be convincing to the public, I suspect its advocates would need to publicly back away from some of the biggest sources of funds (especially the big financial institutions that are currently in such delicate condition). Courage is required. Given the unpopularity of the Republican party's candidate, the current House majority and abortion-happy Republican state legislatures, maybe such courage is a reasonable bet.

Would vouchers solve the problems Lee addresses? No. But they might buy some time, be a source of hope and reduce the fund-raising pressure on those elected. If thinking came back in fashion, maybe "paths" could be found.

Thanks!

The (obvious, I suppose) next important question would be to identify self-enforcing transition pathways, ideally considered both through an analytical (model) and an actor perspective: who might do what - in line with their self-interest - in order to collectively coordinate into such a novel institutional equilibrium.

If such a transition pathway exists at all. But, under Knightian uncertainty and in light of the potential welfare gains, certainly worthwhile exploring.