Wither the Senate?

Thoughts and charts on the bias and legitimacy of America's distinctly malapportioned upper chamber

Control of the United States Senate is once more on the line this November. Democrats currently hold a narrow 51-49 majority, even though Democratic senators currently represent 58% of Americans1

But Democrats have to defend seven seats in close races (4 Lean D, all relatively populous: AZ, MI, PA, WI; and 3 Toss-Ups, only one relatively populous: MT, NV, OH), with no realistic pick-up opportunities. West Virginia (population: 1.8 M) is almost certainly a Republican pick-up.

Republicans have many ways to win a Senate majority without Republican senators representing a majority of Americans. Democrats have no way to win a Senate majority without representing an overwhelming majority of Americans.

Consider this: Even if Republicans win all seven of the contested races and catapult themselves to a 57-43 Senate majority, Democratic senators would still represent slightly more than 50% of Americans.2

The wildly malapportioned United States Senate has had a pro-Republican bias for four decades now. But in 2024, with our high-stakes, hyper-nationalized, hyper-polarized, doom loop politics, and a Republican Party that is lurching so far right that the entire left-right spectrum feels confused and inadequate, Senate malapportionment bias is more consequential than ever.

This essay is a deep dive on the costs and benefits of the Senate, circa 2024. It builds off an academic chapter I wrote for a newly-published edited volume, Disruption? The Senate During the Trump Era (Oxford University Press), edited by Sean M. Theriault. It’s a great volume, and I was delighted to be in the distinguished company of so many top-notch contributors. My chapter is called “The Crisis of Senate Legitimacy.” So, let’s talk about that crisis…

The wildly malapportioned Senate has a growing partisan bias

The United States is a very weird democracy, by comparative standards. And among our many odd quirks is our Senate: an upper chamber that is not only wildly disproportional (with the largest state roughly 67 times more populous than the smallest state), but also more powerful than the lower chamber (highly unusual).

Many modern democracies long ago curtailed the power of their upper chambers (who hears much about the House of Lords these days?), or just got rid of them entirely. Among contemporary democracies, the United States competes with Brazil and Argentina for the world’s most disproportionate upper chamber, and it probably stands alone as the most powerful upper chamber (In most democracies, the lower chamber has more formal power than the upper chamber. The United States is the exception. the Senate has more power, since it approves treaties and appointments that the House has no say on.)

The United States Senate has always been malapportioned, and as I document in my chapter, the relative small-state bias of the Senate has actually held pretty constant for much of the nation’s history. But what has changed is the partisan consequence of the small state bias. For the last four decades, the small state bias has consistently given Republicans more representation than population alone would command.

The chart below tracks the percentage of Americans who are represented by Republican senators alongside the percentage of senators who are Republican.

The only year in which Republican Senators are at the 50% mark is 1997-1998. (Well, technically, they’re at 50.2%, so yes, technically a majority. But barely). You have to go back to 1957-1958 to find Republicans representing a clear majority of the American population (52.5%). But even representing a minority of Americans, Republicans have regularly controlled a majority of Senate seats since 1981. Except for a few years in the 1950s, Democrats have never pulled off this feat.

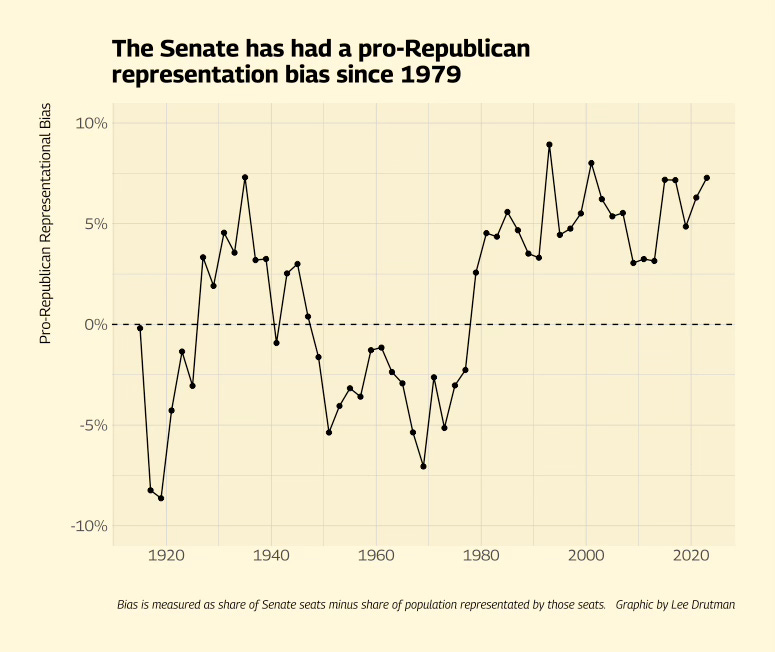

How big is the partisan bias? How has it changed over time? Our next chart measures this bias by calculating the share of Republicans in the Senate minus the share of Americans represented by Republican Senators. And that bias has consistently been about five percentage points pro-Republican since 1981.

Now, I will admit this is not a perfect measure. I’m counting the entire population of a state as Republican or Democrat for each Senator that represents the state, for purposes of this calculation. But yes, even in the most lopsidedly partisan states, about a quarter to a third of residents support the minority party.

It would indeed be fairer if the third of South Dakotas who vote for Democrats got a senator to represent them, alongside the third of Californias who vote for Republicans got a senator to represent them. But that is not the electoral system we use to elect senators, unfortunately. So yes, winner-take-all elections for the Senate distort accurate representation.

The countermajoritarianism consequences of partisan bias translate into real policy distortions

How does this representational bias translate into legislative outcomes?

Here, I want to highlight two recent academic articles.

The first, just out in the American Political Science Review (the flagship political science journal), is simply titled, “Senate Countermajoritarianism,” by C. Lawrence Evans. It’s the most comprehensive analysis to date of the countermajoritarian bias of the Senate, covering the entire history of the country. (Steven S. Smith has a helpful summary of the article in his substack)

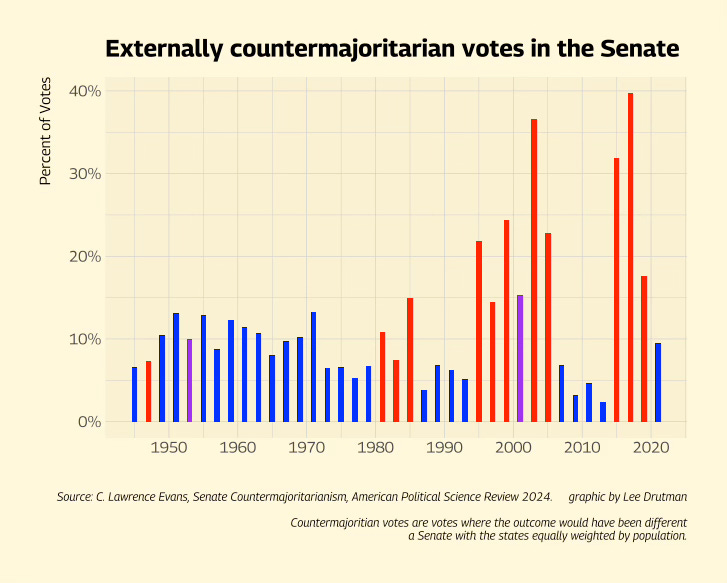

One useful measure is the share of votes that are what Evans calls “Externally countermajoritarian” — that is, the outcome of the vote would have been different in a Senate where states are equally weighted by population.3

Externally countermajoritarian votes have been uniquely high in recent years under Republican control. In two periods with unified Republican control (2003-2004) and (2017-2018), the share of countermajoritarian votes in the Senate was almost 40%. Or put another way, a significant share of legislation that passed under Republican majorities might not have passed had the Senate been weighted by population.

Richard Johnson and Lisa L. Miller focus more narrowly on key initiatives under presidents in their recent paper, "The Conservative Policy Bias of US Senate Malapportionment.” And, they find more evidence that Republicans are the big winners from a malapportioned Senate.

For example, 12 major bills passed under Trump would have failed in a perfectly proportional Senate. By contrast, seven major bills that failed under Obama would have passed in a proportional Senate.

Policywise, reversals were most common on gun control, abortion rights, and healthcare issues. Civil rights and immigration reversals were also very common.

These re-weighting analyses don’t account for the potential filibuster. Senators have used the filibuster much more widely during the last few decades, shaping the agenda. And presumably, in this alternative world of a proportional Senate, the political agendas would have been different. Still, these analyses give us some sense of the consequences of Senate countermajoritarianism.

The small-state Senate bias is also a white bias

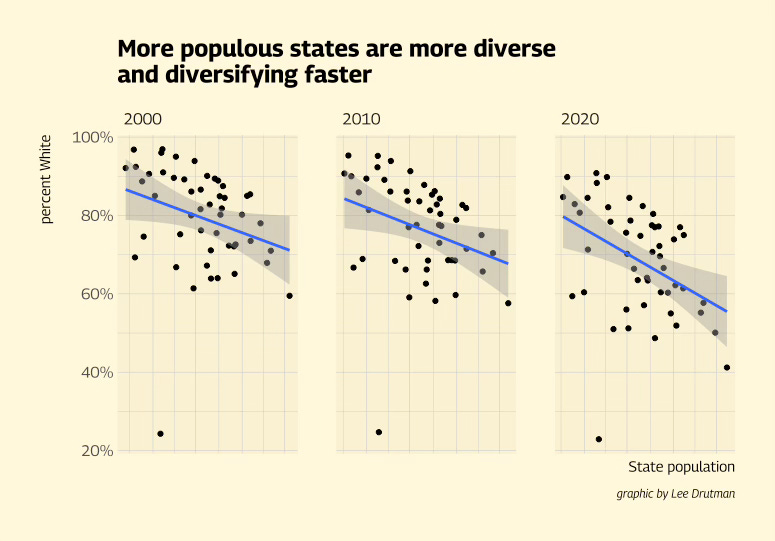

Regardless of the partisan bias, there is also a demographic bias to the small state bias. Small states are less diverse than large states. And large states are diversifying faster.

As I note in my chapter:

Over the last two decades, as America has become increasingly racially diverse, much of that diversification has happened in more populous states. Less populous states have always been more White than more populous states, but that trend has accelerated over the last two decades. Thus, the Senate not only overrepresents Republican voters over Democratic voters; it also overrepresents White voters over voters of color (see Figure 11.4).

Demographers expect that as America becomes more diverse over the next several decades, more populous states will diversify faster. These trends will exacerbate the White-state bias of the Senate over time, thus adding another dimension to the potential legitimacy crisis of the Senate as unrepresentative of the United States population as a whole.

What is the purpose of the Senate? Why bicameralism at all?

As I argue in my chapter, all this countermajoritarianism and bias and malapportionment are creating the conditions for a legitimacy crisis. When political institutions fail to represent a majority for decades, that starts to become a legitimacy crisis.

Now, no governing institution is perfectly fair, and from time to time, some modest countermajoritarianism can provide important institutional checks against excessive populism. There are reasonable arguments in favor of our Senate.

For example, one can argue: Well, sure, the Senate has some biases. But…

1) there are maybe some good reasons for a second chamber different from the first that represents states equally (like say, a “sober second thought” and protecting federalism; and

2) Maybe those biases are just contingent on the current partisan-demographic-geographic-coalitional political alignment now, but might not be permanent, and therefore, let’s not let our democratic fairness outrage-o-meter get out of control!

PLUS: What are you going to do, change the Constitution?

Perhaps the Senate is valuable because it offers a “sober second thought”?

Why bicameralism at all? Let me quote myself, from my book chapter:

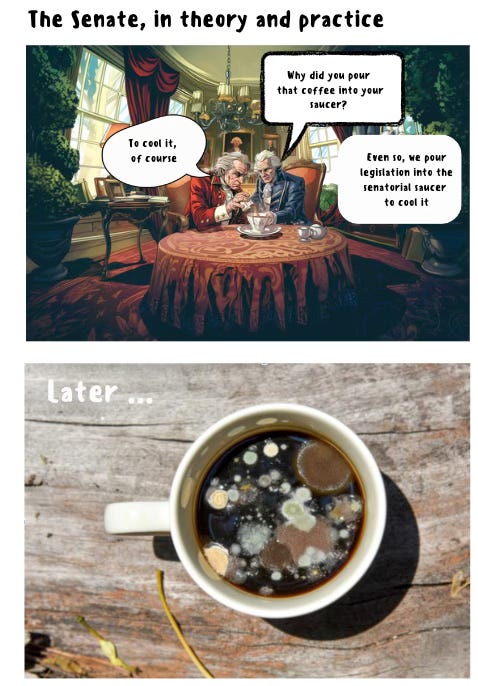

Every advanced student of American government knows the apocryphal story in which Virginians George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were discussing the purpose of the Senate while drinking coffee (or perhaps tea). “Why did you pour that coffee into your saucer,” Washington asked Jefferson. “To cool it, of course,” replied Jefferson. “Even so,” Washington said, “We pour legislation into the senatorial saucer to cool it.” Apocryphal or not, it does capture one widespread rationale for bicameralism (particularly at the time).

Essentially, the generalized case for bicameralism suggests two main benefits: A “sober second thought” (that the Senate can offer a strategic pause on the sometimes over-heated passing passions of the lower House) and a “second opinion” (that the Senate not only offers a pause, but also a different way of looking at things which comes from its ability to provide a new and different perspective).

As an aside here: as somebody who drinks A LOT of coffee, I have never once poured my coffee into a saucer to cool it. Sometimes if my coffee is very hot, I will wait a little bit. Occasionally, I’ll add some cool water (But rarely milk. I prefer my coffee black as a penguin’s tuxedo). But I’m not George Washington.

Of course, I agree that deliberation and debate are indeed valuable when it comes to legislating public policy for an entire nation. But to take the imperfect analogy one step further, it’s one thing to let the legislative coffee cool a little. It’s another thing to pour it into a saucer, and leave it in the cloakroom where it festers for months and develops a weird mold before some hapless page has to dump it out.

Again, I can see the purpose of bicameralism – if a second chamber considers the first chamber’s work a solid first draft, and then improves on it to pass something better (as sometimes does happen). But finding that right balance invites a paradox attributed to the Abbé de Sieyes: “If a second chamber dissents from the first, it is mischievous; if it agrees it is superfluous.”

Now, I’ve heard the argument that perhaps when the country is deeply divided, it is better for the federal government not to act. So let me quote my chapter again, responding to this argument.

Perhaps the Senate should prevent a narrow and quite likely fleeting majority from forcing its preferred policies on the rest of the country. Perhaps it is better to let the individual states make policy in most areas. Perhaps only if and when there is broad national agreement, only then should Congress legislate.

Perhaps. The consequence of Congress failing to resolve issues over the last two decades is that states have reinforced the national divides by moving in decidedly different policy directions. Over the last several decades, gridlock in Congress has corresponded to increased policy divergence in the states. Put simply, Republican-controlled states are passing extremely conservative policies; Democratic-controlled states are passing extremely liberal policies. These divergences both reflect and reinforce existing national level polarization. Congressional gridlock, driven largely by a filibuster-happy counter-majoritarian Senate, has not fostered compromise. It has just transferred partisan warfare to the states.

If the Senate is supposed to be the deliberative, reasoned institution, then the current moment of hyper-partisan conflict would be precisely the moment in which a second chamber could add the most value by offering an entirely different perspective on existing partisan conflicts. Indeed, this is the key selling point of a second chamber—that it offers not only sober reflection, but also a new angle through a process of deliberation.

So, if the Senate is not forging compromise, but instead just reifying and deepening existing national divisions, then, again: what purpose does it serve?

Of course, as an observer of Congress, I do observe that the House passes quite a bit of deeply unserious legislation that is just messaging. So it is no great tragedy if the Senate politely ignores them often.

But House majorities often pass these ridiculous bills precisely because they know the Senate will kill them. Presumably, if the United States moved towards a more limited role for the Senate, two things would happen: 1) Being a senator would be less desirable, and so the most talented and ambitious politicians would stay in the House, instead of trying to be become Senators; and 2) Leaders in the House would take their responsibilities more seriously and not pass reckless legislation because they would actually have to face the consequences of it.

Almost certainly, a more serious and representative House would require eliminating single-member districts and enacting proportional representation. And Certainly, it would take some time to reach a new equilibrium. But as long as the Senate exists as a “sober second thought,” the House can get away with being deeply unserious on many occasions. Which creates its own obvious problems.

Perhaps the Senate is valuable because it protects federalism and small states?

A second argument I often hear in favor of the Senate is that the Senate is the guarantor of federalism. This claim is particularly common among conservatives.4

But there is no evidence that the Senate is a defender of federalism. Absolutely none. Zero. Zilch.

If the Senate were a defender of federalism, on issues of federalism, we would expect to see that the Senate and the House vote differently, with the Senate more on the side of states’ rights, and the House more on the side of the federal government.

But that is not what anybody who has looked at this rigorously has found. What studies do find is “fair-weather federalism” — when a Democrat is in the White House, Republicans in both the House and the Senate support more state-level autonomy, at equal rates. When a Republican is in the White House, Democrats support more state-level autonomy. But there are no differences between the Senate and the House on issues of federalism.

But what about big states dominating small states? Are there any issues in which small states and large states are currently at odds? Have there ever been? Wyoming and California may be different, but when do small states and large states line up on different sides of a national policy question?

I have not found any modern issues where small states and big states systematically disagree, either in the House or the Senate. Nor has any one else studying the issue5

Again, partisanship explains much. State population or size explains little.

Now, we can debate the merits of federalism separately. I see some value in devolving more power to local political units. Though as political units, states feel increasingly antiquated altogether. The divides within states, between urban and rural areas, are far wider these days than the divides between states. If we are going to take the idea of federalism seriously, we need to take the idea of localism seriously, too. And we should also discuss the arbitrary nature of state boundaries, while we are at it.

It is conceivable in theory that a second chamber could specifically represent state interests and the principle of federalism, not partisan interests. But in practice, it hasn’t. When Democrats have unified government, Democratic Senators are happy to empower the federal government. When Republicans have unified government, Republican senators are equally delighted to give the federal government power. Fairweather federalism, indeed.

Okay, sure the Senate benefits Republicans in a countermajoritarian way NOW, but it hasn’t always...Right???

Not so long ago, the entire Senate Delegation from the Dakotas was Democratic. From January 3, 1997 through January 3, 2005, both Senators from South Dakota were Democrats. From January 3, 1987 through January 3, 2011, both Senators from North Dakota were Democrats.

Now both of these states seem so deeply Republican that it is hard to imagine a Democrat ever winning again. But, of course, things can change.

Indeed, as Evans concludes in his “Senate Countermajoritarianism” article, “Based on demographic and political projections, Senate countermajoritarianism is likely to grow more entrenched in the years ahead, further fueling the widespread skepticism that exists about the legitimacy of the chamber. Yet, as we have seen, the magnitude and impact should vary in ways that reflect the political configurations of the day.”

The United States party system has always changed, and always will. Internal migration could change these states and other low population, currently very Republican states — and with it, the partisan bias of the Senate. This is possible. Perhaps liberals will flee big liberal coastal cities where the cost of living is too high for potential new hubs in Boise (ID), Bozeman (MT), and Cheyenne (WY). It really wouldn’t take that many transplants to change the partisan balance of these states. Perhaps some mega-rich liberal who cares deeply about climate might fund this internal migration?

Of course, such machinations of internal migration might sound very silly. But our national representative institutions all use majoritarian winner-take-all elections, which has a very perverse unintended consequence — these types of elections make outcomes highly sensitive to the distribution of partisan voters across electoral boundaries.

The same national population can yield very different outcomes depending on how voters sort into states along party lines. This is the same reason why single-winner districts are so vulnerable to gerrymandering. With gerrymandering, it is the lines that shift to yield different results holding citizen residence constant. (For a deeper dive into the problems of fairness inherent in single-winner elections, see my essay here on House elections and districting.)

This inherent unfairness, of course, is the problem that proportional representation solves so elegantly, by making boundaries much less consequential for electoral outcomes. With proportional representation, you get the same outcomes regardless of electoral boundaries and internal population migration.

But while proportional representation is a natural fit for most of the elections to the U.S. House of Representation, Senate elections are all single-winner elections. Certainly, there are options to improve single-winner elections, such as fusion voting, which would give more parties a role in forming coalitions around individual Senators.

Perhaps a different party system would soften any partisan bias of the Senate, or at least make it less predictable from election to election. But still, unless state population is uncorrelated with other important dimensions of representation, the Senate will still have a distinct bias.

Well, complain all you want… The Senate is in the Constitution.

Yes, the Senate is in the Constitution. Once upon a time, the original 13 states were separate colonial territories, though with the same colonial overlord and the same language (though with some different types of settlers). They did come together as independent states to form the United States. As the United States expanded westward, territories became states.

In other federal nations, like Germany or Switzerland or India, the distinct states within the nation reflect genuinely distinct cultures and often languages, with long histories of independent development. Many were independent states first. Not so in the United States, where many of our individual states were actually creations of the nation, and the boundaries and populations often reflected partisan calculus.

Adding states has long been a partisan game. From 1864-1890 Republicans worked very hard to “stack” the Senate through tactical state admission, starting with Nevada in 1864 (population of just 6,857(!) in the 1860 census), Nebraska (1867), Colorado (1876), and then the piece de resistance — the 1889 omnibus that admitted North and South Dakota as separate states, along with Montana and Washington. The 1890 admission of Idaho and Wyoming followed. Ever wonder why there is a West Virginia? It was originally part of Virginia, but when Virginia seceded from the Union in 1861, the western counties resisted, and formed their own state in 1863 – which Southern states weren’t around to object to!

Could the western territories have been split differently to make different states? Absolutely! Did the choice of state boundaries have consequences for the balance of power in the Senate? Absolutely!

Here’s the simple point: The borders of the existing states do not reflect some natural property of state-ness. They are creatures of politics. If Democrats were to grant statehood to Washington, DC (as they absolutely should!), this would well be within the American tradition! Or, why not split California into three states to give Democrats four more Senators?

Or heck, what about counties? Just as a thought experiment, imagine this: Any county in the United States that has more people than the smallest state should have the option to secede from its current state, and form its own independent state, with two Senators in the United States Senate.

By my count, there are 115 counties in the United States with more residents than the entire state of Wyoming, the least populous state at 584,057 (as of July 1, 2023). At #115 is Douglas County, Nebraska, which contains the city of Omaha. It has slightly more people than the entire state of Wyoming. At #16 on the list is Bexar County, Texas, home of San Antonio, with just over two million residents, making it larger than the entire state of Nebraska (just under two million residents).

The most populous county is Los Angeles County, with almost 10 million people. If it were its own state, it would be the 11th largest state in the nation, just ahead of New Jersey, and just behind Michigan. There are currently 48 counties with at least 1 million residents in the United States. That’s more than the number of states with over 1 million people.

This is not a realistic proposal (I can already see many problems with it, not least of which is the obvious political infeasibility). But I raise this idea merely as a thought experiment to ask a simple question: if the purpose of having distinct states is to represent distinct political units with distinct values and perspectives, why not adjust the boundaries to reflect actual political communities with more shared fates and shared values?

And if the purpose of the Senate is to give these distinct political communities equal representation in the national government, why not revise these state boundaries to reflect the actual political communities as they exist today, and have developed over many decades?

Okay, but we’re not really going to abolish the Senate, are we? No, but how about a less powerful Senate in exchange for clearer rules around federalism and localism?

In the early days of representative democracy, both in the United States, and around the world, bicameralism was a transitional stage from oligarchy to democracy. The theory went something like this: A lower chamber, a people’s house, would be limited by an upper chamber, which would reflect the better classes. Thus, most upper chambers were appointed, while lower chambers were elected. Upper chambers gave the upper class elites a veto over too much democracy.

But over time, as representative democracy became more representative, some countries moved more towards unicameralism — one legislative chamber — by eliminating the upper chamber altogether. Other countries limited the role of upper chambers. For example, the United Kingdom still has a House of Lords. But for more than a century, its role has been extremely circumscribed. All the important action takes place in the House of Commons.

Again, The United States is globally unique in giving more power to the upper chamber than the lower chamber. The Senate has distinct powers that the House does not have, over judicial and political appointments, and foreign treaties. In no other modern democracy does the upper chamber have more power than the lower chamber, though some have the same power.

So, could we conceive of a less powerful Senate? In researching my chapter in Disruption?, I learned about recent upper chamber reform in Germany, which is also a federal nation. The reform was essentially a bargain: a less powerful Senate in exchange for more federalism. Here’s a slightly more detailed explanation (from my chapter):

Germany’s upper chamber, the Bundestrat, represents German states (Lander). Under the 1948 German constitution (which Americans helped to draft), the Bundestrat was given more limited powers. At the time, it was expected that only 10 percent of federal laws would require Bundestrat approval. By the late 1990s, the Bundestrat had claimed jurisdiction over much more legislation and had become an obstructionist body as the relationship between state and national authorities grew entangled. Germans increasingly blamed high unemployment, low growth, and growing budget deficits on the bicameral gridlock (Stecker 2016). But because of the complexity of the legislative process, German voters didn’t know who to blame or hold accountable. In 2003, Germany set out to form a “Joint Commission on the Modernization of the Federal State.” The commission laid out reforms that drew clearer distinctions between federal and state authority, and in exchange, reduced the power of the Bundestrat to only legislation that mandates specific implementation instructions. By most accounts, the reform appears to have been moderately successful — at least in reducing the ability of the Bundestrat to stonewall legislation (Stecker 2015; Zolnhofer 2008)

Federalism in the United States as of today is an absolute mess. But if conservatives are indeed sincere in their beliefs that more authority should exist at lower levels of government, and that localism and subsidiary are indeed important principles, then perhaps some kind of grand bargain does exist — a more limited role for the Senate, in exchange for more autonomy for local government units.

I would be wary of too much state autonomy, because many states are deeply culturally and economically divided internally. It doesn’t make sense to let California be California when different regions of the state have very different values and lifestyles (SoCal is different from NoCal is different from the Inland Empire), or to let Tennessee be Tennessee when Nashville and Memphis have different values and lifestyles from the more rural parts of the state. Letting coherent regions be themselves does make some sense. But drawing boundaries may be tricky. No lines are perfect.

Should a deal be struck, perhaps a less powerful Senate could focus mostly on foreign policy and long-term policy planning. It already has unique powers on foreign treaties, which perhaps it should retain. But in most areas of domestic policy, it should defer to the House.

Here’s another idea: The Senate could have a veto on domestic policy, but only if 60 percent of senators oppose the proposal. A kind of filibuster in reverse: Put the onus on 60 to oppose legislation, as opposed to support legislation.

The Senate once adjusted to the threat of illegitimacy. The 17th Amendment required senators to be directly elected, instead of appointed, giving the patrician institution a new jolt of democratic legitimacy. The amendment passed under the threat of a Constitutional convention, and at the height of the Progressive Era of democracy reform.

Will history repeat itself? Or at least rhyme? All governments depend on legitimacy to hold power in the long run. The costs of maintaining illegitimate institutions can be extremely destructive to a society. We’d all be better off averting the chaos and conflict illegitimate institutions of power too often create. I do not mean to sound radical or alarmist. But history is full of these lessons.

In the meantime, let’s start thinking creatively about what kind of bicameral future makes sense for the United States. I write only to stimulate conversation.

Assuming each Senator represents one half of the state population, 191.1 million Americans, while Republican senators represent 136.8 million Americans.

By my calculations, Democrats would represent more people (164.3 million) than Republican senators (163.6 million).

Evans defines it this way: “For the purposes of analysis, then, a roll call can be characterized as externally countermajoritarian if (1) the yeas outnumbered the nays, but the nays represented a larger share of the population, or (2) the nays equal or exceeded the yeas, but the yeas covered a larger portion of the American people. More concretely, for each roll call cast by a member, I assign to that individual one-half of the state population at the time.”)

Here, for example is the conservative legal scholar Richard F. Duncan: “the Constitution creates the Senate to check national power and to advance federalism by ensuring that each state in the union has an equal voice in one branch of the national govern- ment. . . . Each Senator elected to represent Wyoming in the Senate is a resident of Wyoming and was elected by the people of Wyoming. Thus, she is more likely to reflect the regional and cultural values of her electorate—the people of Wyoming—than would be the case if Senators were elected by a national electorate . . . Thus, rather than contradict the fundamental values of the American Constitution, the Senate’s embrace of federalism and state equality in one house of Congress reflects and embodies the checks and balances that protect the liberty of we the people of the several states.”)

See Eg., Frances E. Lee and Bruce I. Oppenheimer, Sizing Up the Senate, 1999; Also, John D. Griffin, “Senate Apportionment as a Source of Political Inequality.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 31, no. 3 (2006): 405–32. https://doi.org/10.3162/036298006X201869.)

By the way, I feel the need to point out that whether the Senate is all that biased depends on how you count. The median Cook PVI of the Senate is R+2. In other words, to hold the Senate, they just need to win the popular vote 51%–49%.

I think that bears repeating. If our voting system satisfied the median voter theorem (i.e. we had Condorcet, score, or approval voting), the median Senator would represent the 51st percentile of voters by conservatism, whereas under a perfectly well-apportioned system, they would represent the 50th percentile of the voters.

The Senate is, technically, biased towards Republicans, and this is stupid. But the only reason this tiny bias matters at all is the extremism forced on us by plurality-runoff. IRV/RCV and plurality-with-primaries both tend to produce winners from roughly the 25th and 75th percentiles, so that bias makes us swing from the 51st percentile all the way over to the 75th.

A fantastic article.