Perfectly Balanced, Totally Unstable

The dangerous strangeness of our perennially too-close-for-comfort elections

"How can it really be this close?"

As we count down to Election Day, I keep hearing this same question over and over.

"How can it really be this close?"

Political junkies ponder the mathematical improbability. In a vast, diverse nation of 335 million, how indeed can our elections remain so perfectly balanced between two bitterly opposed parties, election after election after election after election? Is some greater force keeping us locked in 50-50 purgatory? Does neither party really want to win? Or is it just pure chance?

My liberal friends, meanwhile, ask with mounting exasperation: “How can it be this close? Why aren't Democrats running away with this? How can anybody possibly be voting for Trump? He’s an authoritarian racist, don’t you know?” (Even David Brooks is stumped.)

I have straightforward answers to these immediate questions about the closeness. But this essay will mostly focus on a bigger and more existential question of what it all means: What does this puzzle of persistent parity portend for our democratic health? Is this a healthy equilibrium? Or are we on the precipice of breakdown?

I see it a precipice. Drawing on complex systems analysis, I’m going to dig deeper into three key danger signs that our political system is approaching a critical threshold:

The collapse of dimensionality: How our rich political universe has compressed into a single, apocalyptic partisan axis, eliminating the multidimensional resilience that once kept democracy stable

The "critical slowing down": Why our system's ability to process change and adapt to new challenges is stuck in gridlock.

The flickering bi-stability: How sudden, wild oscillations between political extremes are destabilizing our institutions and setting the stage for potential catastrophic change

I'm not hopeless: there is a way up and out. But finding it requires expanding our perspective beyond just one election, or even one era. We need to think bigger, more systematically, and more multidimensionally about both the problem and potential solutions.

But let’s start first by explaining why we are deadlocked.

The Narrow Logic of the Minimal Winning Coalition – Keeping it Tight

At the core of America’s wafer-thin electoral margins lies a simple strategy: the “minimal winning coalition.”

The logic, as William Riker explained in his 1962 classic The Theory of Political Coalitions, makes perfect sense: In zero-sum political competition, rational party leaders will build the smallest coalition capable of securing victory. Why? Larger coalitions are harder to manage. They make distributing benefits harder. Smaller winning coalitions minimize internal tensions. Larger winning coalitions demand more complicated compromises.

This strategic logic creates a self-reinforcing cycle. Narrow margins of minimal wins raise stakes. High stakes strengthen coalition cohesion. When elections are consistently close, competing parties dig in and elevate conflict. Each side's base becomes more committed – and more fearful of the other side gaining power.

This competitive equilibrium appears stable on the surface—after all, both parties remain viable and neither collapses. Complex systems theory suggests that an equilibrium maintained through constant, artificial pressure often signals danger rather than true stability.

This dynamic helps explain why so many voters stick with Trump. They're locked in the informational and social world of the Republican minimal winning coalition. A shared enemy is the glue that holds the coalition together. Republican leaders constantly remind Republican voters how dangerous Democrats are. Democrats do the same. This election, an impressive 87% of voters said they “believe America will suffer permanent damage” if their side loses.

Round and round we go. The closer the margins, the higher the stakes. The higher the stakes, the stronger the cohesion. The stronger the cohesion, the closer the margins. Round and round. Wheeee.

(And yes, it's true that our electoral institutions systematically advantage Republicans, allowing them to potentially control the federal government even when Democrats win more total votes. While I believe this arrangement is fundamentally anti-democratic, it reflects long-standing rules of the game around which both parties have built their strategic coalitions. Different rules would yield different coalition-building strategies, but the underlying minimal winning coalition logic would persist.)

The Great Flattening: How American Politics Lost Its Dimensionality

Sixty years ago, American democracy was a two-party system in name only. Both parties contained multitudes. Alabama Democrats had little in common with New York Democrats. Vermont Republicans operated in a different universe from Arizona Republicans. State parties were distinct, rooted in local soil.

This pluralism created flexibility. When new issues emerged, they didn't automatically map onto existing partisan divides. Civil rights split both parties. So did gun ownership. And abortion. And frankly, most of the issues that now divide the parties once split them. But those all weren’t national issues … yet.

The 1970s marked the beginning of the great flattening. Activist groups began nationalizing political issues. Civil rights realigned the South. Evangelical Christians entered politics as a bloc. Gun rights became a partisan marker. Abortion turned into a party-defining stance. Issue groups and parties formed more distinct teams. Politics regionalized and nationalized around culture war issues.

In some cases, presidential election campaigns and administrations pulled in supportive groups. In other cases, activist groups recruited and supported their candidates and helped them win party nominations, up and down the ballot.

Here, the image that keeps popping into my head is the Democratic and Republican parties as two dominant and greedy suns, absorbing everything nearby, blocking out each other’s light.

Those orbiting the Democratic "sun" perceive one reality. The light of their reality, however, does not penetrate the field of those orbiting the Republican “sun.” This helps explain why so many people are voting for Donald Trump. The light of their sun broadcasts a different reality.

Two giant unstable stars dominating a political universe can warp political space-time. I’m no astrophysicist, but it seems dangerous to me.

An excellent big-picture guide to this development comes from Partisan Nation: The Dangerous New Logic of American Politics in a Nationalized Era, by political scientists Paul Pierson and Eric Schickler. They detail how this pluralism collapsed. They argue today's polarization is distinctive precisely because it's national and thus self-reinforcing.

As Pierson and Schickler argue, this dynamic fundamentally challenges our constitutional system. In the past, "Key features—the character of state parties, the nature of group organizations and demands, and the structure of the press—acted as effective countervailing mechanisms against the risk of fierce and sustained polarization.” But not anymore: “Today's polarization has followed a different path."

I describe this change as a flattening of dimensionality because we often talk politics with the location markers of left, right, and center along a one-dimensional line.

However, as I’ve argued in a previous essay, this one-dimensional framework – and its obsession with the “median voter” as pivotal – is both misleading and harmful. Where I can, I’ve always tried to map politics in at least two dimensions. (You may even know my nerd-famous scatterplot, with the “quadrants” - Figure 2 in this report)

So what do I mean here by dimensionality?

Think of it this way: there are a lot of issues in politics that don’t necessarily need to get bundled together. For example, labor rights and immigration. There is nothing inconsistent about supporting permissive labor rights and lower immigration, or the reverse combination (limited labor rights and higher immigration). However, if these were your top two issues, you would have to decide which was more important to you. In voting, you must choose between the Democrats’ bundled position (more support for labor rights, higher immigration) and the Republicans’ bundled position (less support for labor rights, lower immigration).

With four parties, you could envision all four possible combinations represented by a different party. If this were the case, politics would have two separate issue dimensions — labor rights and immigration. By bundling these issues together into one platform, Democrats and Republicans have combined them into one mega-issue: Democrats vs Republicans. The fancy word for this is “ideological coherence.”

Prior to the mid-2000s, labor rights were a central aspect of the Democrat vs Republican conflict. But immigration policy was not. Republicans and Democrats had internal disagreements. The issue split the parties, and varied more by region.

Multiply this across more issues, and you can see how these cross-cutting issues once made politics multidimensional, and more flexible. It left open space for creative compromises, and for many voters to reconsider their allegiances from election to election.

This big-tent heterogeneity also complicated the logic of the “minimal winning coalition” – the parties were often so incoherent that nobody could maintain order. State parties, media organizations, and interest groups were all too independent of each other. It was a complex multidimensional pluralism that mitigated polarization.

Yes, the political system was often chaotic. But it was also resilient. It navigated the heightened racial and anti-war conflicts of the long 1960s.

Today’s party and political system is entirely different. It is almost completely one-dimensional. Today, every single issue of national importance is partisan. State parties march in lockstep with national parties and re-double the national conflicts. Media organizations are partisan. Few interest groups are independent of the parties.

Let’s look at the data. Measuring the "dimensionality" of Congressional voting - that is, how well a one-dimensional liberal-conservative model explains roll call behavior - reveals a distinct rise towards uni-dimensionality over the last four decades. Today's Congress is now nearly perfectly aligned along a single partisan axis — a first in the history of our Congress.

The same pattern holds across a wide range of policy domains. As political scientist Ashley Jochim and Bryan Jones have documented, "the majority of issues" - from healthcare to education to civil rights - "have evolved from multidimensional spaces to unidimensional,” as the stellar logic of party polarization pulled all issues into its gravitational fields. Even agriculture policy, once largely off the partisan radar, has been sucked into the vortex of polarized alignment, as Dustin Wahl and I wrote about back in January.

(Specifically relating to Congress, I wrote more about these trends in my essay last year, “The U.S. House has sailed into dangerously uncharted territory. There’s no going back: Seven data points mapping the weirdness of this moment, and a plea for reform.”)

A Democracy Approaching Flatline – The Critical Slowing Down?

In medicine, a flatline means crisis. A healthy system—whether it's a human body or a democracy—should show constant rhythms and fluctuations. When a system becomes static, stuck in a single state, that's usually a bad sign.

Here's the thing: American politics is flatlining. For nearly a decade, our political system has shown an eerie same-same consistency in voting patterns. Since 1992, the balance of power in Washington has oscillated between Democratic and Republican control, following small shifts in national vote totals. Counties vote the same way, year after year.

Consider what hasn't changed our voting patterns:

A global pandemic

A former president being convicted of one crime and indicted for multiple other crimes

An economic downturn and record inflation

Climate disasters increasing in frequency and severity

An insurrection at the U.S. Capitol

A Supreme Court overturning long-standing precedents

Rapid changes in technology and media

Political scientists John Sides, Chris Tausanovitch, and Lynn Vavreck call it "calcification." In their book The Bitter End, they document how our political system has hardened into unprecedented rigidity. No amount of campaigning, new information, or constitutional crises seems to shift the underlying dynamics. The stunning stability of the 2024 polling is remarkable proof of this description.

In a 2021 FiveThirtyEight piece (“How Much Longer Can This Era of Political Gridlock Last?”), I documented two striking data points that illustrate this spooky stability. First, a record-breaking nine consecutive presidential elections where neither party achieved a true landslide (defined as a 10-point popular vote margin). The previous record was just seven such close elections in a row. We’ll certainly make it 10 in a row this year.

Second, an unprecedented seven straight presidential cycles where fewer than a quarter of states changed partisan control—obliterating the prior record of three. This streak will also surely continue.

A decade ago, Washington conventional wisdom held that eventually "the fever would break." The assumption was that escalating partisan polarization was temporary. The system would naturally return to its previous relatively healthy pattern of relationships.

That belief reflected a core principle of resilient systems: they tend to return to a previous pattern after a disturbance. Most people thought American democracy was still fundamentally healthy and resilient. Turns out, it was not.

Healthy democracies depend on two master norms, as Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt argue in How Democracies Die: mutual tolerance and institutional forbearance. But despite the hopes of a breaking fever, our system hasn't returned to these norms. The fever is even worse. We are indeed in a doom loop.

The Republican Party's transformation under Trump has accelerated the damage. January 6th didn't trigger a reset. Instead, anti-democratic forces have strengthened. A second Trump administration advertises a very dark journey into the democracy-destroying depths of vindictive illiberalism.

Complex systems theorists have a name for this phenomenon of a system getting stuck and not returning to its healthy state: "critical slowing down."

It's a classic warning sign that a system is approaching a tipping point or phase transition. Like a tightrope walker balancing on a fraying rope, the American political system maintains its surface-level balance through increasingly extreme, unsustainable adjustments.

Flickering Bi-Stability: Democracy’s Warning Lights are Flashing

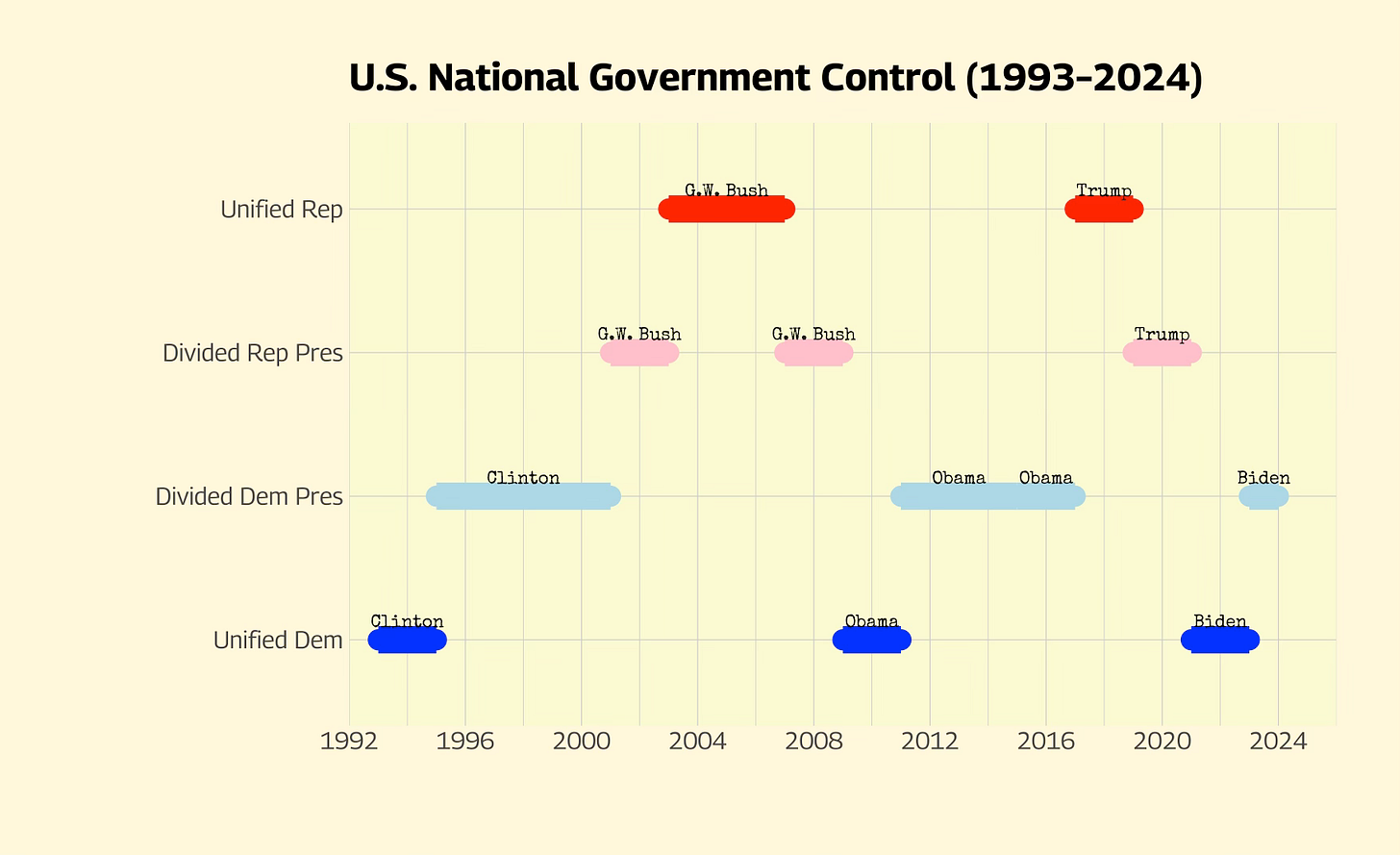

Since 1992, control of the national government has followed a flickering pattern: Democratic trifecta to divided government to Republican trifecta to divided government, then back again.

This is new in American history. In my above-mentioned FiveThirtyEight piece, I looked at how much flickering took place in different political eras. This current era has experienced an unusual amount of flickering. (The graph below only went to 2020, but 2022 reflected another flicker; Republicans re-captured the U.S. House)

While surface-level national partisan balance is similar from year to year, each shift in partisan control further stresses the governance capacity. This erodes institutional strength and trust.

Today, a shift of a few thousand votes across three states—far less than the attendance at a single Taylor Swift concert—could give either party complete federal control.

A Republican trifecta could ban abortion nationally, gut environmental regulation, transform immigration policy, and enable the vengeful illiberal fantasies of Donald Trump and his allies.

A Democratic trifecta could expand healthcare access, pass climate legislation, enshrine a right to abortion.

Small shifts, massive perturbations. Each oscillation brings more dramatic policy reversals and more extreme executive actions, placing greater strain on our institutions.

These rapid shifts between extremes show three worrying characteristics of a system losing stability:

Increasing Amplitude: Each swing brings more dramatic policy reversals and more dramatic executive actions.

Shortening Recovery Periods: The system has less time to absorb changes before the next reversal.

Accelerating Institutional Erosion: Each partisan governing swing further depletes governance capacity and institutional trust.

This is what scientists sometimes call "flickering bi-stability." It’s not something you want to see in your complex system of choice.

Something has to change. But what and when?

I don't know exactly how this resolves. But it feels like our political system is approaching a critical point. It has been stuck in a precarious 50-50 balance for too long, and it can't stay this way forever. At some point, the pressure will rupture the balance.

Of course, a seemingly unsustainable state can drag on much longer than anyone expects — as I argued in an earlier essay ("American politics feels weird because it's jammed between two states — the old and the unknown”). But nothing lasts forever. The longer we maintain a surface deadlock, the more violent the eventual shift could be.

So, what happens when the breaking point comes? I fear the answer may be something quite radical, especially if the current deadlock holds even longer. The more we deny the need for change, the more catastrophic that change could be.

I have my own ideas about what I'd like to see come next. My vision of a healthy democracy is a vibrant, organized society — one with multiple healthy political parties rooted in civil society, where groups and identities are pluralistic and, most importantly, overlapping. It’s a society with a shared commitment to dynamic conflict as the best way to resolve our inevitable disagreements.

But I’ve been reading the news, too. A dystopian future of a fascist police state, built on distrust and disinformation, seems all too imaginable given our current political trajectory.

And much as I hate to acknowledge it, my readings into complex systems (and history) point to an unfortunate pattern: sometimes collapse is necessary for renewal.

This idea goes against our instincts for control. But there it is.

Take forest management. Turns out, small fires are vital to a forest's long-term resilience. These small fires clear out accumulated fuel, make space for new growth, and bring nutrients back into the soil. Without them, tall trees crowd out everything else, making the whole forest vulnerable to devastating wildfires. Recognizing this, The U.S. Forest Service has now shifted its stance on the old Smokey the Bear message. Turns out, suppressing every fire only makes larger fires more destructive. The ancient wisdom of controlled burns was right: small disruptions build resilience.

The analogy to politics isn’t perfect. But it is eerily resonant. Here we are — decades into a rigid, calcified era of American politics, where political diversity is shrinking, two-party competition is hardening, systemic pressures keep mounting, and dry tinder is everywhere. It's no wonder that so many feel the urge to "burn it all down."

The Rigidity Before the Revolution?

Complex systems can appear hopelessly rigid right before transformation. Yet beneath seemingly calcified patterns, the potential for renewal often lies dormant. Consider again our forest management analogy: After decades of fire suppression, forests don't just contain accumulated fuel—they also harbor dormant seeds awaiting an opportunity.

Electoral reforms like proportional representation and fusion voting could shatter the zero-sum logic that flattens our politics. By creating space for new parties and issue-based coalitions, such changes would unleash the multidimensionality our system needs to adapt and thrive.

But this election season, another promising path is emerging. In Nebraska, Independent Senate candidate Dan Osborn is charting one way to shake the system within the existing structures.

His populist campaign pulls together an unconventional coalition of rural voters, union members, and disaffecteds. Polling shows a dead heat. It is conceivable that Osborn could be the 51st vote in the Senate come 2025.

We need many more "Osborn-style" candidacies, as Perry Bacon Jr. compellingly argues in a recent column (“We need new political parties in very blue and very red states”). Such campaigns could reintroduce much-needed competition and accountability to elections that have become mere formalities. They could force a reckoning with substantive concerns obscured by the red-blue divide, adding some much-needed dimensionality and diversity back to revive our flattened politics – and ideally create momentum and support for the bigger structural reforms.

So back to the original question: "How can it really be this close?"

It's close because we've built a political system that demands and reinforces that closeness. But understanding this dynamic gives us the power to change it.

The path forward isn't through one side finally vanquishing the other in our endless partisan battle. That is not going to happen – at least not peacefully. And violence could throw us into a new, much worse equilibrium.

The answer is in breaking free of that binary altogether and rebuilding the multidimensional, resilient democracy America needs to navigate the challenges ahead.

The choice is ours. We can remain trapped in our precarious partisan parity until it breaks catastrophically. Or we can begin the hard work of democratic renewal now, creating space for the new political alignments and institutions our future requires. The warning signs are flickering and flashing. The time for action is now.

Another factor that supports your claims is death of the Constitutional Amendment as a part of American politics. Up until the 1970s/80s (a time period you highlight) Constitutional Amendments were a regular part of the American political system and since there has only been one and it has an asterisk. When was the last time there was a sustained effort at an Amendment? I have never seen what a campaign for an amendment looks like - hell my parents were of an age that they got the right to vote in 1972 because of the 26th amendment. Just another point in your argument's favor is that we have given up on the idea that our institutions can and sometimes should change, but there was a time where it was normal.

Thanks for this and your analysis. Can you share your thoughts about mounting extremism in Europe and parts of Asia, where multiparty politics exists and is enshrined? I'm not sure why this is the answer given that...