There are many ways to organize a House of Representatives. Not all involve a powerful speaker.

A short history lesson to expand our imagination.

The U.S. House of Representatives continues in its self-induced legislative paralysis, approaching 22 days without a Speaker.

This raises a question: Aren’t there other ways to organize a legislature? And while we’re at it: Why is the Speaker of the House so powerful? Why is the Speaker of the House even a partisan officer?

Stay tuned. I have answers. Or at least thoughts that might be answers.

I can imagine many different ways in which the U.S. House of Representatives could organize its business. In fact, over more than two centuries of operating, it has organized itself in many different ways. My imagination is historically inspired.

Reviewing this history has helped me to see alternative possibilities. And I hope it will help you, too. I write to serve my country, after all.

I laid out some of this thinking recently in The Atlantic, in a piece titled “Matt Gaetz is Half Right” (you’ll just have to read it to find out why he’s half right, won’t you now?).

But here, I’m going deeper, with all that nerdy wonky detail I know you love. So here goes. Grab your history party hats, and let’s get started.

How Do You Organize a Legislature, Anyway?

Before we dig into the history, let’s play a little party game to warm up. It’s called “Legislative Organization.” And trust me, it’s harder than it looks.

Imagine you have, say, 435 men and women, each elected to represent a single constituency, and they all get together to make laws. Now what?

Well, presumably, somebody has to be in charge.

Okay, but wait, slow down. What are the rules of voting here? And big question — what kind of powers does this leader get?

Okay, let’s stop here and think about the purpose of a legislature. The primary role of a legislature is to draft and vote on proposed laws.

The real question is what gets to come up for a vote, when, and how?

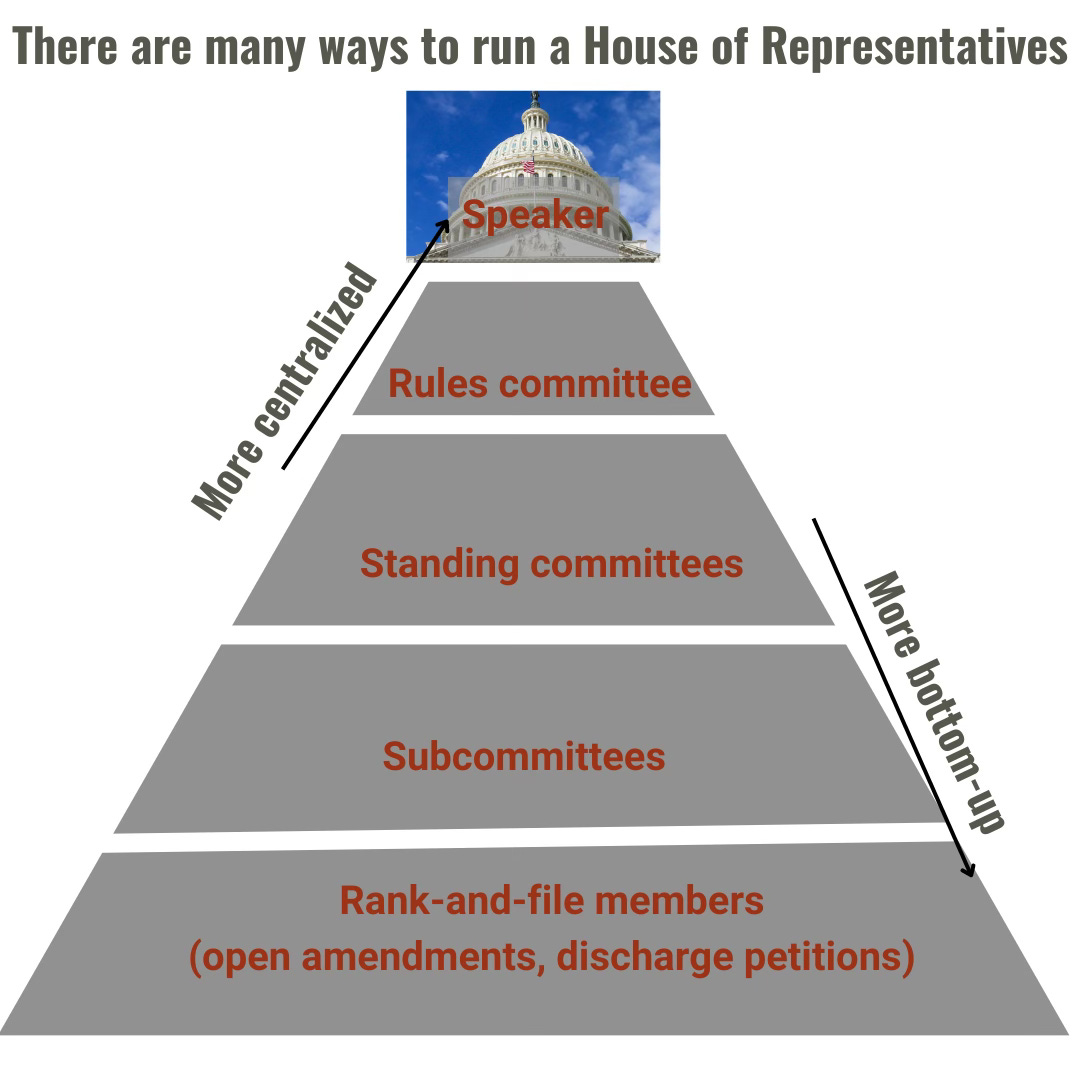

Throughout the history of Congress, there have been four basic ways in which this procedure has operated, which I’ll list here in pyramid-chart style — most top-down at the top, most bottom-up at the bottom.

The most centralized approach empowers the Speaker significantly to decide what bills come to the floor, when and how. This Speaker-centric model has dominated the US House for four decades now. Under this mode, the position of Speaker is tremendously important, because the Speaker basically runs the place. This mode was also used in the 1890s and 1900s. But it’s not the only way to do business!

A second approach is that a leadership committee runs the place, somewhat independently of the Speaker. The committee is also selected by the chamber. Typically this has been the Rules Committee. At certain times, the Rules Committee has had tremendous control, independent of the Speaker. The Rules Committee was independently powerful from 1937 to 1961. A committee can be more representative of the entire chamber, or at least a governing coalition, than a single person.

A third approach is individual standing committees operate independently. They can bring bills up for a vote after the bills have passed through a committee. When many commentators describe “regular order” this is what they have in mind. But really, this has not been a particularly regular mode of order in the US House. Perhaps the height of committee government was in the 1880s. Committees were also independently powerful for much of the 20th century, from the downfall of Speaker Cannon, up through the re-centralization of power in the Speaker. Multiple committees can be even more representative, but more diversity of perspective means more competition for floor time.

A fourth mode disperses power even more, by devolving it to subcommittees. This mode existed briefly following the expansion of subcommittees in 1973. This approach gives many members an opportunity to participate. But it created a more fragmented and chaotic floor.

A fifth approach circumvents the committee and leadership process entirely and empowers rank-and-file members. One mode of bottom-up organization is the “discharge petition.” Under this procedure members who gather enough signatures for a bill get to bring that bill to the floor. At various moments (notably 1923 and 1931), the House has agreed to liberal discharge petition rules, because progressive Republicans demanded it. Progressive Republicans held the balance of power in these moments. Another way rank-and-file members can participate is through floor amendments. If the Rules Committee allows bills to come to the floor under more open amendments. This is potentially the most chaotic and uncertain mode of governing.

These are not mutually exclusive modes. Sometimes multiple modes have existed simultaneously, though often in tension with each other. Basically, the history of U.S. House organization has been a multi-dimensional tug of war across different modes of organizing, based on the demands of competing coalitions.

Congress is a very dynamic institution. This is the lesson of history.

The simple history of Congress is this: Rules evolve. Coalitions shift. And as coalitions change, they reshape the rules. Reshaped rules, in turn, redefine coalition dynamics, through new procedural conflicts.

Elections also drive changes. When new majorities get elected, newly empowered factions demand rules changes. When liberals gained seats in Congress in elections like 1948, 1964, and 1974, they pushed rules changes that give liberals more power. When conservatives gained seats in 1950 and 1966, they undermined those changes. Earlier, when progressive insurgents held the balance of power in 1909, 1923, and 1931, they used their power to demand more access to the floor. When they no longer held the balance of power in 1911, 1925, and 1933, their procedural reforms were undone.

No arrangement is particularly stable. All arrangements have trade-offs. And all leadership arrangements contain the seeds of their own destruction. Giving one group power makes another group resentful.

In his excellent new book Why Congress?, the AEI political scientist Philip A. Wallach describes “The Pendulum of Congressional Organization.” The history of Congress involves oscillations from bottom-up openness and top-down tightness.

As Wallach writes,

“On the side of openness, too much manyness leads to an ineffectual scrum. In the ensuing cacophony, interests can opportunistically push policies that benefit themselves but are contrary to the public good. On the side of control, too much suppression of manyness leads to a stranglehold by one faction or an alliance of factions.”

Wallach argues that the swings of the pendulum tend to go far. “Eventually,” he writes, “the solutions to yesterday’s pathology become tomorrow’s problem to solve.”

Periods of centralized leadership can last until enough members get pissed off that they don’t have enough power. Then they revolt. Revolt, however, can cause chaos and disorganization, which creates demand for somebody to impose order.

Strong leadership solves a collective problem of organization and prioritization. But it requires a majority of members to agree how to organize and prioritize. This is the problem Republicans are experiencing right now. They don’t agree on what they want to empower a leader to do. But they want somebody to impose order.

In such eras of internal party dissensus, alternatives exist: Less centralized power, more leadership by committee, or by committees (plural). But these processes are less predictable, which is why members are not always comfortable with them.

More decentralization can allow for more flexible majorities across different issues (see, roughly 1973-1981). However, it poses challenges when there’s so much fragmentation, nobody can agree on anything. Some organization and structure is necessary to build governing majorities.

1789-1890: The early speakership, as if molded out of (Henry) Clay.

Enough theoretical throat-clearing. Time for the real history. Or rather, time for my abbreviated and stylized history of leadership and organization in the U.S. House of Representatives.1 (To any true Congress history buffs who may be reading, I apologize in advance for over-simplification. Truly detailed history > internet attention span.)

Gotta start with the Constitution. The Constitution says only that the House should “chuse” a Speaker (Article 1, Section 2, Clause 5). It lists no formal powers. Nor does it specify any method of “chusing.” And as many commentators have pointed out in teasing a Trump speakership, the Speaker does not even have to be a sitting member of the House.

Presumably, the Framers envisioned a model of the Speaker of the British House of Commons, who acted more as a presiding officer — tasked primarily with light administrative authority. The British Speaker still serves in this limited presiding officer role. The US speakership, by contrast, evolved into something much more powerful.

The very first Speaker of the House was Frederick Augustus Conrad Muhlenberg, of Pennsylvania. Perfectly affable gentleman, perhaps. But not a major historical figure. Mostly he sat by while James Madison dominated the First Congress, which contained a mere 65 members.

Hence, that classic rhyme about Muhlenberg’s mootness in the chamber:

Fred Augustus, God bless his red nose and fat head

Has little more influence than a Speaker of Lead

(Catchy, right?)

Manyhistorians describe the early batch of House speakers as largely ceremonial figures, though they increasingly entered the fray as time went by. Henry Clay gets the most credit for transforming the office during his speakership (1811-1825) through his impassioned speeches and partisan leadership.

But Clay was one of a kind. A known charmer, Clay once said, "Kissing is like the presidency, it is not to be sought and not to be declined." Clay never did get to be president. Alas.

After Clay, the speakership went back to being more marginal. As Congress and the nation developed in the 19th century, the committee system expanded to manage the expanding specialization and workload.

In 1885, the political scientist named Woodrow Wilson (yes, that Woodrow Wilson) wrote a book called Congressional Government. The memorable tl;dr one-line quote from the book was this: “Congress in its committee rooms is Congress at work.”

Wilson lamented a chaotic process, with the Speaker at the mercy of the committees. He wrote:

…there are as many Standing Committees as there are leading classes of legislation, . . . It is this multiplicity of leaders, this many-headed leadership, which makes the organization of the House too complex to afford uninformed people and unskilled observers any easy clue to its methods of rule.

1890-1910: The powerful speaker, v.1

Soon enough, however, Wilson’s then merely academic frustrations were OBE (Overtaken by Events). In 1890, Thomas Brackett Reed reinvented the speakership with the eponymous “Reed Rules” — a new top-down way of doing business in the chamber, in which the Speaker put an end to dilatory tactics and committee independence, and ran the chamber for Republican majority, and the Republican majority only. For this, he earned the nickname “Czar Reed.”

The era of a centralized speakership lasted two decades (with some intermissions). Reed’s successor as Republican speaker, Joseph Cannon, followed the czarlike approach to running the chamber. But Cannon pushed it to its limits.

1910: The revolt against Cannon ends the era of strong speakers

A 1908 political cartoon pictures Speaker Joe Cannon, recognizing a House of miniature versions of himself. It describes his centralized leadership style. Progressive Republicans seethed, organized, and deposed him of his power in 1910.

The downfall of Cannon demonstrates how things can and do change dramatically — at least when particular forces align.2

The basic story goes as follows: During the first decade of the 20th century, a growing progressive reform movement brought a new generation of Republicans into Congress. These new progressive Republicans didn’t like the way Cannon ran Congress and cut them out of the process. More specifically, these progressive Republicans were from farm states and had progressive-populist policy ideas. Cannon was very much opposed.

As they grew more and more frustrated with the ways in which Cannon abused his power to shut them out, they plotted their revolt. Through procedural cleverness, they eventually worked with Democrats to strip him of his power.

Some have reached back to 1910 in hopes of finding a parallel. Perhaps now, like then, an insurgent group of Republicans might work together to dethrone the powers of a dictatorial Speaker, and move away from the centralized leadership model.

Yet, the differences are significant. The insurgent progressive Republicans were extremely organized and unified, largely under the leadership of George Norris of Nebraska. They had also built relationships with Democrats, so there was some degree of trust. And, perhaps most importantly, the progressive insurgents believed in majority rule and had specific progressive policy proposals they thought could win majority support.

1911 - 1961: Leadership By Committee, Sort of, Mostly

Following the cannon revolt, Congress moved away from a strong speaker model, and towards more rule by committee. But the struggles of the 1920s and 1930s suggest different possibilities, depending on the extent to which organized factions play a pivotal “fulcrum” role.

In 1923, about 20 Progressive Republicans held the balance of power that year. By December of 1923, they were sick and tired of having their progressive legislation ignored by old-guard Republican leadership (which was still in charge). So, once again, they worked with Democrats. This time they passed a discharge petition rule. If a bill could get 150 signatures, it would have to come to the floor for a vote.

Again, this was a cross-partisan compromise, with a minority faction in the majority party (the Progressive Republicans), working with the minority party (the Democrats). Once again, the progressives were tightly organized, this time under the leadership of Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin.

In 1924, LaFollette ran for president as a Progressive Party candidate. He got 16.6 percent of the vote, and won his home state of Wisconsin. But Calvin Coolidge won in a landslide , and Republicans also piled up big majorities in the House.

In 1925, Republican speaker and Washington dandy Nicholas Longworth (of Ohio) re-centralized power in the speakership, but he worked closely with Democratic leader John Nance Garner, a conservative Texan, who shared many of Longworth’s conservative views. By working with Garner, Longworth was able to punish the progressive Republican insurgents. Garner later became FDR’s vice president from 1933-1941.

In 1931, the margins were extremely close. Republicans began the year with a narrow margin. But special elections shifted the balance of power. Once again, the narrow balance of power gave progressive insurgents the ability to demand a more liberal discharge petition rule. This time, they got the requirement for a vote down to 145 signatures (1/3 of the chamber).

But again, the narrow majority was short-lived. In 1933, Democrats won a landslide, and promptly held their majority for 56 of the next 60 years.

But after initial enthusiasm for the New Deal, conservatives in the Democratic coalition (mostly in the South) grew more skeptical, and returned to their more conservative roots. So, although Democrats had a majority in the House, conservatives effectively ran the place, through the conservative-dominated Rules Committee.

This balance reflected a kind of strategic detente. Democrats decided they’d rather maintain the majority than punish their conservatives. And conservative Republicans decided they’d rather wield power by working with conservative Democrats, rather than trying to sharpen the contrasts between the parties. So bipartisan governance was possible.

This arrangement lasted, in various forms, through the early 1960s. Between 1937 and 1961, the role of the House speaker was less dominant. The committees, assigned by seniority, largely controlled the chamber. The Rules Committee (run by a bipartisan conservative coalition) largely proscribed the limits of the possible.

However, in various moments, liberal Democrats had enough numbers to pass procedural rules to give their legislation a better shot. In 1949, more liberal Democrats successfully passed a “21-day rule” to find a way around the Rules Committee. The new rule prevented the Rules Committee from sitting on a bill for more than 21 days. In 1951, however, the 21-day rule was repealed, following Republican gains in 1950. This is yet another example of procedural ingenuity and dynamism.

1961 - 1979: Ascendant liberals transform the rules

In 1961, liberal Democrats were fed up with Howard W. “Judge” Smith, the conservative Virginian Democrat whose seniority earned him a top position on the Rules Committee. Smith leveraged his leadership role to either block civil rights legislation from reaching the floor or to weaken it when he couldn't block it.

At the urging of liberal Democrats, frustrated with Smith’s obstruction, the House voted to expand the rules committee from 12 to 15. The resolution carried, 217 to 212. In 1963, the change became permanent.

In 1965, liberal Democrats again succeeded in passing a “21-day rule” to get around the Rules Committee. In 1967, following Republican gains in 1966, the rule was repealed.

In 1973, ascendant liberal Democrats passed new transparency rules to open up committee meetings, on the theory these rules would put more pressure on stubborn senior committee chairs. Liberal Democrats also expanded subcommittees, giving junior members (mostly liberals) more opportunities. Floor activity expanded, individual entrepreneurship thrived. But so did fragmentation.3

1980-present: The swing back to centralization

In 1980, the Democratic House Speaker Tip O’Neill complained, ”You now have 158 House committees and subcommittees, each with a chairman…People are saying, we’ve gone too far; let’s retrench.”

And so, after an era of fragmentation and openness, O’Neill began to revitalize the speakership once again, and impose some order. Floor rules became more restrictive. And Republicans, who were used to at least getting a hearing for their ideas, began to seethe. So did some conservative Democrats, who suddenly found themselves on the outs.

Jim Wright followed O’Neill in 1987 and further centralized power in the Speaker’s office. But where Mr. Wright went wrong was violating ethics restrictions on speaking fees by instead demanding groups to buy bulk copies of his book, “Reflections of a Public Man.” The Wright scandal helped galvanize Republican opposition to Democratic leadership.

When Newt Gingrich ascended to the speakership in 1995, he further centralized power. He demanded party loyalty from committee chairs, taking the final blows to the old seniority system. He also cut staff for committees and centralized party communications strategy, nationalizing the media narratives, often around himself.

The U.S. House of Representatives is now more than four decades into an era of powerful speakerships, and three decades into an era of extremely powerful speakerships.

In the 1990s, political scientists engaged in considerable theorizing to explain this centralization of power.4 The consensus view was that the strong speakership was the logical extension of parties that were becoming more ideologically homogeneous, such that they were willing to delegate more power to a single leader because they largely agreed on what the party should prioritize. Another mainstream theory suggested that in eras of narrow partisan margins, members preferred a unified team approach, believing that sticking together helped their side win elections.

Of course, a strong top-down leadership has a reinforcing dynamic, a kind of doom loop quality (if you will). Powerful party leadership undercuts freelance bipartisanship among members. Powerful leadership raises the stakes of winning a majority, since top-down leadership means members of the minority party have much less to do other than plot their return to majority status. Both of these factors feed polarization. And polarization feeds the partisans’ demands to win and dominate. Which in turn drives the demand for stronger leadership.

As I wrote in The Atlantic:

This escalating partisan warfare, reinforced by a powerful House speaker, has in turn led to the rise of anti-system actors such as Gaetz. Under a strong speaker, members of the opposition fume, radicalize, and plot revenge until they can regain power to inflict partisan punishment. Such retribution requires a strong speaker of their own.

Which takes us to today….

Congress will have to change because it always does. The question is how.

If history is a guide, then the pendulum should swing back towards more decentralized leadership. The speakership will become a less valuable prize, and power will disperse into committees.

However, as I argued in a previous post, we are largely in uncharted territory. History is a limited guide to where we might be headed.

The closest parallel is 1910, when progressive insurgent Republicans stripped Speaker Joseph Cannon of his powers. But again, progressive insurgent Republicans of 1910 were an organized group, with clearer policy demands. They also believed in governing through majorities, and were frustrated that Cannon was thwarting progressive legislation they believed would get a majority vote if it were allowed to come to the floor.

Today’s far-right insurgents have no affirmative vision for what they want to accomplish. They have no policy proposals that could gain majority support in a more decentralized or open Congress. They are just angry and conflict-seeking.

It is certainly possible to imagine a group of moderate Republicans today banding together the way progressive Republicans did in 1910, and working with Democrats to re-organize the House. And the more far-right insurgents hold out, the more likely this becomes.

But the big difference today is that such moderate Republicans would put their re-election in deep jeopardy. They are scared of a primary challenge. And even if they survive a primary (which most incumbents do), they run the risk of a demobilized base in the general election. There are no single-winner districts where Moderate Republicans are a majority.

This is why I really do think it’s past time to consider proportional representation for the U.S. House, as Dustin Wahl and I wrote a few days ago in Time. In an electoral system with larger, proportional districts would allow more moderates to win seats in Congress, where they could work together to build governing coalitions. For example, in a seven-member district, the 15% of voters who want a Moderate Republican could elect their own.

A multiparty House would of course be different. But not that different. All governing involves building a majority coalition. The history of the US Congress is a history of evolving governing arrangements, based on ever-shifting partisan, ideological, and coalition dynamics.

The status quo is clearly broken. It’s time to use our imagination a little more. There are many ways to organize a legislature. And here, history provides insights

The history of the U.S. House of Representatives is a history of constant organizational change. Nothing stays the same. There are many different ways to organize a legislature.

Remember, you get a vote….

My primary resource for this history is Eric Schickler’s excellent book Disjointed Pluralism

Here, I rely on and recommend Ruth Bloch Rubin’s excellent academic journal article on the 1910 revolt, “Organizing for Insurgency: Intraparty Organization and the Development of the House Insurgency, 1908–1910”.

Julian Zelizer’s book On Capitol Hill: The Struggle to Reform Congress and Its Consequences, 1948-2000 is exceptionally good on the reform history.

For a helpful and sensible overview and synthesis, see Steven S. Smith’s academic journal article, “Positive Theories of Congressional Parties”

As the biggest Sam Rayburn fan, I feel obliged to let anyone reading this to check out the Hardemon/Bacon biography of the longest ever Speaker from Texas. It really adds beautiful color to the Speakership during the New Deal, WWII, and pre-Kennedy periods - especially in the famous final fight with Rules Chairman Smith.