The state of our democracy is cracking and evaporating

A guide to the thermodynamics of our constitutional crisis. And how to phase change out of it.

(This is the second in an ongoing series of posts reiterating the case for proportional representation – here is the first)

Welcome to the are-we-in-a-constitutional-crisis-probably-we-are-in-a-crisis times. It's all very strange. It’s hard to believe a phase shift like this could actually happen. Then bam. Suddenly we're here.

For several years I've been screaming about the two-party doom loop, and how it erodes the basic foundations of representative liberal democracy. For years I've been saying there is no return to normal. In a politics of hyper-partisanship, where "winning" is everything, anything goes. Norms break down. I also warned that while our politics might seem stuck, change might happen suddenly.

And... so… here we are. This is now a new state of American politics, cracking and evaporating all at once. We are going through a phase change.

To get out of this destructive state, we are going to need some pretty big changes in our political system. To understand why, we’ve got a lot to cover.

Here’s a quick preview:

First, we'll look at how political systems actually work - they're living things, really, that need the right balance of stability and change to stay healthy.

Then we’ll explore the thermodynamics of politics, and dive into some history to explain more.

Finally, we'll examine what all this tells us about fixing our system today through proportional representation.

So grab a big mug of coffee (or something stronger - these are constitutional crisis times after all), and let's dig in. We've got some big ideas to discuss.

The political system is a system. Systems have complex dynamic properties.

Probably the biggest challenge in understanding politics is appreciating just how thoroughly everything affects everything else. A kind of thermodynamics operates here — all actions have reactions; everything feeds back on itself. Over time, systems tend towards chaos, unless actively reformed.

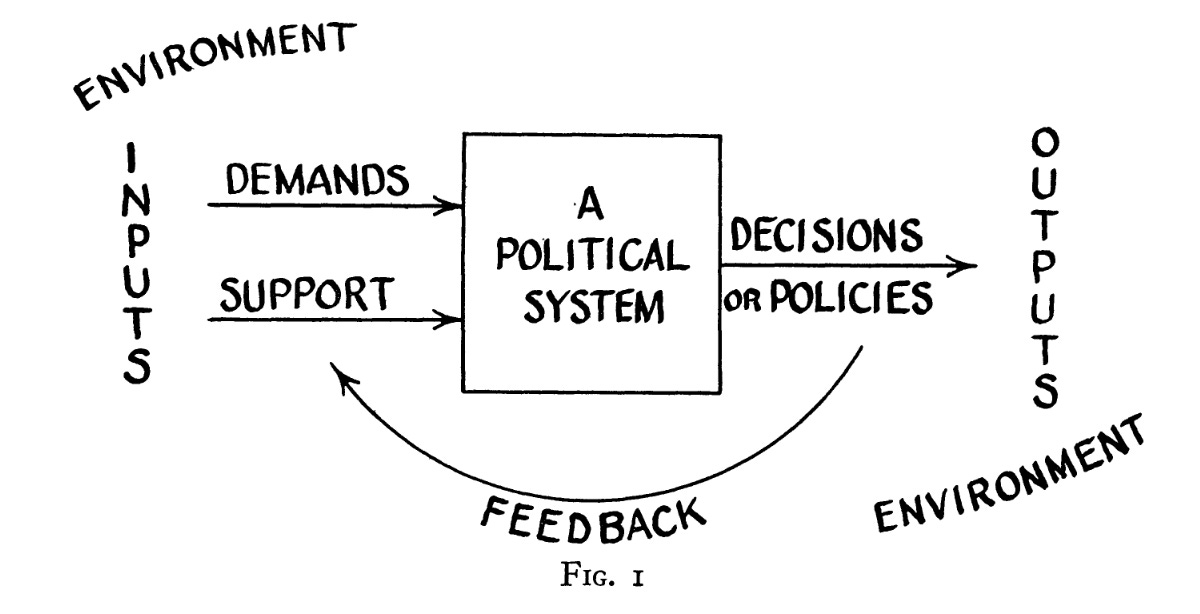

Complex systems can get very complex, so let's try to keep it simple. Let’s start with David Easton's classic 1957 model from "An Approach to the Analysis of Political Systems." Easton presented a "primitive model" of this system (his term). Below is Easton’s original sketch.

The core concept is simple: feedback drives the system. The policy outputs of a political system feeds back on itself, while the environment simultaneously generates new problems for the political system to solve. This is all pretty obvious when you stop and think about it. But sometimes a simple model is good for clarifying the obvious.

Take a simple example of how a feedback process might work: Imagine a government decides to deport large numbers of migrant workers. Because many farms depend on immigrant labor, food prices rise. These outputs now change the demands on the system. Before, a primary demand was to reduce illegal immigration. Now a primary demand is to reduce high prices. Perhaps the government then tries to impose price controls. But these reduce supply and create shortages, creating further anger.

The key point is that the political system is constantly evolving and changing. What happens in politics today shapes tomorrow’s political landscape. For every action, there is a reaction.

A political system remains healthy and stable to the extent that it can resolve the problems thrown upon it. It must also maintain broad public trust in order to effectively solve future problems. The system maintains its legitimacy by resolving problems in a manner that most people consider fair, or at least fair enough.

But if the system loses that trust, it limits the room to respond flexibly to demands. These failures further erode support and cause even more demands to accumulate. Eventually this "doom loop" will undermine the entire system.

Obviously, this is over-simplified (as all models are). But as a first approximation, it captures the key point: there is no equilibrium. Everything feeds back on itself.

Easton would expand on this model considerably in later works. Other scholars would as well. Self-reinforcing loops and dynamic change theories gained popularity in social sciences during the 1950s and 1960s. These theories emerged from the cybernetic paradigm that explored how complex systems work and self-regulate—or fail to do so.

That paradigm largely faded in the 1970s when micro-theories of individual behavior replaced macro-theories of complex interacting dynamics. But for understanding our current crisis, these big-picture models are exactly what we need. These models explain why our political system appears both frozen and chaotic simultaneously. They also suggest that changing fundamental rules might be our best hope for breaking destructive feedback loops.

In modern democracies, parties serve as the main channels through which citizens make demands on the system. But what happens when there are only two parties? As we'll see next, our two-party system creates its own dangerous feedback loops – ones that amplify conflict while preventing real change.

Parties are the crucial pipes of democracy that channel demands and connect citizens and government.

The simplified Easton model implies an unmediated relationship between demands, support, and the political system. But in modern representative democracy, these relationships are heavily filtered through political parties. Parties function as a plumbing system that channels demands into government action. They determine which issues demand attention, and what solutions get proposed.

Without functional parties, as without working plumbing, sh*t goes everywhere.

Parties select, amplify, and frame amorphous public demands to win elections Citizens express demands through the available parties. Most citizens decide what's important based on the discourse from politicians and partisan-aligned media. Elections are when the most people pay the most attention. Thus, partisan-electoral competition serves as the primary learning moment of modern democracy.

In a healthy system, competition can drive policy innovation and responsiveness. But in our hyper-polarized two-party system, it has turned toxic. In a rigid polarized two-party system, citizens seeking “change” (seemingly the one constant demand in politics) have constrained choices. For many loyal partisans, voting the alternative is unthinkable. But voting the same way is dispiriting.

Frustration kicks in when the system gets stuck. Parties escalate conflict to keep attracting voters. More frustration leads to more extreme positions, which creates more gridlock, which generates more frustration. This is the bad kind of feedback. This is doom loop feedback.

Let me modify the Easton model by visualizing political demands flowing through a system with a control mechanism that directs how these demands are channeled.

Pull the lever toward fewer parties, and citizens channel their frustration into pushing existing parties to fight harder. Pull it completely to two parties (as in our system), and political energy transforms into pure binary conflict. But pull that same lever toward multiple parties, and identical demands can flow into diverse political alternatives

The US party system's lever is currently locked at just two parties, the extreme end of the fewer parties direction – creating intense pressure for change that conflicts with the calcification.

But here’s the problem: When people want change but only have two options, they don't stop wanting change. They just push those two options to more combative stances. Parties respond by deepening the conflict.

This dynamic explains our current crisis: our system fails to constructively channel desires for change. Instead it amplifies conflict.

The states of democracy — frozen, gaseous, and fluid (fluid is the best; the other two are actually terrible)

Political systems, like H2O, exist in different states. These states of matter—frozen, gaseous, and fluid—correspond to three distinct political conditions.

The Frozen State: Like ice crystals locked in rigid formation, our current two-party system has crystallized into immobility. Our rigid two-party system becomes brittle when voter demands go unaddressed, risking sudden fracture instead of gradual adaptation. More ominously, authoritarian leaders can increase this rigidity by suppressing dissent, further freezing the political system.

The Gaseous State: This represents political chaos. Like molecules breaking free from all bonds, excessive fragmentation prevents stable governance. Weak institutions and inconsistent policies create an environment where effective governance becomes impossible

The Fluid State: This represents healthy democracy. Like water molecules, political parties form and break connections while maintaining overall system cohesion. The system's flexibility allows it to absorb shocks through structured but dynamic competition. Multiple political dimensions prevent any single fracture from splitting the system. In the 1960s, for example, the system proved flexible enough to absorb the tremendous pressure for racial justice while maintaining fundamental stability. Cross-party coalitions of Northern Democrats and Republicans came together to pass landmark civil rights legislation

Right now, the United States sits at the boundaries of frozen and gaseous. It’s a dangerous place to be.

So how does a political system move between these states? It depends on how the system manages and channels the demands.

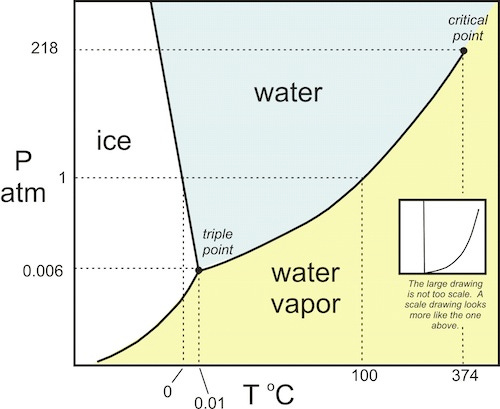

So, a quick lesson in basic thermodynamics. We know that water boils at 212°F. But go 3,000 feet up into mountains, where atmospheric pressure is lower, water boils at just 206°F. Conversely, in a sealed pressure cooker, water boils at higher temperatures (around 250°F), which accelerates cooking.

Here’s a basic temperature-pressure diagram for H₂O (“P atm” is atmospheric pressure):

In politics, electoral volatility acts like temperature – measuring how freely voters shift allegiances between elections. Higher volatility typically correlates with more parties, just as higher temperatures increase molecular motion.

Institutional constraints function like pressure. High-constraint systems feature strong democratic norms: clear boundaries of acceptable behavior, mutual respect between parties, and adherence to both letter and spirit of constitutional principles. As these constraints weaken through escalating norm violations, we enter the dangerous territory of "anything goes" politics – exactly what we're seeing today.

Here’s my states-of-political-matter graphic:

This framework helps us understand why our system needs reform and how proportional representation could provide both stability and flexibility. But first, a little history to illustrate the framework.

Lessons from the Civil War: When binary politics becomes explosive

The lead-up to the U.S. Civil War stands as a cautionary tale here.

For decades, the two-party system had managed sectional conflicts by accommodating diverse viewpoints. However, as North and South developed increasingly antagonistic values around slavery, this equilibrium shattered. The brittle political system faced mounting pressure from economic changes, territorial expansion, and growing moral opposition to slavery.

Though most Southerners did not own slaves, and the slave economy benefited only a small percentage of wealthy oligarchs, the binary political system enabled these Southern elites to rally their fellow citizens against perceived Northern threats. Conspiracy theories flourished. As Calhoun observed, Southerners became convinced that "Every portion of the North entertains views more or less hostile to slavery," while Northerners feared a "Slave Power" plot against free institutions.

The political breakdown manifested physically in Congress, where representatives began arriving armed, culminating in Preston Brooks's near-fatal caning of Charles Sumner on the Senate floor. The essential premise of democratic politics—that each party views the other as a legitimate alternative government—collapsed along with the party system. When Lincoln won the four-party election of 1860 with only 39 percent of the popular vote, Southern states responded by seceding.

In this binary conflict, Southern identity became inseparable from slaveholding. . As the historian David Blight wrote in a recent New York Times essay titled “Was the Civil War Inevitable?":. “In a two-party system, the capture of one party by extremists is enough to cause great political havoc and violence — a lesson we should have learned from the destruction of our Union in 1861”

The Progressive Era breakthrough: Releasing pressure through multiple channels

The Progressive Era offers a more encouraging example of how frozen politics might re-liquify rather than explode. [FN: This capsule summary of the Progressive Era recapitulates what I wrote in my 2022 white paper, "How Democracies Revive," published with the Niskanen Center: https://www.niskanencenter.org/how-democracies-revive/]

Through the 1880s and into the early 1890s, two-party competition remained closely balanced and voting loyalties ran deep, similar to today's calcified politics. However, multiple pressures were building: rapid industrialization created new urban-rural tensions, waves of immigration reshaped demographics, and economic upheaval generated both labor militancy and agrarian protest.

The Panic of 1893 exposed the brittleness of existing political arrangements. The People's Party (Populists) emerged as a powerful third force, winning several western states and forcing both major parties to address monetary policy and economic reform. Labor conflict intensified, exemplified by the Pullman Strike of 1894, while agrarian unrest took shape through the Farmers' Alliances.

Crucially, these pressures didn't align along a single axis. Unlike the sectional crisis of the 1850s, new cross-cutting divisions emerged: East versus West on monetary policy, urban versus rural on economic questions, and native-born versus immigrant on cultural issues. This multidimensional stress prevented the system from fracturing along any single fault line. Instead, like water molecules gaining energy, political alignments became more fluid and dynamic.

Unlike today's rigid duopoly, the system had what engineers might call "play in the joints"—flexibility that allowed for adaptation rather than catastrophic failure. The Populists, despite their ultimate electoral defeat, demonstrated how third parties could introduce new ideas into the political ecosystem without destroying it.

What distinguished the Progressive Era from the Civil War period was precisely this multidimensional quality. Where the slavery question had frozen politics into two opposing blocs, Progressive Era conflicts cut across existing party lines and identities, with minor parties playing a productive role by taking widespread advantage of fusion voting.

Economic reforms attracted both rural populists and urban progressives. Municipal reform drew support from business conservatives and good-government liberals alike. Labor issues forged unlikely coalitions between immigrant workers and native-born reformers.

Progressivism represented not a single movement but what historian Daniel Rodgers described as "shifting, ideologically fluid, issue-focused coalitions." Reform energy found multiple channels for release—through state and local governments, cross-party coalitions, and new social movements and organizations. The system behaved more like a liquid than either a solid or gas, with components free to form new bonds while maintaining overall stability.

This offers a crucial lesson for our own era of frozen politics: reform becomes possible when pressure can find multiple channels for release rather than building to explosive levels. Though the Progressive Era was certainly volatile, and many of its reforms were too anti-party for my taste, it did create space for the creative pluralism that we sorely lack today.

Where are we now? Not in a great state

Where are we today? To describe our current political situation, I'll use two metrics that correspond to our phase diagram's axes: electoral volatility (our political "temperature") and democratic constraint (our political "pressure").

First, let's measure electoral volatility. Political scientists Alessandro Chiaramonte and Vincenzo Emanuele have developed a straightforward measure of electoral volatility. They quantify how much total movement occurs when voters switch parties between elections. For example, if one party drops from 40% to 30% while another rises from 30% to 40%, that represents a volatility score of 10—indicating 10% of voters switched allegiances.

Applying this measure to recent U.S. presidential elections reveals a remarkably frozen system. For three elections in a row, the percentage support for Trump has been between 46.1% and 49.8%. The percent support for a Democrat has been between 48.2% and 51.3%.

This crystallization extends beyond the presidency. Consider that in the 2024 election 97% of House incumbents won re-election and state legislatures saw 95% incumbent retention. This is “calcified politics.”

“Politics feel stuck, something my colleagues and I call calcification. Calcification is like “polarization plus.” It’s not just that the parties are further apart, or just more polarized than ever before; each party is also more homogenous. On top of that, more personal, emotional, identity-inflected issues — like religious tests to enter the country, reproductive rights and immigration, as opposed to issues centered on the role and size of government — are the dimension on which politics is being contested, and this new dimension is made up of issues on which most people will not entertain a vote for the other side. Add that to the relatively equal power of the two major political parties over the last eight or so years, and we get to where we are today, with politics feeling stuck.”

In 2024, this calcification stood in deep tension with public demand for change. Polls showed roughly three in four Americans wanting major changes to the political system. But our single-winner election system, combined with geographic partisan sorting, has effectively frozen most districts into one-party dominance. A growing share of races aren't even contested anymore – especially at the state level, where more than half of races have only one candidate.

My contention is that without the ability to channel this desire for change into voting for different parties, frustration and pressure have weakened support for democratic norms. We now see increased pressure for illiberal actions, so long as they represent some kind of action.

We can observe this in our "pressure" metric—institutional constraint, measured through support for democracy Using Christopher Claassen's sophisticated measure (which combines multiple survey questions through a "dynamic Bayesian latent variable model"), we can track fundamental support for democratic principles.

Combining these two metrics, we see a decline in US electoral volatility and a decline in US citizen support for democracy.

What happened here? As American politics nationalized and polarized over the last three decades, voters became locked into increasingly distinct partisan loyalties. With fewer competitive districts and diminished cross-party cooperation, gridlock intensified. Rising frustration with this gridlock began eroding faith in democratic institutions themselves. The system froze up.A growing number of Americans (especially younger Americans) became disenchanted with democracy as a system. Many citizens became radicalized, especially on the political right.

As I argued in my pre-election piece, “Perfectly Balanced, Totally Unstable,” what appears as stability—consistent voting patterns and rigid partisan alignment—may actually signal a system approaching crisis. A collapse of political dimensionality into a single partisan axis has eliminated the cross-cutting issues and regional variations that once provided democratic resilience. This flattening of political space has coincided with our declining democratic health metrics, suggesting that too much stability—rather than too much volatility—may pose the greater threat to American democracy.

But how much volatility do we actually want? Finding the sweet spot

My contention is that the way out is to shift the lever towards a more dynamic and pluralistic party system by enacting proportional representation. But this worries skeptics of proportional representation, who paint dire pictures of a "gaseous" politics where chaos reigns. Careful, careful! they warn. If you think our politics is chaotic with just two parties, imagine how bad it would be with six! Or worse, imagine what would happen if we let everybody form a party!

Rick Pildes captures this anxiety in his recent law review article. As he warns: "This fracturing of power across more and smaller parties not only makes putting together effective governing coalitions more difficult; it also makes the political sphere more volatile. New parties pop up almost overnight and grab slices of power, including parties that style themselves as 'anti-parties,' reflecting a view that politics should somehow do away with parties altogether."

Pildes then tours through recent Western European democratic turbulence, chronicling rising volatility and right-wing populist parties in dark strokes. While Pildes correctly notes increased volatility in European systems, his descriptions run a bit hot. His portrait also misses some key comparative context: unlike the current MAGA-Republican Party in the United States, none of these European right-populist parties have come close to winning majority support. Most seem to have a ceiling around 20 percent. (I'll have more to say about this in a future post, after the upcoming German election in which the far-right AfD is polling around 20 percent, drawing its strongest support in post-communist East Germany.)

There are two ways to see the volatility of multiparty systems in Europe. One, Pildes’ perspective, is that it signals a kind of political deterioration. An alternative perspective, which I hold, is that this volatility reflects democratic systems successfully managing challenging pressures while maintaining constitutional norms — unlike in the United States.

So yes, volatility has increased since 2008 – when a financial crisis sent European politics reeling. Voters reacted to the convergence of center-left and center-right on neoliberal "third way" politics of Europeanization and globalization.

Given this centrist convergence and the 2008 crisis, European voters did exactly what you'd expect - they sought alternatives. Because PR systems permit smaller parties, voters found those alternatives, driving increased volatility. By one analysis, 75% of election-to-election volatility came from straightforward party switching, 17% from turnout differences, and 8% from generational replacement. Indeed, post-2008 young voters brought different concerns and values than previous generations.

This points to a crucial contrast: In European systems, young voters stay politically engaged because they can support parties that speak to them. In America's two-party system, younger voters have grown increasingly alienated from the two major parties - and this alienation corrodes democratic support. And yes, some of those younger voters in Europe are supporting far-right parties. But most aren’t.

Some volatility serves democracy well. Established parties can grow sclerotic; periodic disruption keeps the system dynamic, and responsive. Competition has driven human progress for millennia. But excess volatility breeds dangerous uncertainty and anxiety, pushing us toward that "gaseous" state of political chaos.

This also highlights one problem with some good government reformers' fixation on electing "moderates" and representing the mythical "median voter" - convergence toward the center can deprive voters of meaningful choice and authentic representation. But that's a different discussion.

American Exceptionalism: uniquely calcified politics, distinctly declining support for democracy

Comparative data reveals America as a unique case of insufficient political volatility and declining support for democracy. Here’s my visualization of the data:

While some European democracies have experienced electoral volatility, their citizens' support for democracy has remained stable. Even in countries where support for democracy previously declined (Germany, the UK), increased electoral volatility has corresponded with renewed support for democratic institutions. If anything, more electoral choice corresponds to more democratic resilience!

European party systems could certainly become excessively volatile, further complicating coalition formation or elevating anti-system forces to positions of greater authority. Every political system has absorption limits. However, the data suggest that moderate volatility—the kind that proportional representation enables—may actually bolster democratic resilience rather than undermine it.

How to exit a constitutional crisis: engineering a controlled phase transition to fluid pluralism

My view is clear: we should turn the electoral lever firmly toward more parties and more proportionality, but not all the way. Modest proportionality offers the right balance.

In turning the lever toward a more permissive electoral system, however, let's not get hung up on worst-case scenarios. No serious advocate of proportional representation suggests adopting the Dutch model of one national 150-seat district, where parties can win seats with less than one percent of the vote. Nor should we emulate Israel's system, where a 3.25 percent threshold has created its own perverse consequences. All current proposals I've seen wisely anticipate modest district magnitude, following political science wisdom about the "electoral sweet spot."

Some skeptics of proportional representation have also proposed more minor reforms- tweaking primary systems, implementing ranked-choice voting, or trying to create more competitive districts through independent redistricting. But these reforms barely nudge the lever. For reasons I've detailed elsewhere (click the links above), these reforms apply insufficient and frankly misdirected pressure to get us back to genuine, multidimensional pluralism.

The election system serves as our master lever, directing demands through the system. The political thermodynamics framework, however, makes clear the challenge we face. We must simultaneously strengthen our democratic institutions and our democratic commitments. Reaching the liquid state requires movement along both dimensions – allowing more electoral dynamism while also restoring constraint. Moving the lever is delicate work, demanding careful calibration.

The good news is that there is already a vast infrastructure of organizations working to restore democratic guardrails - to rebuild civility, trust, and faith in civic institutions. Their work matters deeply. However, without turning the electoral lever to redirect angry demands into constructive new coalitions and parties, these efforts at civility and trust-building will likely falter. The pressure to ignore norms and just fight harder will just continue to build.

The path forward requires both civic strengthening and structural electoral reform. Neither alone suffices.

On the current trajectory, the calcification will only continue into 2026. Early estimates place 18 House seats (4%) as genuine tossups, with another 21 (5%) categorized as "lean" - meaning just 9% of districts are likely to see much real competition. (Democrats currently hold 22 of these 39 competitive seats). The Senate map appears equally frozen: just 4 tossups out of 33 races, plus 2 "leans." This rigidity leaves precious little space for the electoral dynamism a healthy democracy requires. Absent reform, we will likely remain stuck in a politics that descends into competitive authoritarianism.

Big change, like a phase transition in physics, can seem impossible until suddenly it isn't. A watched pot of water never boils. Until it does. Too many couldn't imagine our current constitutional crisis. Now, too many can’t imagine a more fluid, dynamic system.

But phase transitions work in both directions.

I agree with Paul Cohen that more parties and more proportionality are needed, but how do we get the changes made. I don't believe that it will happen from the top, so it needs to get started from the bottom. The Forward Party has had limited success with this model and is continuing to work with individuals in each election and many voters are aware of the need for change yet are skeptical that it can be done. It would be a great thing if a way to get voters involved more quickly.

As others have said, this is a very compelling argument, but there's not an obvious way to get from here to there. It's hard to imagine either current political party to push for this effectively. It would be perceived as unsupportable by the other party. And cf other commenters, it's hard to imagine a slow state-by-state approach working either. It would be way too slow to deal with the current anti-democratic threat, and implemented in most states would essentially be a unilateral disarmament for whichever party is currently dominant. Not happening.

So I tend to think that it needs to happen all at once, in a grand bargain at a constitutional convention. The alternatives involve violence (which is bad), or dis-union (which is bad). Or failure to retain democracy (which is at least as bad).