The Surprisingly Predictable Reason Why Trump Nostalgia Is On the Rise

Memory plays deceptive (and sometimes dangerous) tricks on us. Yet arguing with people’s memories seldom succeeds.

It makes no sense. When Donald Trump left the White House in 2021, only 41 percent of Americans considered his presidency a success. Now, three years later, that number has jumped to 55 percent.

It’s the same presidency! What gives?

Well… time. And memory.

Memory is a strange thing. We remember the past as better than it was. This is a well-documented cognitive bias called nostalgia bias.

And Trump is not unique in getting a nostalgia bump. Most presidents see their approval ratings go up after they leave office. But not all: Richard Nixon and Lyndon Johnson, both of whom left the White House under dark clouds, did not benefit from nostalgia. Trump left the White House under dark clouds as well, and threatens an even bigger storm of chaos upon return.

Can roughly one in seven Americans really have changed their mind about the Trump presidency? Can he really be benefitting from such a big nostalgia bump? What’s going on here?

Well, come along. We’re going to take a deep dive into the strange world of nostalgia and memory, and how it shapes our politics.

“Memory is like a record store. It stocks the hits of the past, and the hits as well as the stinkers of the present.”

In March 1939, the Gallup Poll asked respondents the following question: Do you think Americans were happier and more contented during the horse-and-buggy days than they are now? A large majority of (63%) believed people were happier and more contented back then. Only 27% disagreed.

But Gallup also asked : "Do you think you would have rather lived during the horse-and-buggy days instead of now?” Only 25% wanted to return, while 70% said they did not actually want to go back in time.

That was 1939, of course. A lot has changed since then. But our brains have not. We still tend to romanticize the past as more idyllic, particularly the era in which we grew up. (Even if we don’t necessarily wish to return to it exactly).

This bias emerges from how we encode memories. Mostly, we hold onto the pleasant memories, and let the bad ones fall away.

Perhaps this is because we like re-living our happiest moments, especially with friends and family. Perhaps we are bolstering our own self-esteem — we like to be the hero of our own story, and so revel in our successes, whatever they may be. Perhaps it is because when difficulties and disappointments are resolved, we no longer want to revisit them; Time heals most wounds.

Theories vary. But whatever the reason, our memories of the past are mostly positive. Thus, when we think back to the old days, most of us, mostly, recall the good. And we mistake our biased memories as representative, when they are highly selective.

Memory is like a record store: “It stocks the hits of the past, and the hits as well as the stinkers of the present.” The old days were full of stinkers, too. It’s just nobody replays the stinkers.

We’re always a little dissatisfied with the present, and a little nostalgic for the past. In most elections, the opposition calls for a return to the past, when it was in charge. During the Trump years, Obama nostalgia was a real thing.

In more normal times, this would all be fine. Nostalgia bias would just be a normal aspect of thermostatic politics — the predictable pattern by which public opinion turns against the party in power and its policies.

Rotation in power is important in democratic politics. If one side gets locked out for a long time, it can view itself as a permanent minority and question the legitimacy of the entire system.

Regular rotation in power between left and right keeps a healthy back and forth between more conservative, tradition-oriented approaches to governing, and more future-oriented, progressive approaches to governing. Both perspectives have their value, but balance is crucial. Left unchecked, both perspectives can spiral into absurdism. If conservatism is too prone to nostalgia bias, progressivism is too prone to optimism bias (thinking we can do more than we can).

Optimism bias is a different issue. It’s not the problem in this election or right now. My focus here is on nostalgia bias in politics.

Making America Great Again: today’s pathological version of nostalgia

Today, the nostalgia problem in our politics goes deeper than just people misremembering the past. We now have a dominant faction of one of our two parties devoted to a pathological version of nostalgia.

“We are a nation in decline, a failing nation” Trump likes to tell his audiences. “Make America Great Again” is a slogan of nostalgia (and a vague one at that — it specifies neither a time nor a circumstance of greatness.)

Nostalgia is a common response to uncertainty and unease. Citizens feeling uncertain and uneasy turn their minds to what they perceive as happier times, in the past. Politicians who promise to restore “the good old days” resonate with this nostalgia impulse. These politicians also emphasize the current decline and chaos. Change threatens some people. Under threatening change, some people seek refuge in nostalgia.

This MAGA-morphisis of politics is not uniquely American. Collective nostalgia is a defining feature of many populist right parties today. Marine Le Pen has promised to “Remettre la France en ordre” (restore order in France). The UK Independence Party promised to “Take Back Control of Our Country.”

Indeed, the prevailing sense of social pessimism and collective nostalgia is common among supporters of right-wing populist parties throughout the West. Supporters of such parties often feel like they have lost status. They are uneasy with the changes they see around them.

Some nostalgia can offer a useful coping mechanism in times of uncertainty. In many circumstances, it is perfectly benign — a normal, even healthy emotion. It helps people maintain a sense of identity and connectedness amidst uncertainty. It gives them grounding in a shared past. In its more benign form, nostalgia can “provide comfort, reassurance, and a sense of meaning.”

But unmoored, and unbalanced, nostalgia can take on darker forms. One of my favorite novels from the last few years is a strange book called Time Shelter, by Georgi Gospodinov (it won the 2023 International Booker Prize). The book starts with a “clinic for the past,” in which Alzheimer’s patients can inhabit rooms fitted with the emblematic furniture and accouterments of their preferred decade. Eventually, entire nations vote to inhabit the past. The novel is a dark comedy, of course.

In real life, the promise to restore national greatness is a frequent hallmark of fascism. In his 2004 book, the Anatomy of Fascism, Robert Paxton defined fascism as “a form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.”1

Fascism requires more than an obsession with decline. But it starts from this sense of decline. And the illusion of decline is real and persistent. For as far back as we have polling, polls consistently find widespread belief that morality, honesty, civility, and hard work were better in the past. A recent comprehensive academic analysis looks at 70 years of opinion polling across 60 countries and found that perception of moral decline was ubiquitous and constant.

And yet, the authors (Adam Mastroianni and Daniel Gilbert) found NO evidence that morality has actually declined. Not only was the perception of decline “pervasive and perdurable” it was also “unfounded and easily produced.” In fact, if anything, morality may be improving over time: “On average, modern humans treat each other far better than their forebears ever did—which is not what one would expect if honesty, kindness, niceness and goodness had been decreasing steadily, year after year, for millennia.”

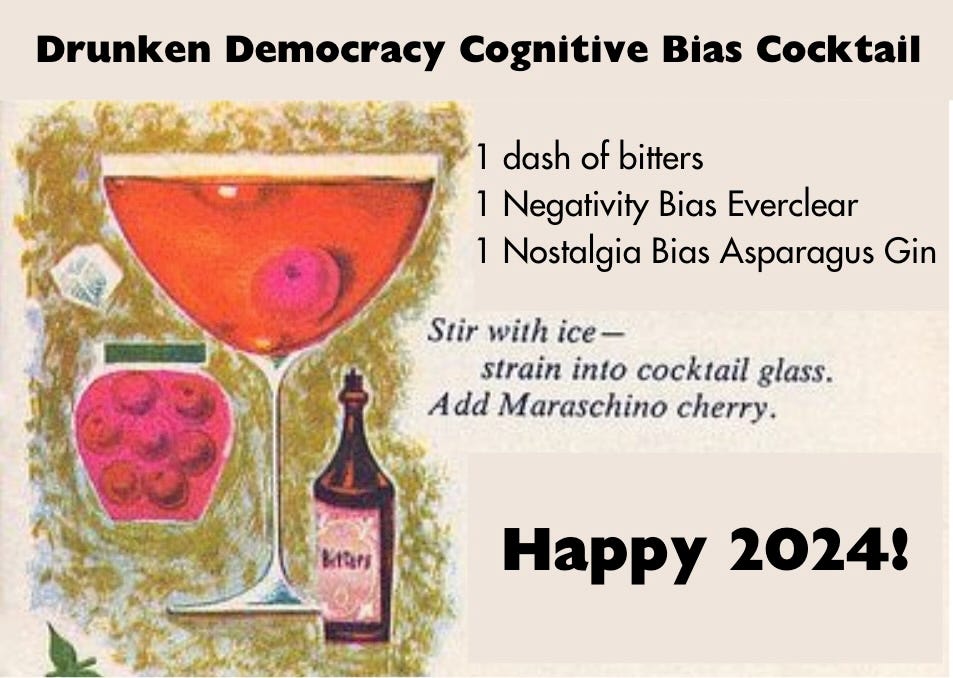

So why do so many people always mistakenly believe we are in moral decline The study argues this is because most people 1) remember the past as better than it was (nostalgia bias); and 2) experience the present as worse than it really is (negativity bias).

I haven’t said much about negativity bias yet in this essay. My previous essay here was a deep dive on negativity bias, and how our contemporary political-media environment has kicked this bias into dangerous overdrive. The quick summary is that our brains are deeply attuned to possible threats, and so we have a strong negativity bias in how we process the present. In an environment of nonstop national media and hyper-partisan confrontational politics, we are constantly getting triggered. This makes us especially likely to see the present moment as a crisis.

Thus, our overactive negativity bias towards the present (exacerbated by the hyper-partisan Battle Royale politics and always-on news) makes us all especially dissatisfied with our current politics; it helps explain our present anti-system moment — and why all our national politicians and institutions are viewed unfavorably.

And when we combine our deep dissatisfaction with the present with our tendency for nostalgia towards the past, the cognitive bias cocktail is especially potent.

And what about 2024? It’s hard to sell the status quo to an uneasy nation

At this point, you might be thinking to yourself: all this is very bad for 2024. And you’d be right.

Here, I’ll quote an interview from a recent New York Times piece interviewing some of the 14% (!) of Biden 2020 voters who said they weren’t voting for Biden again in 2024.

“All of our core values are gone, gone, and I’m just not pleased at all,” said Amelia Earwood, 47, a safety trainer at the U.S. Postal Service in Georgia. She believes the American political and economic systems need to be torn down…. She called Mr. Trump “a horrible human being,” but added, “I’m voting on his policies, and I think that he could straighten this country out, while Biden made a ginormous mess out of it.”

This quote nicely encapsulates the problem of nostalgia bias (for the past) and negativity bias (for the present).

If I had a conversation with Amelia, I really don’t know what I’d tell her. Or how I’d change her mind.

Would I explain that her thinking that “all our core values are gone, gone” was just the predictable illusion of moral decline? Would I painstakingly explain that Biden had not made a “ginormous” mess? Or at the very least, that the ginormous mess runs much deeper than any president? I don’t think that conversation would go well.

Amelia, like most Americans, feels extremely frustrated with the status quo. And I don’t blame her, entirely. I’d like to see big changes too! It’s just that I know that, despite my frustrations, keeping the status quo in power is better than the alternative on offer. But that’s not a very satisfying response.

In 2020, Biden benefited from nostalgia bias (towards the past) and negativity bias (towards the present). Trump’s transgressions were front and center. Trump was the president, and occupied center stage. Americans were dissatisfied (as they have been for a long time).

In 2020, Biden was the change. Biden was also the nostalgia: He had been in the White House four years back, when Obama (now benefiting from nostalgia bias as well) had been president. In 2020, Biden’s approval rating was positive, and above 50%. It had ripened since Biden was last in the spotlight — his approval rating while serving as Obama’s VP was mostly in the 40s, as was Obama’s.

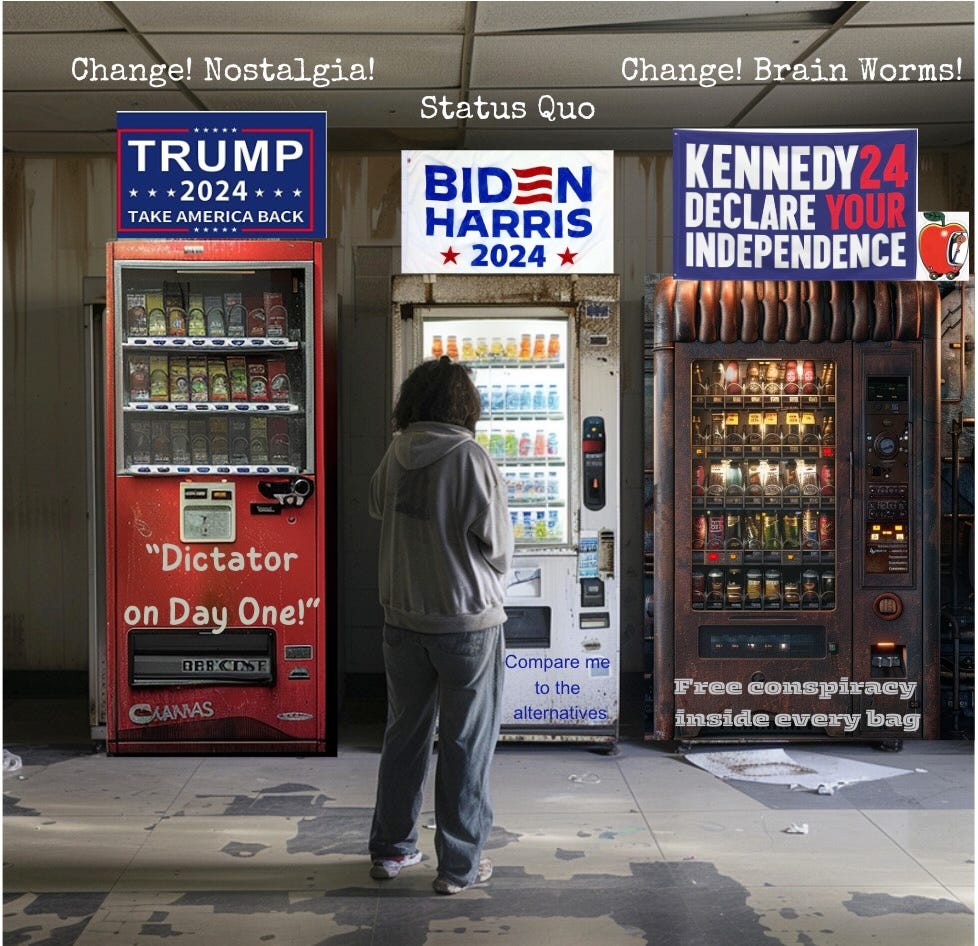

Now, in 2024, Trump is the change. Trump is also the nostalgia. That’s a problem for Biden and the Democrats. Some people who supported Biden in 2020 have indeed forgotten how much they disliked Trump.

I suppose if I were running the Biden campaign, I’d be putting together clip reels of the worst moments of Trump’s first administration, trying to remind people of all the things they didn’t like about him then, helping to reactivate the negative feelings people felt at the time. I gather this is the main campaign strategy, spiced with fear about an even more radical second Trump term.

But I have two worries about this strategy. The first is simply that it won’t work. Too many people just won’t remember the first Trump term as a nonstop crisis, particularly the pivotal “shrug emoji” voters who are mostly just disengaged, and might respond: “you keep telling us this is the end of democracy, but Trump was president once, and we still have a democracy, don’t we? Aren’t you just crying wolf?”

The second worry is that it actually does work, but it just further escalates the doom loop scorched-earth election negativity that is driving our politics into anti-system nihilism, in which we keep picking the lesser and lesser of the two evils until we have lost collective faith in the process of electoral democracy, at which point… who knows?

Either way, Biden benefited in 2020 from being the change candidate for a dissatisfied electorate. He cannot claim that “change” mantle anymore. Of course, it will be a close election no matter what, because the 80-95% of the electorate (depending on who actually turns out) is deeply partisan and thus deeply predictable. Almost everyone who voted for Trump in 2020 is going to vote for him in 2024, and most of these people are nostalgic for Trump in the White House already, and think his presidency was successful.

So we are really only speculating on a small share of the electorate. But that small share is pivotal in our knife’s edge politics, even if they are the most detached and poorly informed group of voters. They are also the most likely to want “change” and be perpetually dissatisfied with the status quo.

Pathological nostalgia is a long-term problem. We need a long-term solution.

I’m feeling pretty pessimistic about 2024 at this point. But I do like to end with at least a few suggestions for democratic improvement.

So, for the longer term, here goes…

Nostalgia appears to be a basic human emotion. Some nostalgia bias is inevitable in how we see the world, and maybe even beneficial because it does connect us to our past. It grounds our identity in social connectedness and tradition in ways that combat anomie and isolation.

So it’s going to be with us no matter what, and will probably increase, especially as our population ages. Already, we are seeing books of contemporary cultural criticism like “Retrotopia” and “Retromania”

Thus, the crucial question is not: how can we get people to remember the past more accurately? The question should be: how can the political system be resilient to some mis-remembering and nostalgia?

Certainly, nostalgia and social pessimism are widespread throughout western democracies. But, interestingly, in more proportional European party systems, a major distinction between supporters of far-right populists from the supporters of mainstream right parties is this sense of social pessimism and thus nostalgia. Though they often share similar issue positions, supporters of populist right parties are more nostalgic; they are more likely to long for an imagined past, and more likely to see the present darkly.

Because my refrain is electoral system change, I am obligated to tap my sign, and note that more and better political parties could help make our politics more resilient to pathological versions of nostalgia

In the United States, with our two-party system, the revanchist nostalgic movement has taken over one of the two dominant parties. So, to the extent that voters are registering frustration with the status quo this election, they only have one option right now for “change.” And to the extent those on the political right want a party that roughly shares their policy priorities and values, they only have a revanchist, increasingly illiberal party to support and identify with. Or the crazy brain worms candidate. If people want change (and this seems to be an electoral refrain), revanchist illiberalism shouldn’t be the only version of change on offer

We also need an optimistic, hopeful version of the future — a new “change we can believe in.” The alternative to social pessimism is not to “stay the course” or to convince people why their cognitive biases are leading them astray. The alternative is to tap into our optimism bias (more on this in the future), and give people who are disaffected from politics something to feel excited and hopeful about. This is a hard one for the Biden campaign to do (given its central protagonist), though perhaps a signature big hairy goal (like cutting poverty in half in ten years, or going all electric in a decade), could at least act as an inspirational north star. A simple, concrete goal does wonders for motivation. Optimism bias sometimes leads us astray, but it is also responsible for tremendous improvements in the quality of life over many centuries.

We can also deploy nostalgia as an emotional call for graciousness and innovation, tapping into the deeper story of American progress (Obama was particularly effective at this).

Of course, this is also a bigger societal problem (much as I love to throw my electoral systems reform hammer at any problem). To the extent that we understand what triggers a refuge to excessive nostalgia among some — and it seems to be some combination of uncertainty, loneliness, loss of status, rapid societal change — we might think about how to mitigate some of these triggers, within reason.

We also need to think more about how we engage an aging population in meaningful, community-oriented activities, rather than letting them feed and deepen their frustrations in the isolated televised irradiation of right-wing propaganda. (How we treat the elderly in America is another topic, but our inadequate investments in eldercare are a real tragedy.)

As with all cognitive biases, the most direct way to combat a bias is to acknowledge it. Explaining how predictable cognitive biases (like nostalgia bias) might lead us astray at least makes us question our thinking a little bit — which is good, now and then. But uncomfortable, too.

I don’t hold out much hope here, of course. This kind of disciplined meta-cognition is a pretty elitist project. But at least elites, particularly those in the media, should understand how and why nostalgia can distort our memories and perceptions, so we can be aware of it in our own analysis and writing.

These are not easy problems to solve. But simply telling people their memories are wrong is not a winning strategy. We need to do better.

page 218

“ A simple concrete goal does wonders for motivation ”

Please look at campaign finance vouchers (democracy dollars). As described in my essays, especially the latest one, it can be the motivator we need.

But it needs boosters to persuade the democrats to look up and consider the alternatives.

A story: my coworker was a dive bomber trainer. He tells of having to knock the controls away from trainees who were so focused on hitting the target that they were ignoring the need to pull out of the dive before crashing.

Our current democrat crew have lived in the fund raising focus so long (with disastrous results for 80% of the population, including the 2008 crisis) that the cannot look around and “pull out of their dive.”

We are in extreme danger of another 2008 banking collapse over commercial real estate. Warning signs everywhere. Not a peep out of Biden. Another one will kill us.

The answers to those two Gallup Poll questions in 1939 aren't actually contradictory and so don't require the bias explanation you provide here. In addition, the response that they wouldn't want to live in the horse-and-buggy-days seems inconsistent with the main tenets of your (interesting) piece.