The arc of history is squiggly - and four other takeaways from the 2024 election

This is a moment for imagination and big-picture thinking.

The day after an election is a day for sense-making. What happened? Why? What does it mean? What did we learn?

Well, here are my five takeaways, and some other thoughts…

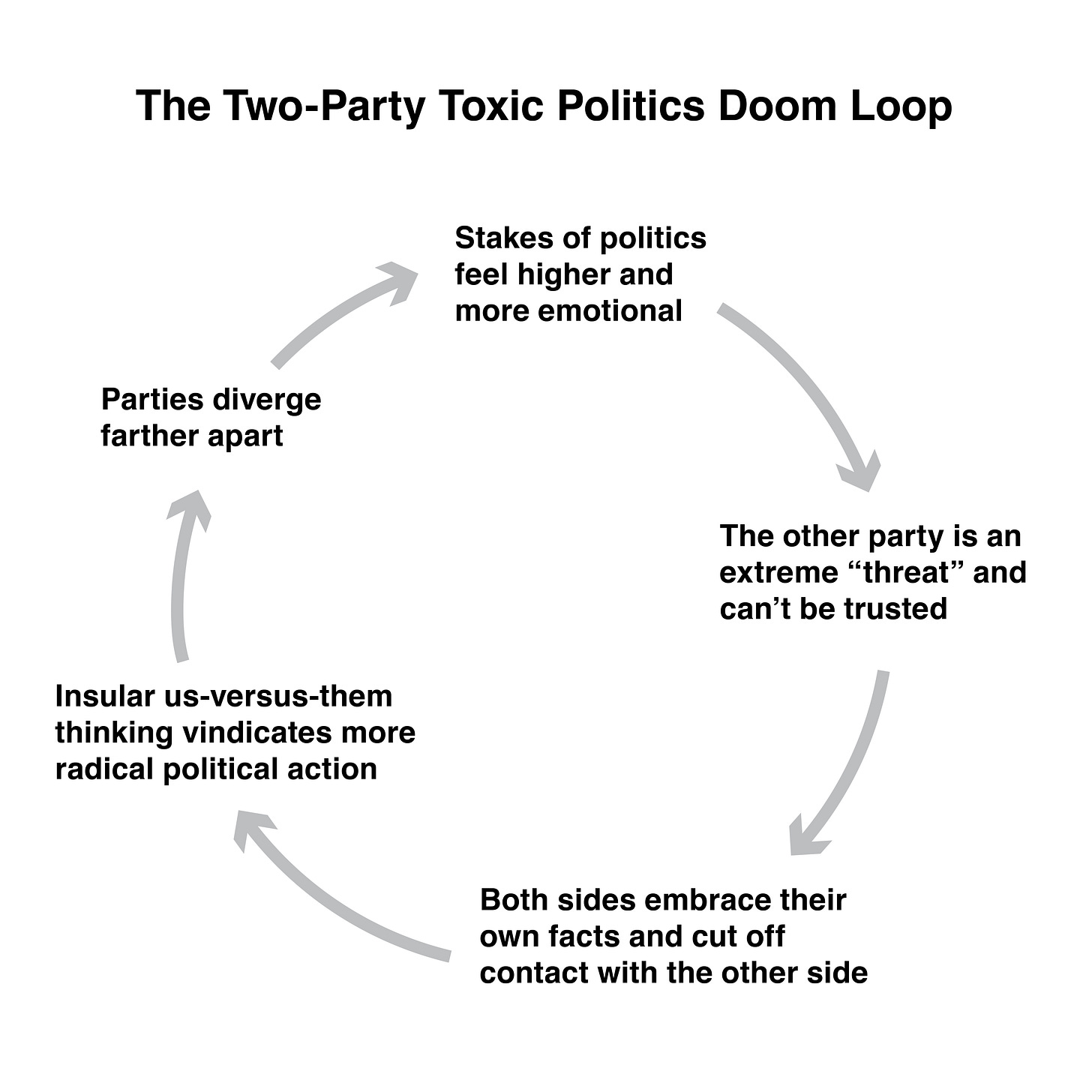

1. The Two-Party Doom Loop keeps getting doomier and loopier

This was an ugly campaign. The tone was very nasty. The threats and dehumanizations grew quite dark. This is the two-party doom loop in depressing motion: a vicious cycle of escalating rhetoric around continually high-stakes, narrowly-decided elections. As parties become more polarized, they compromise less and demonize more. It only gets worse and worse.

This self-reinforcing logic cuts at the foundational core of the democratic bargain — mutual toleration and forbearance. I only see it getting worse under a second Trump administration, which promises to be even more combative and vindictive.

Authoritarian leaders benefit from polarizing conflict. The ruthless us-versus-them dynamic gives them power to fight “the enemy within.”

The conflict is only going to grow more intense. Doomier and loopier, I often find myself thinking. This election did not reveal any off-ramps.

This makes me sick. It is like being on the scariest roller coaster ever and not being able to get off.

2. The anti-system vibes remain strong — and bad for incumbents.

Americans are in a sour mood and have been for a while. Overwhelming majorities report feeling dissatisfied with the way things are going in this country. For the last few years, the share of Americans feeling satisfied has hovered around 20 percent.

Such persistent dissatisfaction does not help incumbents. As I wrote earlier this year, no national political figure is viewed favorably. Incumbency, once an advantage in politics, is now a liability. Every election is now a “change” election.

This rumbling anti-incumbent dissatisfaction appears to be a global phenomenon, across democracies. We are in a kind of era of discontent. But this discontent seems especially pronounced in the United States. More than two-thirds of Americans think “the system” needs to change.

Harris at times tried to pitch her campaign as a “fresh start.” But ultimately she fell back on a campaign of continuity and defending the (distrusted) institutions. As the sitting vice-president, she really had no other choice.

The big problem is that when voters are unhappy with the status quo, they only have one other choice. If that choice happens to be an authoritarian, then voters who just want “change” may wind up with fascism.

3. Complicated, incremental electoral reform is not a winning path out of the doom loop

In six states plus the District of Columbia, voters had the option to open up their party primaries, adopt ranked-choice voting, or both, via ballot initiative. In one state, Alaska, voters were asked whether to preserve their reform.

Only Washington, DC voted in favor of open primaries and ranked-choice voting.

As an electoral reform nerd, this round-the-board rejection of primary and RCV reform was the biggest shock of the night. I had expected reform to pass in at least Oregon and Colorado, and possibly Nevada.

So what happened? Let me break it down…

In four states, the open primaries and ranked-choice voting initiatives were yoked together into one initiative.

In Colorado, voters rejected Proposition 131, which would have moved the state to a top-4 “all candidate” primary and a ranked-choice voting election. (The vote was 55% No to 45% Yes)

In Nevada, voters rejected the same proposition (but with a top-5 primary), by a similar margin (54% No to 46% Yes)

In Idaho, voters rejected their version of the measure even more overwhelmingly — 69% to 31%.

In Alaska, voters were deciding whether to keep their Top 4 plus ranked choice voting system, which they had approved narrowly in 2020 (when it was paired with a provision to eliminate dark money). The Alaska repeal effort appears to have narrowly succeeded, thus ending Alaska’s short-lived experiment with open primaries and RCV.

Only in my super-liberal home city of Washington DC did an RCV + semi-open primaries initiative (Initiative 83) pass.

In other states, ranked-choice voting or RCV were on the ballot separately.

In Oregon, voters rejected a standalone ranked-choice voting proposition (60% No to 40% Yes).

In Arizona, voters rejected Proposition 140, to create a single all-candidate “open primary” by a similar margin (59% No to 41% Yes)

In Montana, voters considered two separate initiatives (CI-126 - to create a single all-candidate “open primary”, like Arizona) and (CI-127 - to require a majority winner.). Voters decisively opposed CI-127, but as of this writing, they have only narrowly opposed CI-126, which remains too close to call.

Finally, South Dakota decisively rejected a “Top 2” primary reform (modeled on California and Washington), 68% against to 32% in support.

Frankly, I think voters made the right choices in all these places, even if they didn’t always do it for the right reasons.

To me, the open primaries + RCV combo (often billed as “Final Four Voting” or “Final Five Voting”) only further weaken parties (by pushing parties further out of the business of nomination). My view has long been that we need to build healthier and stronger parties. And that starts with giving parties more control over their nominating process, rather than allowing any schmuck to claim the legitimating label. These reforms would have moved us further in the wrong direction.

This combination also adds confusion and complexity to elections (making life difficult for already over-taxed election administrators). And making elections “nonpartisan” increases campaign costs and makes money even more important. This benefits wealthy candidates and donors even more than the existing system. The United States already has the most “open” primaries of any democracy in the world. Only in the United States can you register (for free!) as a member of a party and get to choose that party’s nominee.

I think there is a better direction for reform. Combining fusion voting for single-winner elections with party-list proportional representation for multi-winner elections. This straightforward solution addresses the core problems voters care about: lack of choices, gerrymandering, lack of competition, etc., with a single transformative sweep.

And yes, I understood the case many made behind the smaller changes: Get some wins, build momentum, get people comfortable with the idea of electoral reform.

Given these overwhelming losses, it’s time to reconsider that strategy.

Still: Why did these reforms fail so badly and decisively, across the board? Honestly, I’m surprised. My theory is that these reforms fell into a dead zone where they were not transformative enough to excite and energize voters who want big change, while simultaneously provoking a reflexive status quo bias against the added complexity. It also didn’t help that election administrators set off alarms about implementation.

Hopefully, the overwhelming failure of these reforms will spur a strategic rethink in the electoral reform community. It’s now time to focus on reforms that support stronger, healthier parties — and more than two of them!

4. Your donations to the campaigns were (overwhelmingly) wasted. And maybe even counter-productive.

The campaigns begged for and received billions of dollars of your money this cycle. Upwards of $16 billion. The presidential campaigns accounted for almost $4 billion of that. Most of that money went to all that annoying advertising. The Harris campaign outspent the Trump campaign. But Trump won.

Did any of that money make a difference? Probably not. I wrote a longer piece here skewering the campaign fundraising-consulting industrial complex (“The presidential campaigns don’t need your $5: And the more they devote themselves to fundraising and advertising, the more broke our democracy gets”)

My basic point was that once a campaign gets beyond a certain threshold, extra money becomes pointless. Perhaps even counter-productive. Yet, the campaigns keep asking for the money. They ask, because campaign consultants who run campaigns get very rich making and producing ads. Broadcast and especially also social media companies get very rich. But not only are these constant fundraising asks and campaign ads annoying. They are also overwhelmingly negative and anxiety-inducing. All this is very bad for our democracy. It probably makes the doom loop even worse.

Hopefully, we can spent some of that money elsewhere next time.

5. The arc of history is squiggly

We like to think there is some linear progress to history. But history is full of ups and downs. History is a sine wave. The arc of history is squiggly.

I take some comfort in this.

And often a “down” portends a future “up”

In my previous post here ("Perfectly Balanced, Totally Unstable: The dangerous strangeness of our perennially too-close-for-comfort elections”) , I argued that sometimes, when a system gets so FUBAR, sometimes collapse is necessary for renewal.

As I wrote:

My readings into complex systems (and history) point to an unfortunate pattern: sometimes collapse is necessary for renewal.

This idea goes against our instincts for control. But there it is.

Take forest management. Turns out, small fires are vital to a forest's long-term resilience. These small fires clear out accumulated fuel, make space for new growth, and bring nutrients back into the soil. Without them, tall trees crowd out everything else, making the whole forest vulnerable to devastating wildfires. ..

Complex systems can appear hopelessly rigid right before transformation. Yet beneath seemingly calcified patterns, the potential for renewal often lies dormant. Consider again our forest management analogy: After decades of fire suppression, forests don't just contain accumulated fuel—they also harbor dormant seeds awaiting an opportunity.

So that is perhaps the silver lining — sometimes things need to get worse before they can get better. But I’ll admit that’s not much silver right now.

Now what? Maybe something new?

I hope this moment is generative. I hope it creates space for some new ways of thinking about our political moment and the prospects for reform and renewal.

I hope it becomes clearer that we need a much bolder and ambitious vision for democracy reform. I eagerly offer my More Parties, Better Parties vision, built around both the structural reforms of proportional representation and fusion voting and a vision of political parties as genuine intermediary institutions, connecting citizens and government. Let’s discuss

I also take encouragement from the surprise performance of Independent Nebraska Senate Candidate Dan Osborn. He didn’t win. But he made a Senate race in solidly Republican Nebraska highly competitive. He did so by running as a working-class economic populist without the burden of the Democratic Party label. He even talked about the Two-Party Doom Loop!

Given how toxic the Democratic Party brand is in so many parts of the country, I really hope we see more Osborn-style candidacies. Otherwise, the Senate will likely stay in Republican control for a long time to come.

What I’m worried about

But I also have some real worries, beyond the obvious ones about how destructive and dangerous a second Trump administration will be (you can read about that on every liberal website).

I worry that Democrats will spend too much time playing counterfactual blame games now (what if Biden had dropped out earlier? What if Harris had picked Shapiro instead of Walz? What if Harris had settled on a campaign slogan?). I worry that Democrats will finger external factors like foreign interference, misinformation, or Elon Musk, rather than confronting the need for fundamental change. This blame-shifting serves mainly to exonerate current leadership. Real leadership means admitting when you’ve made a mistake and when it’s time to change.

I also worry that Democrats will just simply revert to counting on Trump and Republicans to over-reach and for thermostatic public opinion to predictably turn against Trump and deliver a repeat of 2018 and 2020. It may work out that way. But it may not.

We need a moment of genuine transformation

My bottom line is that our current political arrangement is only growing more unsustainable. Incremental reform, blame-gaming, and business-as-usual are not acceptable responses. To renew and revive the American experiment in collective self-governance, we need something more visionary and more transformative. This is a moment for imagination and big-picture thinking.

Hi Lee, big fan of your work! But if RCV is too confusing for voters, then why wouldn't "combining fusion voting for single-winner elections with party-list proportional representation for multi-winner elections" also be too confusing for workers?

Interesting read. Specifically, what would be “something more visionary and more transformative”?