The Paradoxical Reason Republicans Win Elections Despite Unpopular Policies

Plus, exciting news from New Jersey

Hello. It’s been a few months. I’ve been distracted, hard at work on an exciting new project I’m eager to share with you all soon.

But in the meantime, I went digging through the 1976 issues of the European Journal of Political research to excavate a paradox to explain today’s politics. I also recorded some podcasts. And I’ve been cheering on as fusion voting gains support in New Jersey.

In this edition….

Can The Ostrogorski Paradox explain why Republicans often win despite unpopular policies?

Or, why issue bundling blows up Democratic theories about how to win elections.

A political puzzle haunts Democrats. Public opinion aligns with Democrats across almost all major policy issues. Yet, every national election is close. Very close.

A majority of the public agrees with Democrats …. on economic issues. On healthcare. On modestly progressive taxation. On abortion. On (not) criminalizing gender transition-related medical care. On (not) restricting drag show performances. On doing something about the warming climate. On (not) banning books. On guns.

And yet. Republicans might still win unified control of Washington in 2024. If they lose, it will only be narrowly.

So why are elections still so close?

Two words: Issue bundling.

In a two-party voting system, voters must prioritize issues. Even though Republicans may hold unpopular stances, it’s the bundle, not the individual issues, that matters.

Huh? The bundle? What, you say?

Stick with me.

(And yes, there are other plausible explanations. Gerrymandering did it! Issues don’t matter! Voters are misinformed! I’ll get to those. They also explain a few things.)

But, here’s my big argument for today: Even if voters were fully informed, even if they voted on the issues, and even if congressional districts were all drawn fairly, Democrats might still lose a head-to-head election against Republicans — despite having the more popular policies.

How is this possible?

Enter… The Ostrogorski Paradox

Moise Ostrogorski was a Belorussian political sociologist. In 1902, he published the classic Democracy and the Organization of Political Parties, after studying US and British parties. The book is quite pessimistic on mass political parties and their tendency to devolve into corrupt, top-heavy bureaucracies — a theme developed further by the Italian Robert Michels in his 1915 book Political Parties, which is remembered for its “iron law of oligarchy.” (The “iron law” is that all organizations, including political parties, eventually become oligarchic).

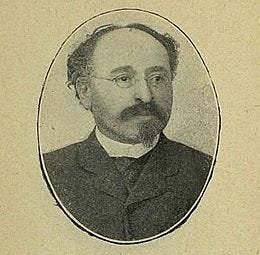

Ostrogorski (pictured above) did not invent his eponymous paradox. The political scientists Douglas W. Rae and Hans Daudt conjured it in 1976. They named it for old Moise, "for it was he who devoted his major work to the proposition that all manner of mischief can result when issues are mixed together in a single contest."

“when issues are mixed together in a single contest….” In other words, bundled.

Let’s start with the original table Rae and Daudt use in their European Journal of Political Research article, “The Ostrogorski Paradox: A Peculiarity of Compound Majority Decision”

The example imagines two parties, the Red Party and the Black Party, and three issues, cleverly named 1,2,3. The parties take opposite positions on each issue.

Group D is all in for the Reds. But Group D is only 40% of the voting population.

Groups A, B, and C, are more complex. They each agree with Black Party on two issues, and the Red Party on one issue. So they vote Black. The paradox arises because three groups vary. But, on balance, each should prefer the Black Party.

The Red Party has more unified ideological support. The Black Party wins from diversified ideological support, appealing to different groups.

Hence the paradox, as Rae and Daudt explain it: “If during an election each voter picks the party with which he agrees on a majority of issues, it is nevertheless possible that a majority of voters disagrees with the winning majority party on every issue.”

But wait… it could be even worse

The above example assumes voters weigh issues equally. It could be even worse. Voters might prioritize. And intense minorities might care only about a single issue. And they might band together to win.

Imagine a voter group focused solely on one issue, willing to support a party despite differing opinions on two of the three issues.

In this scenario, 80% of voters may align with the Red Party on the issues, yet the Black Party secures 60% of the vote when policies are bundled in a head-to-head election.

Rae and Daudt diagram how:

Essentially, groups A, B, and C passionately focus on one issue each, forming a pact to mutually support one another in achieving their goals.. If they hold together, they can all get what they want most. It’s how intense minorities can rule over a majority. Call this the “Minorities Rule” paradox.

But bundling depends on the forced-choice binary. If issues are unbundled, minorities can’t rule.

Turning to the Data: How Republicans benefit from internal dissensus

Here I’ll take on four topics — Abortion, healthcare, immigration, and January 6. These are not exhaustive, but they are all topics that dominate politics.

Democratic politicians oppose Dobbs, believe government should provide healthcare, believe illegal immigrants should have a path to citizenship, and believe that the actions of Trump supporters on January 6th constituted an insurrection. Republican politicians hold the opposite position. Democratic positions are broadly more popular.1

So far, so good. It gets more interesting when we count up partisan agreement across the four issues. The next table breaks down the electorate into groups based on how they align with the two parties across the four issues. Then we show their likely 2024 vote. Percentages don’t total to 100 due to undecided or non-voting respondents.

Start with the top two rows. About 42 percent of the electorate are consistent partisans, in that they agree with one party on all four issues, and overwhelmingly support their party’s candidate for president.

But the share of voters who agree with Democrats on all four issues (27.2%) is almost twice the size of the share of voters who agree with Republicans on all four issues (15.1%). Democrats are more unified ideologically.

But what Republicans lose in universal agreement, they gain in voters who will vote Republican despite some disagreement. Compare: Among voters who support Democrats on three of the four issues, but support Republicans on one, Biden has only a 54.2% to 21% edge. But among voters who agree with Republicans on three of the four issues, but Democrats on one, Trump has a 70.2% to 4.4% edge.

Perhaps even more consequential, among voters who agree with both parties on half the issues (7.4% of the electorate), Trump has a 49.4% to 27.5% edge.

What’s happening here?

It appears to be a mix of both explanations — the Ostrogorski Paradox and the Minorities Rule paradox.

Democrats have solid support from majorities on each issue on its own. When issues are bundled, Democrats hold the majority in 54% of bundles, while Republicans claim 46% of them. That is much closer than a policy-by-policy vote would be. The bundling of unpopular stances appears to help Republicans. Voters in Red States might support a living wage, or a Medicaid expansion, or protections for abortion on their own. But bundle them together, and choices are different.

The Ostrogorski Paradox makes the election closer than it should be. Then, intense minority support makes it even closer. Republicans also benefit from intensity of support. When voters trade-off across policies, they put more weight on the issues where they agree with Republicans.

If you want a more exhaustive analysis of how issues split voters, my New America colleague Oscar Pocasangre and I did a very comprehensive report last November, focused primarily, but not exclusively, around swing voters.2

Why bundling blows up Democratic theories about winning elections

Democrats currently have two dominant theories about how they win more elections. Neither addresses the issue bundling problem.

The first theory is “we must level the playing field.” Here’s the idea: Our electoral institutions are all biased in favor of Republicans. If everything were on the level, Democrats would win.

Certainly, our electoral institutions are biased towards rural and exurban over-representation, which helps Republicans. And certainly, a basic foundation of representative democracy is that all voters should count equally, regardless of where voters live. Our electoral system clearly does not count all voters equally.

But: Republicans won the popular vote for the House in 2022, a slightly uncomfortable fact for “we must level the playing field” theory.

The second theory is “we just have to message better.” This is sometimes called “popularism.” Leading up to the 2022 midterms, Democratic and Democratic-adjacent pundits spent lots of time arguing over what seemed like a relatively non-controversial theory of winning elections: That Democrats should just say and do popular things, repeatedly, and eventually it would break through. Many smart criticisms followed, but the criticism is here relegated to a summarizing footnote to avoid a distracting tangent.3

But here’s the big point: Neither of these theories explains why elections as close as elections are. Again: Republicans have very unpopular policies, but still won the popular vote for the House last year.

How do we break the paradox? Un-bundle! More parties.

To keep “on brand”, this is where I will point out that this is only possible through binary bundling. Binary bundling follows from the “compound majority” aspects of two-party voting. In a two-party system, there can only be two bundles. But the more parties, the more possible bundles.

If we had, say, six parties, different parties could come up with different issue position bundles and priorities. Voters would not face the same trade-offs. Majorities could be more complex, and more fluid.

This would be a more representative system. The forced-choice binary is artificial and dangerous. Even on the four issues discussed above, most voters hold some mix of Republican or Democratic positions.

This might help Republicans win some elections, but it doesn’t help Republican voters, who often disagree with their party on major issues. If voters had more options, many could vote for a party that better represented their values and fought for them in making policy. Then representatives could bargain to work our reasonable compromises with majority support.

So, how might we get more parties? Well, let’s take a quick visit to New Jersey, where a potentially ground-shifting court case is proceeding apace.

Fusion voting gains support in Jersey

Will the Garden State be the garden of democracy reform?

As you may remember from a previous editions of Undercurrent Events, I’ve been closely watching developments in New Jersey — in particular a case moving through the state Supreme Court, which would re-legalize fusion voting.4

So I was delighted to read a recent opinion piece in the Newark Star Ledger by Christine Todd Whitman and Robert Torricelli. (Whitman as in former Republican Governor Whitman. Torricelli as in former Democratic Senator Torricelli)

As they write…

“Sometime in the next several months, the New Jersey Supreme Court will likely decide a monumentally important case – Moderate Party v. New Jersey Division of Elections – that has the potential to reshape and improve politics in America. Indeed it has the potential to break this cycle of hyper-partisan polarization, a cycle that fills most Americans with despair. Let us explain….

The answer is not, as some imagine, to try to get rid of parties or partisanship. Competent political parties serve a crucial function in politics because they give voters clear ways to express their values; we don’t want to destroy them, we want to change the incentives that drive their behavior. Parties can be a source of stability, strength and even innovation in our democracy.

One way to do that — and this may strike readers as counter-intuitive — is to open the two-party system to more competition by reviving and re-legalizing “fusion” voting. Fusion voting means that a candidate can be nominated by more than one party, and voters then choose not just the candidate they prefer but also the party that is closest to their values. Under the current rules, established a century ago in almost all states, the two parties have a functional monopoly on power. Third parties are permitted to form, but the rules against cross-nominating a major party candidate keep them stuck in the “wasted vote” or “spoiler” box…

….The systemic benefits of fusion could be substantial, by tempering the destabilizing effects of hyper-polarization and by incentivizing parties and candidates to compete for voters in the middle. But legalizing fusion would also empower the individual voter, especially one frustrated with our two major parties. A vote for a candidate on a centrist party’s line would be a powerful and effective way to signal that you favor problem-solving over posturing and to reward politicians who are workhorses instead of grandstanders.

Bringing back fusion would strengthen the center of American politics. Otherwise, we’re trapped in a badly-designed game that is now driving our country toward a cliff.

I was equally delighted to read a follow-up editorial by the Star Ledger, enthusiastically endorsing fusion voting.

As the editorial board explained:

“If you were an independent and couldn’t bring yourself to pull the lever of either major party, you were out of luck. And unless there is action in the courts or in Trenton, it will remain that way. The status quo upholds party sovereignty, which is unfair, given that there are more unaffiliated voters in New Jersey (2.5 million) than Democrats or Republicans.

And they want their voices heard. Just ask them.

An FDU poll from February showed that 56% of New Jerseyans from across the spectrum support fusion voting, while only 32% oppose it. Remarkably, it has 59% support in urban counties dominated by Democratic machines (Essex, Hudson, Mercer, Middlesex, and Union) and a whopping 66% support in Republican-leaning coastal counties (Ocean, Cape May, Atlantic and Monmouth).

Poll director Dan Cassino believes the reason is simple: The system needs reform, and everybody knows it.

“The argument against fusion ticket laws has always been about maintaining stability,” Cassino said. “But when both sides are unhappy with the way their parties are going, that stops being a compelling case.”

And finally, I was delighted to learn that the case will indeed proceed as planned, despite the attempt by both parties to set the case back. In late March the NJ Attorney General (a Democrat) filed a motion to dismiss the challenge to New Jersey’s ban on fusion for improperly presenting a constitutional issue, or in the alternative, to transfer the appeal to the trial court to re-open the appellate record. The NJ Republican State Committee (in their role as intervenor) joined that motion, and further requested that the appendix accompanying our opening brief be stricken.

The Appellate Division denied the motions. This means that the briefing should be complete by mid-summer. Stay tuned.

What is nationalism? What is populism? What is democracy? Are six parties better than two? And are open primaries unconstitutional?

Some recent adventures in podcasting

And finally, while I’ve got you, I’ve got a bunch of recent episodes of my podcast, Politics in Question, to share with you.

So many conversations, so little time, I know….

But going back to March, we’ve got my conversation with Rick Pildes, the Sudler Family Professor of Constitutional Law at the New York University School of Law. Rick and I agree that political parties are incredibly important and should be strengthened. But we disagree on whether this is possible within a two-party system. Rick thinks it is. I disagree, and argue we need proportional representation. Rick disagrees. It’s a spirited and lively discussion. You won’t want to miss it. Click here for the episode.

Continuing on the theme of political parties, you’ll also definitely want to listen to my conversation with Tabatha Abu El-Haj, professor of law in the Thomas R. Kline School of Law at Drexel University. Tabatha has a very appealing vision of what healthy parties look like, and tremendous insights on how and why the courts put their thumbs on the scales of justice to protect the two major parties. Also, Tabatha explains why open primaries are likely unconstitutional. Click here for the episode.

Also of recent vintage, Julia Azari and I talked to Nicholas T. Davis, an assistant professor at the University of Alabama, and co-author of Democracy’s Meanings: How the Public Understands Democracy and Why It Matters. Turns out, we don’t even agree on what democracy means. Which raises the obvious question: how can we have a democracy if we have different ideas about what democracy is supposed to be? Good question, right? Click here for the episode.

Finally, you won’t want to miss the one where Julia and I talked to Bart Bonikowski, an associate professor of sociology and politics at New York University, about populism and nationalism. Bart sees the commonalities between nationalism and populism across the US and Europe. And listen to the end, when we talk about how political institutions matter, and why proportional multiparty systems are better equipped to manage populist nationalism. Click here for the episode.

That’s all for this edition. The paradox is what to do next.

One possible next action: Go ahead, press all my buttons …

Yes, there are different ways to ask these questions. And yes, these are not the positions of every Democrat or Republican. This is not a one-to-one map of the world.

….in which we also found a large share of the electorate not fully aligned with either party on the issues. Republicans were more ideologically heterogeneous than Democrats. Since it was election time, we focused on swing voters. Our point was that they were a wild menagerie of left and right policy sympathies. There was no simple formula for winning them over.

As we wrote, “the persistence of an unpredictable and inconsistent group of undecided voters holding the balance of power raises serious questions about whether elections in the United States reflect an accurate aggregation of the people’s will or a series of lucky draws.”

I had hoped that our report would get more pick-up since it had so much good stuff in it. It still does. And it’s still relevant. Voters are still more complicated than the us vs them national political fight. And Democrats’ high internal policy agreement still hurts them electorally.

The other side of the “popularism” debate argued that issues don’t matter as much as you think. Politics is about more than issues. It is about identity. And even if voters might agree with Democrats on policy issues, they just don’t trust Democrats to actually follow through, because they don’t think Democrats care about “people like me.” Moreover, because the so-called “swing voters” are the least attentive to politics, and most all over the ideological map (they are not consistent moderates or centrists), there is no reliable way to reach them on issues. Thus, Democrats should not worry so much about precise polling numbers, but instead focus on a broader big-picture story about their values, and highlight big bold progressive ideas that might break through the chatter.

I happily align myself with the critics of “popularism”, precisely for these reasons. There’s nothing wrong with saying and doing popular things, and as a general rule, governments should do what most citizens want. But it’s not a magic key for winning elections.

For those catching up: fusion voting refers to a system in which a candidate can win the support of more than one party – usually one major party and one “minor” party. Each party nominates the same candidate, and the candidate appears twice on the ballot under two distinct party labels. The votes for each candidate are tallied separately by party, and then added together to produce the ultimate outcome.

Fusion encourages parties to organize because it gives qualified parties a place on the ballot. This place on the ballot gives parties potential leverage, which they can use to bargain with major party candidates. It is this feature that makes fusion powerfully pro-more parties. A ballot line is power, and organizations and money are drawn to power like graduate students to a free lunch.

NY had vibrant Liberal and Conservative parties and it was not uncommon for Dem or Repub candidates to appear on those lines as well. The votes on those lines could be the margin of difference, and thus they tended to pull major party candidates AWAY from the center. I believe there were occasions, however, when a liberal Repub could win the Liberal Party line.

The make-up of the electorate means a 3rd choice like RFK would help Biden/Dems.

Also, IMO, you misrepresent Popularism. Popularism doesn't say "issues don't matter". It says to talk more about issues where your party is more popular.