The U.S. House has sailed into dangerously uncharted territory. There’s no going back.

Seven data points mapping the weirdness of this moment, and a plea for reform.

The US House is now in uncharted territory.

Yes, you probably know this from following the ongoing drama over the vacated House speakership. As of this writing, we are now 17 days into this manufactured crisis.

But how uncharted?

And if we’re off the map, where are we headed? And are we off to “There be dragons” land? (Possibly, yes)

In the pixels ahead, I’ll visually map where we are. As we’ll see, there are some historic parallels. But not enough to feel like we’ve really been here before.

Here’s what’s distinct about this moment, based on the best metrics we have.

Congress is more polarized than ever.

The Republican Party is more far-right than ever.

The share of House districts that are truly competitive is tinier than ever (less than 10 percent).

The share of House districts splitting their tickets hit a 100-year low in 2020 (fewer than 4 percent).

Partisan margins in the House are uniquely narrow.

The dimensionality of voting in the House has collapsed into a single dimension.

The Republican Party is growing more internally divided.

To close observers of politics, none of these findings may be that surprising. But I hope by seeing them all together, we can appreciate how unusual this moment is — and just how far we’ve sailed away from the “normal” patterns.

My simple takeaway is: We’re not going back.

So we need to ask: where do we want to head now?

If we are deliberate, we have possibilities. If we are not deliberate, the sea of dragons may chew us into pieces.

So come aboard. We’re going on a data journey.

(The data will cover only the U.S. House of Representatives. Similar patterns hold in the Senate, but since the House is in crisis right now, and the trends are clearer in the House, that is the focus of this piece, which is already long-ish)

Republicans have moved far to the right and polarization is at record highs

You have probably heard that polarization in Congress is high these days. It is. In fact, it is at a record-high.

Commonly, polarization is measured with “NOMINATE” scores. These are political science metrics that put roll-call votes into a giant algorithm. Then, based on who votes with whom and how often, it generates ratings on single score, from -1 to 1. This score is useful short-hand for a left-right dimension in Congress.1

So, let’s give a first look at where we are and where we’ve been. I start here post-Reconstruction, for continuity of parties. I plot the Democratic median in the House, the Republican median, and the chamber median (which combines all members)

Two takeaway points here:

First, the parties have never been super-close as measured by the distance of the medians. But they are clearly farther apart than ever.

Second, most of the change involves Republicans moving right since 1980, into uncharted territory.

The moderates have left the House

The lines above, however, only measure the median Republican and the median Democrat. That means that half of the Democrats would be on either side of that dot, and half of the Republicans would be on either side of that dot.

Since most governing gets done in the middle, we might want to see what the middle looks like. In the graph below, we are measuring only “moderates” — as defined here by a value of between -0.2 and 0.2 on this one-dimensional -1 to 1 scale.

Each dot represents a lawmaker in the U.S. House. From the 1930s through the 1990s, the political middle was a jumbled place. Both parties were more like loose overlapping coalitions. In many ways, Congress during this period operated more like a four-party system, with liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats, alongside liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans.

This overlap allowed for quite a bit of flexibility and fluidity in issue coalitions. During this period, the Speaker of the House was much less powerful than today. Power rested much more in individual committees.

Today, few members reside in the middle. Bipartisan compromise is rarer. The Speaker is a much more powerful actor, helping to keep parties aligned in unified opposition to each other.

Competitive congressional districts have largely disappeared

A second unique aspect of this moment is that competitive congressional districts have become exceedingly rare. In 2022, nine out of ten seats were essentially safe for one party or the other. This is both a driver and a consequence of polarization. Competitive districts pull individual members to seek votes from the opposite party, which tugs towards moderation and compromise. Safe seats do not.

Competitive seats have been steadily disappearing since 1998, when the Cook Political Report first began rating the competitiveness of House districts.

Gerrymandering often gets blamed for the disappearance of competitive districts. However, most of the blame goes to the geographic sorting of the two parties. Democrats and Republicans now live in very separate places. It is hard to draw competitive single-member districts when partisans live in geographically distinct places. (I have a whole big report on the challenges of districting, if you are looking for a deep dive)

Split-ticket congressional districts have also largely vanished

Another metric is the number of districts that different parties for president and for the House These are described as “split-ticket districts” (a throwback term from a time when voters handed in party tickets, and thus had to physically tear their tickets if they wanted to vote different parties for different offices).

The post-War period of common split-ticket voting reflects an era in which many voters were willing to vote for either party, and many even preferred divided government, with one party controlling the legislature, and the other in the executive office.

Some of this era’s incumbents were quite safe, but if they retired, the seat could flip.

What appears to be unique in this current post-2010 period is the extent to which so many individual states and districts are solidly partisan, while the country as a whole is evenly divided.

This suggests that the partisan balance of power will remain tight in Congress for the immediate future, even as most incumbent members are from extremely red or blue districts. And since tight margins and deeply divided parties make governance difficult, hold onto your masts. The sailing ahead is treacherous. We now turn to the narrow margins.

Partisan majorities in the House are unusually narrow

One reason Republicans are having such a hard time agreeing on a leader is because they have a very narrow majority. A narrow majority means that if they want to elect a partisan Speaker of the House, they need 99 percent support within their caucus. This narrow majority gives a small group tremendous leverage to make big demands.

The graph shows the partisan seat margin, with the curved brown line representing a smoothed rolling average. The current narrow majority is rarely charted territory. Usually majorities are much more comfortable.

The only other time the House was this evenly balanced was in 1931. Republicans began the session with a slight edge, but a few special elections went the Democrats’ way, and shifted the balance of power. But, given the difficulties navigating such narrow margins, an insurgent faction negotiated a very liberal discharge petition rule, such that if a bill got 145 signers, it could get to the floor for a vote. Of course, once Democrats got a big majority in 1933, they naturally raised the threshold for a discharge petition, and made such petitions more difficult to utilize.

Narrow majorities make partisan governing more difficult, but narrow majorities also tend to empower stronger leaders who solve the coordination problem among the narrow majority. After all: how do they stick together so they all benefit? However, they have to agree to empower a leader.

Dimensionality is collapsing upon us

Here we come to what presents to me as the most dangerous and unprecedented aspect of our current era — The Collapse of Dimensionality.

Ominous, right?

Let me explain what I mean by “collapse of dimensionality” and why it's a problem you should care about.

Let me try it this way: As you may be aware, we humans perceive a three-dimensional world, which gives us tremendous opportunities to navigate. But imagine if we lost a dimension and could only move on a flat surface? (you may recognize this as the premise of the novel Flatland). And what if we could only move in one dimension, say left or right? Well, then we’d all be one-dimensional characters — one of the sharpest insults a literary critic can foist on a novel. The basic idea here is that more dimensions makes the world a richer landscape of possibilities.

How does this apply to Congress? We know what a one-dimensional Congress looks like because that’s the one we see — the one dimension is left vs right, Democrats vs Republicans, us versus them.

What would a multidimensional Congress look like? At an extreme level of multidimensionality, we might think of each issue as a dimension. So, for example, gun policy and tax policy might be completely different issue dimensions, such that a member’s votes on gun policy might tell you nothing about that member’s votes on tax policy. Both might also be unrelated to foreign policy.

However, if every issue were its own dimension, chaos would reign. This is why political parties always emerge in legislatures — to help organize voting and provide some structure.

As a general rule, the number of issue dimensions in a legislature relates to the number of parties in a simple manner. Take the number of parties, and subtract one. That gives you the number of issue dimensions. So a pure two-party system would have one dimension. A three-party system might have two dimensions. A four-party system is three dimensional. It’s a rough calculation, and it depends on many other factors, but as a basic rule, the more parties, the more potential coalitions.

Of course, there are limits. Again, too many dimensions, and fragmentation becomes a problem. But in the middle space of three or four dimensions, systems seem to be the most robust.

The collapse of dimensionality reflects a loss of diversity. Diversity is necessary for creative problem solving. Without diversity of opinion and perspective, politics just a numbers game. No innovative coalition-building, no positive-sum re-framing — just a tug of war with a fraying old piece of rope.

This is why collapse of dimensionality is a problem in any complex system. And this is why the collapse of dimensionality is especially dangerous in a political system. Political polarization is the most obvious manifestation of the collapse of dimensionality.

Measuring the dimensionality of Congress essentially involves asking a question of roll call voting data: How well does the voting data fit a one-dimensional model? The liberal-conservative NOMINATE voting score we’ve been using throughout is a one-dimensional measure of voting. But in earlier periods in which Congress was less polarized, the one-dimensional model left much more out. Now it captures much more, at least at the voting level.

The graph below charts the uni-dimensionality of voting over the entire history of Congress. (Thanks to Jack Santucci for calculating this. He first posted about it on his blog)

With this measure, we are in especially uncharted territory. The one-dimensionality of congressional voting has waxed and waned. In certain moments (notably around 1820 and 1850) things became somewhat chaotic. In the 1970s, there was also a somewhat chaotic voting period. These have been eras in which existing coalitions were shifting. But never before has it been this one-dimensional.

In many complex systems, a collapse of dimensionality foreshadows a breakdown of the existing order. B It can reflect a transition moment. Again, we are in uncharted territory. We don’t know what happens when voting in Congress becomes this one-dimensional.

The last time voting in Congress approached this level of one-dimensionality was around 1910. In 1910, progressive Republican insurgents worked with Democrats to take power away from the extremely powerful speaker Joseph Cannon. In so doing, they set in motion a shift away from centralized power in Congress. Maybe something like this could happen again. But in 1910, progressive Republicans were a coherent organized faction, willing to partner with Democrats.

However, because this measure of one-dimensionality is only based on votes, it only reflects the dimensionality of voting on bills with recorded votes. This may seem obviously tautological. But as with any measure, what it may leave out is equally important to what it includes. And here, we are not seeing the conflicts over issues where votes are not recorded.

It is also possible what we are seeing in the data is a period in which party leaders are uniquely controlling the agenda. And they are only allowing votes on issues where the parties are unified in their opposition to each other. Thus, the one-dimensionality may merely be at the surface-level.

This takes us the fifth and final point — the tantalizing possibility of a Republican party split…

So, is the Republican Party about to crack up?

As anyone following Congress may have noticed, Republicans are in disarray. That disarray is now showing up in the data.

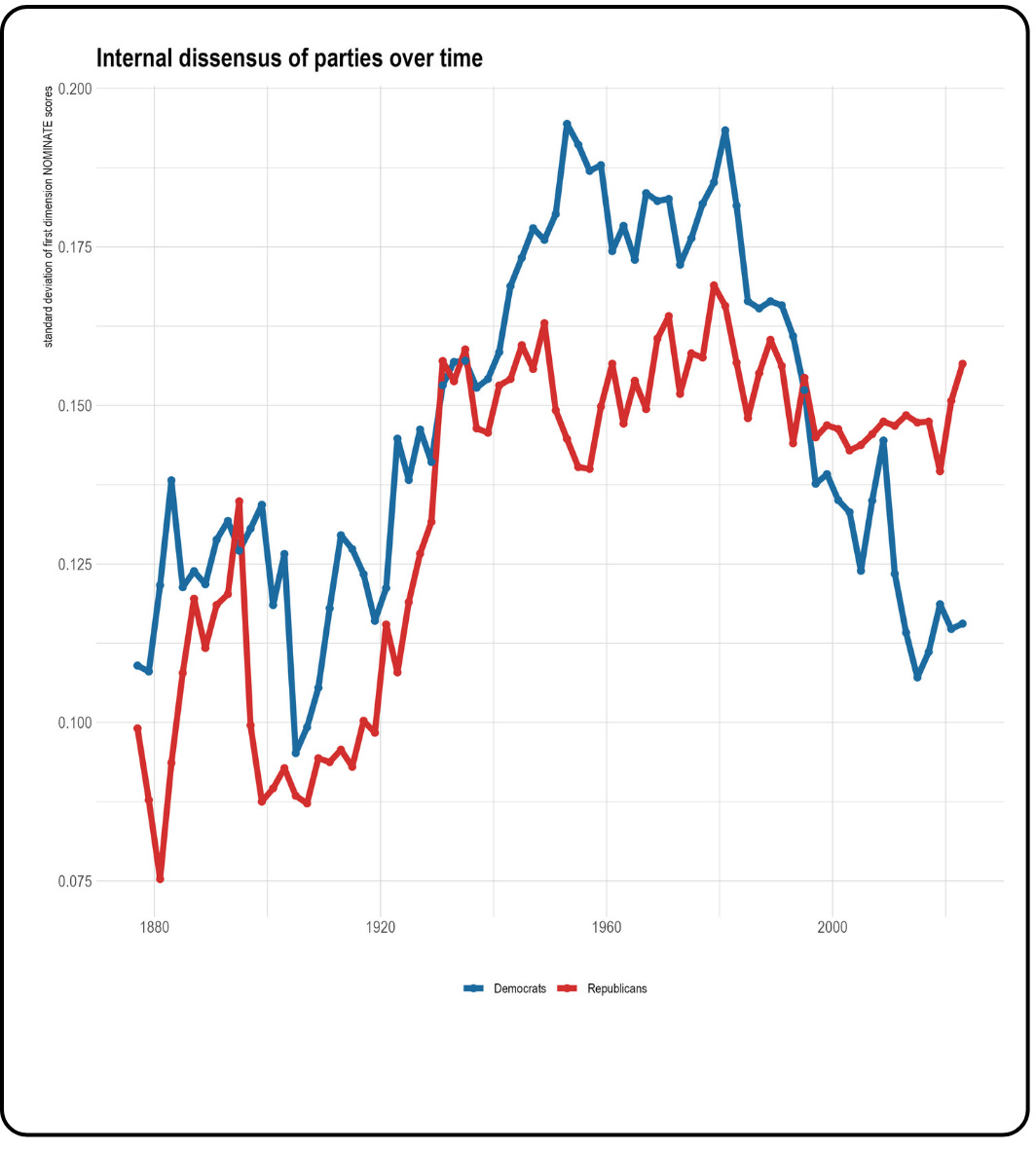

The measure here is the standard deviation of the first-dimension NOMINATE score. It is a way to measure the variability of scores among Republicans. And here, we see something … interesting. Variability (what I’ll call here “dissensus”) is increasing. Perhaps it’s not surprising, given what we’ve been seeing these last few weeks.

Notably, Democrats have been more unified of late. This shows up in the data. It also shows up in the stability of Democratic leadership in the House since Nancy Pelosi ascended to the Speakership in 2006.

I have one final graph, and it describes some very uncharted territory.

This graph shows the journey of the Republican Party along 2 dimensions — the left-right “ideology” dimension (as measured by the party median of the first-dimension NOMINATE score, plotted along the x-axis) and the unity-diversity dimension (the standard deviation, or variability, of the first-dimension NOMINATE score, plotted along the Y axis).

More specifically, it shows that the Republican Party is simultaneously far-right and internally split to an unprecedented degree. We have never been here before. And this seems like a particularly dangerous place for a party to be.

It’s possible this signals a Republican crack-up ahead. But absent changes to our electoral system, it’s really, really, really hard for meaningful new parties to form.

Uncharted Territory means we have to invent our own chart of the future

The hard thing about Uncharted Territory is that, being uncharted, it’s really hard to know how where we are headed.

Some aspects of the current moment reflect Rarely Charted Territory. For example, the contentious parallels of 1910 (when insurgent Republicans stripped Speaker Joseph Cannon of his powers) and 1931 (when an evenly divided Congress agreed on a liberal discharge petition rule). To the extent history offers parallels, the most likely outcome would be an end to the strong Speaker model of Congress, and a move back towards a more decentralized, committee-based organizational structure.

However, in those earlier periods, politics was less nationalized, and voting was less one-dimensional. There was still some play in the joints, some flexibility in the coalitions. Today, that seems much less likely. Too many of aspects of this current period are unprecedented.

From my readings into the dynamics of complex systems, the trends (particularly the collapse of dimensionality) suggest a system on the verge of a significant transformation. The current arrangements feel quite shaky because we are experiencing the tremors of an organizational arrangement that can no longer hold.

If we are truly in uncharted territory, the map of the past offers little advice.

It’s normal to fear the uncharted. This is our natural conservative instinct — however imperfect the status quo might be, it at least reflects the accumulated wisdom and traditions of years; most alternatives are likely worse.

But in this uncharted territory, we are beyond the accumulation of traditions. We are in the unknown, whether we like it or not. And all the signals suggest big change ahead. There is only one option: start thinking creatively about how we might govern ourselves in the years to come. The future, after all, belongs to those who show up with a plan.

Here, of course, is where I cue my song and dance about the need for electoral system reform to Break the Two-Party Doom Loop: Fusion voting and proportional representation, people. We’re in uncharted territory. It’s time to take alternatives seriously while we still have time to consider them.

Like all measures, NOMINATE has limits. One obvious limit is that it only measures votes, and votes do not always reveal true preferences since the set of questions on which votes get taken in Congress is but a subset of all relevant policy questions, and there are many reasons why people vote the way they do. But it is good enough to place us on the broad map of where we are and where we have been.

If you haven’t yet read Lee’s book on Break The Two-Party Doom Loop, please hasten to do so.

The one topic that Lee kept out of this excellent substack piece I would have liked to hear his opinion on, is the much more moderate GOP voting when a vote is by secret ballot. Far fewer Republicans supported Jim Jordon on secret ballot votes compared to roll call votes. How does that inform Lee’s perspective?

To what extent does fear of Trumpism cause some moderate Republicans to publicly vote one way, and another way when there vote is secret? Are Republicans- however intimidated by MAGA, actually more moderate that roll call votes would suggest?

How should we endeavor to define the terms "conservative" or "right?" It seems to me that the Republican Party has moved somewhere beyond the normative bounds of these terms and we do not yet have an understanding of what to call the territory it inhabits. Traditional conservatives would most likely not recognize the current Republican Party as "conservative" at all, since it is not trying to conserve anything, but rather to tear down.