How fusion voting builds the new parties that can break the two-party doom loop

Some reforms just rearrange the gridlock. This one unlocks the pieces that matter.

If you’ve been following the debates around electoral reform, you’ve probably noticed something confusing. Reform keeps spreading. But our politics keeps getting more dysfunctional.

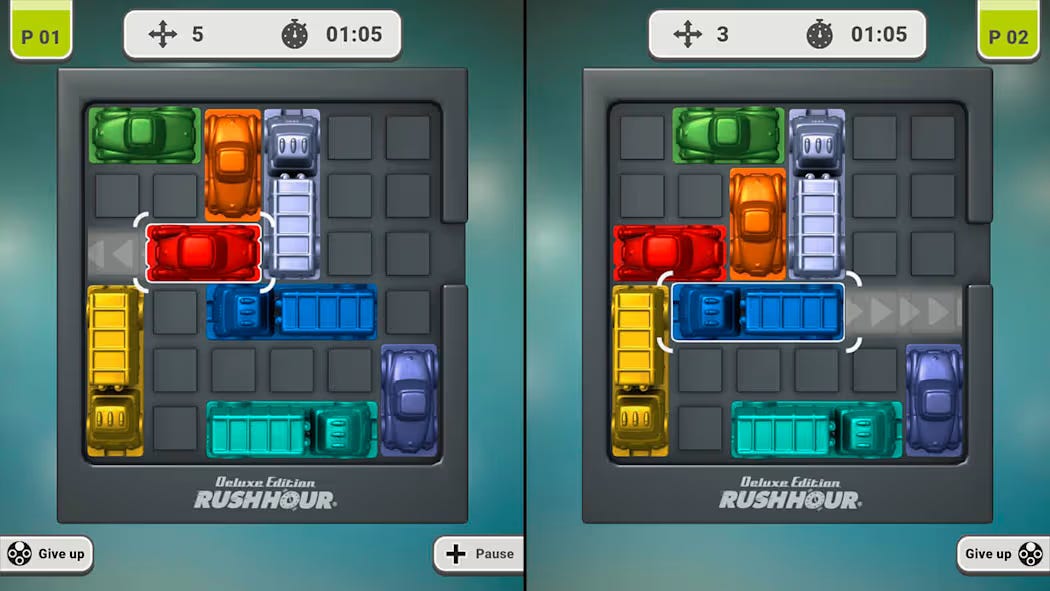

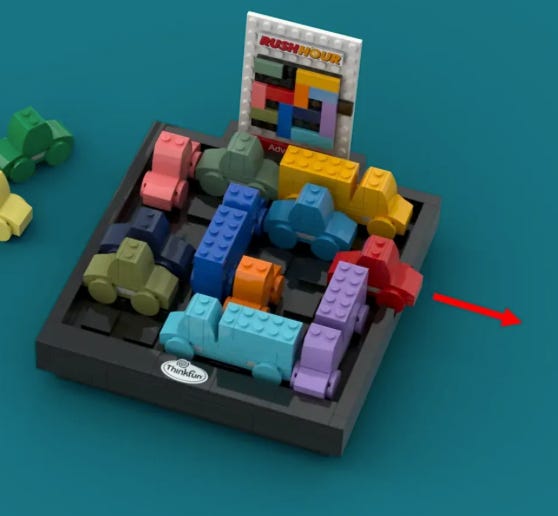

There’s a kids’ puzzle game called Rush Hour that helps explain why.

The goal of the game is to guide a red plastic car out of a parking lot. But that red car is jammed in pretty good. A bunch of other plastic cars and trucks block the way.

When my kids first played this game, they started moving everything haphazardly, eager just to see some motion. Any motion feels like progress. But not all motion actually is progress. Some motion is just moving things back and forth pointlessly until the kids finally give up, throw a tantrum, and elect an authoritarian president who channels their rage.

(Just kidding. Kids can’t vote. But frustrated adults behaving like tyrannical children sure can.)

You solve the puzzle by moving the cars and trucks in the correct order. Sometimes the puzzles are not immediately intuitive. The pieces you can move immediately are not always the right pieces to move unless you enjoy pointless motion.

This puzzle game came to mind when I read Protect Democracy’s important new report, Fusion Voting as a Pathway to Proportional Representation, by Deborah Apau and Jennifer Dresden.

The report is great, but if you want a shorter, more accessible version of it, I recommend Jennifer’s summary post at Protect Democracy’s excellent substack, If You can Keep It. I’ll cover some highlights here, but Jennifer’s post (A practical path to ending the two-party system: Why allowing multiple nominations is the first step to multiple parties) is the best single summary of her report.

As readers of this substack know, I see multiparty proportional representation as the most important reform necessary to break America’s destructive two-party doom loop, which remains on magnificent, disheartening daily display. Despite my tireless epistolary advocacy, we remain trapped in zero-sum winner-take-all trench warfare – a product of our antiquated system of single-winner plurality elections combined with today’s highly nationalized and geographically sorted politics.

But transitioning to full multiparty proportional representation from a winner-take-all two-party system is a big transition. Our proverbial plastic red car of the more fluid, dynamic, responsive politics I believe vibrant multipartyism could create is currently wedged in, good and hard.

But what comes first?

Theories abound. But in my opinion, most of the theories involve pointless motion. Some laws may be easier to change than others. But we should never mistake mere change for actual progress. Progress gets us closer to a desired goal. Change is, well, just change for the sake of change. Not progress.

The Protect Democracy report argues fusion voting is the smartest strategic move that frees up the key pieces, thus opening space for real movement. And I agree.

That’s because fusion voting does something that other reforms don’t: it builds new parties. These parties can then build the negotiating power to pursue proportional representation and to bring more voters on board as the party system opens up.

And for those new to fusion voting, it is and has long been legal in Connecticut and New York. Some may have noticed that Zohran Mamdani was listed twice on the New York City ballot, once under the Democratic Party, and separately under the Working Families Party.

Elon Musk, ever the half-wit with the $44B personal megaphone formerly known as Twitter, certainly noticed. And confused, he declared it a fraud. It was not, of course. It was just legal cross-endorsement, working according to the rules. Thanks to fusion voting, New York has viable and active minor parties.

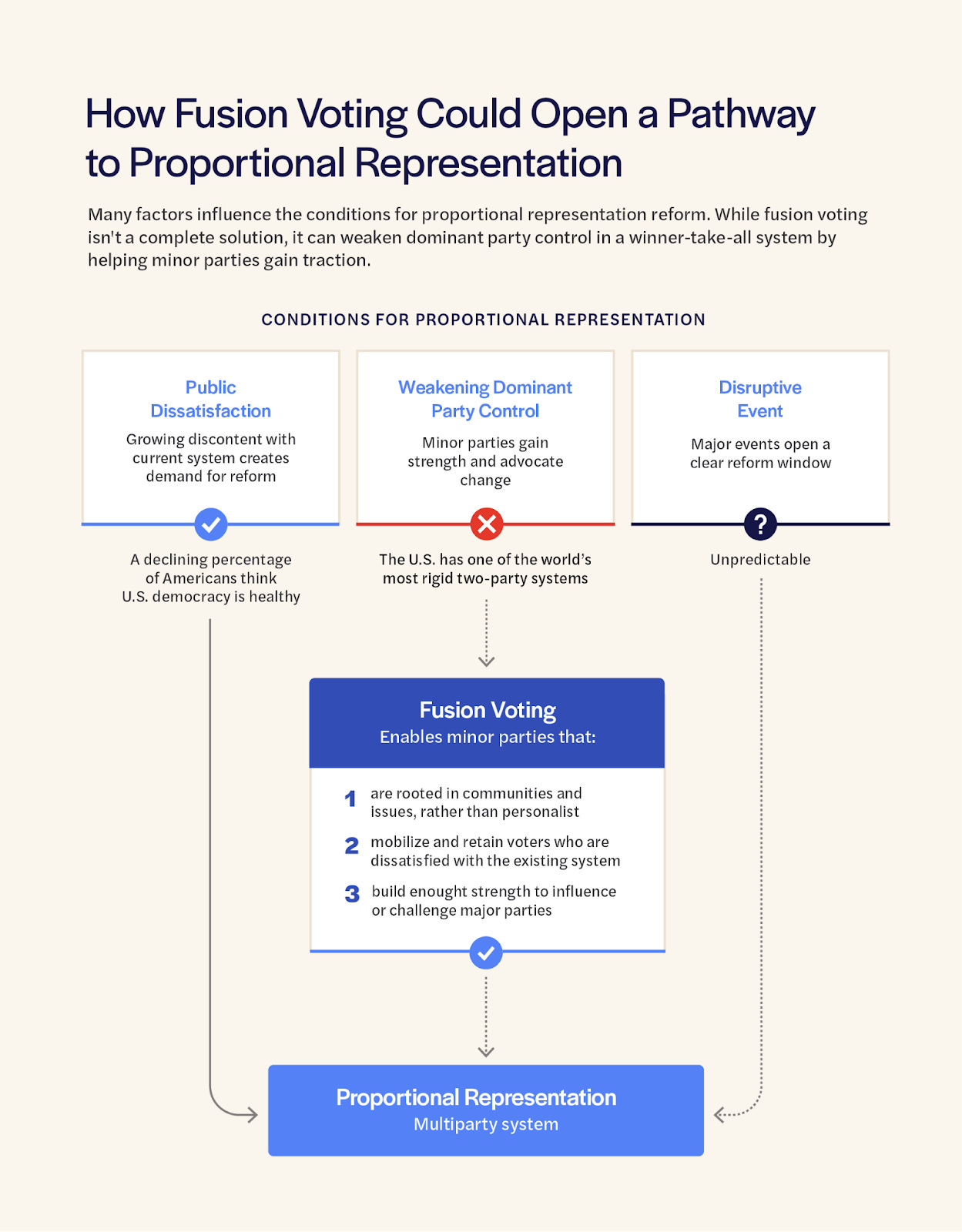

How winner-take-all systems change - the holy trinity of circumstances

The Protect Democracy report looks historically at other countries that have adopted PR systems and asks: what conditions bring about change in failing winner-take-all systems? Three key factors emerge.

(1) public discontent with the shortcomings of winner-take-all systems;

(2) a weakening of dominant parties’ control over the political system; and

(3) a disruptive event or shock that creates an opening for reform.

In fact, Protect Democracy made this handy graphic to summarize their theory.

First: Public discontent with the existing system.

When enough voters believe the current structure is failing them, change becomes possible. By this measure, America is ready and primed for the climb.

Discontent with our current system is the new national pastime. The two-party doom loop is becoming more and more obvious, even to casual observers. Almost eight in ten Americans think our country is in a political crisis. Almost that many say that our system either needs major changes (52%) or complete reform (24%).

As the Fusion as a Pathway to Proportional Representation report notes, winner-take-all systems are “particularly vulnerable” to demands for reform when “chronic disadvantage” translates into “tangible disparities in economic, social, and political outcomes.”

Second: Weakening of dominant party control.

This is the condition the report emphasizes most: “The presence of popular minor parties often plays a pivotal role in driving the change from winner-take-all to proportional systems.” When major parties lose their grip, space opens for new parties to form and compete.

Both Republican and Democratic coalitions certainly show signs of fracture—independent voters growing, party switchers increasing, intra-party warfare intensifying.

But new minor parties don’t just happen spontaneously. Change requires organizational infrastructure, which requires electoral rules to challenge major party dominance. New minor parties need ballot access, resources, and a legitimate way to challenge major party dominance. As the report notes:

“Minor or emerging parties are often critical agents in creating pressure for change, but the United States lacks a meaningful multiparty system. Yet this was not always so. Historically, much of the country had robust minor parties, thanks in part to electoral fusion—a practice where more than one party can nominate the same candidate. Today, the United States has lost its multiparty system in large part because its laws and practices, including widespread bans on electoral fusion, make it extremely difficult for minor parties to survive and grow.”

Third: A disruptive shock.

Some crisis or triggering event that breaks the system open—an economic collapse, a war, a legitimacy crisis. The report examined Italy’s post-WWII reconstruction, South Africa’s end of apartheid, New Zealand’s spurious majorities crisis (the party with fewer votes kept winning legislative majorities – a possibility in plurality voting systems, which New Zealand used until it adopted proportional representation in 1996). These shocks “serve as catalysts for larger-scale electoral reforms, including the adoption of PR.”

We can’t predict when such a shock will happen. Nor can we manufacture it on demand. But it sure feels like we are getting close. Sometimes moments of crisis shock a political system into reform and renewal. But sometimes they don’t. Sometimes they just cause collapse.

Obviously, we have condition one. Public frustration is measurable and growing. Condition three is outside our control—shocks happen when they happen. Though it sure feels like we may be approaching one. Or perhaps we are in the middle of one.

But condition two—building meaningful new party organizations —is something we can do right now.

Some might argue that we do have meaningful third parties – The Libertarian Party is ballot-qualified in 38 states; The Green Party is qualified in 23 states. But these parties do not build meaningful power because they run stand-alone candidates that rarely win anything more than a city council seat here and there. Mostly, they just organize protest votes. They remain pure – speaking truth to power, and thus unable to build any power on their own.

Fusion voting makes a different kind of minor party possible. Rather than act as spoilers or wasted votes, minor parties operating in a fusion system can build durable organizations, develop voter bases, and accumulate negotiating power by selectively cross-endorsing major party candidates.

As the Protect Democracy report argues, fusion “channels the fundamentally candidate-centric nature of our elections through parties, working within the system to create space for minor parties to build support and exercise influence.” Minor parties can become “leading advocates for adopting proportional representation.” They help create the pressure that makes change both more likely, and more likely to succeed .

It is true that both Canada and the United Kingdom remain first-past-the-post systems despite minor parties. But the minor parties there do advocate for proportional representation—and consistently. Canada’s NDP has pushed for PR since 2003. The Canadian Greens for twenty years. The UK’s Liberal Democrats have long supported PR, joined by the Scottish National Party, Plaid Cymru, and even right-wing Reform UK. And major parties occasionally promise reform too—most recently, Justin Trudeau’s Liberals in 2015. In the UK, PR remains on the political agenda.

How fusion bootstraps organizational capacity with a ballot line and vote totals

Fusion allows multiple parties to nominate the same candidate, with each party maintaining its own ballot line. Voters choose which party line to use. All votes count toward the candidate’s total, but the vote totals for each party line remain visible and matter independently.

This structure encourages party-building through three features: First, the ballot line becomes a valuable asset that requires gatekeeping; Second, vote totals create measurable leverage that requires consistent delivery; and Third, the party’s brand appears on every ballot which requires quality control. In short: You can’t let just anyone use your line, you can’t negotiate without sustained performance, and you can’t maintain credibility without organizational capacity to enforce standards.

This creates a bootstrapping dynamic: cross-endorsements generate measurable vote totals, vote totals create leverage with winning candidates, leverage extracts commitments and resources, resources build stronger organization, stronger organization delivers votes more reliably, reliable delivery increases leverage. The positive loop reinforces itself—but only if the party maintains the organizational capacity to deliver consistently across cycles. Temporary campaigns and candidacies can’t do this. Only sustained institutions can.

Where other reforms fall short: they don’t build new parties

Maine approved RCV in 2016, and began using it in 2018. Nearly a decade later, zero new parties have run candidates under RCV elections. What Maine got instead was a few more independent candidates—temporary campaigns. You can’t build sustained pressure for systemic reform around candidates who come and go, without any organizational capacity or commitment.

Similarly, many argue for “open primaries.” Open primaries come in several flavors, from just allowing independents to vote in party primaries (most common) to two-round, all-candidate systems like California, Washington, and Alaska.

But California and Washington have not produced new parties with their top-two systems. If anything, they’ve made it harder for minor parties to compete by limiting the general election ballots to just two spots. This is why minor parties have sued to declare the top-two system unconstitutional, because it effectively keeps minor parties from appearing on the general election ballot.

Alaska’s top-four system has yielded a slight uptick in political independents, sure. But again: they are Independents. They are not building any new organization. Maybe they will. But not yet.

Both of these reforms — ranked-choice voting and open primaries — certainly do lower barriers for individual candidates without requiring sustained infrastructure. A candidate can run as an independent. But then that Independent disappears when the cycle ends, leaving nothing behind to build longer-term power for voters who want to organize an alternative to the two dominant parties.

To me, both of these reforms feel a bit like moving around the un-restrained plastic cars on the Rush Hour board. Yes, they feel achievable. And so some reform supporters try to achieve them. But even where they have been implemented, they don’t change much. My deep dives into both primary reform and ranked-choice voting convinced me these reforms were too marginal to have any positive impact.

And maybe these reforms are actually not as achievable as some believe. After all, in 2024, voters in Oregon rejected a statewide ranked-choice voting ballot initiative, voters in South Dakota rejected a top-two ballot measure, voters in Montana and Arizona rejected open primaries ballot initiatives, and voters in Colorado, Nevada, and Idaho rejected adopting Alaska’s top-four system combining an all-candidate primary with general election voting. And Alaska nearly voted to end its experiment in 2024, and will likely hold another ballot initiative to repeal the system in 2026.

(Maybe it only feels easy to achieve these reforms because advocates can raise money from funders to run these initiatives?)

Faction building is also a smart move. Especially when paired with fusion voting.

Others argue for more informal faction building within the major parties. This comes much closer to a smart strategic move in unlocking genuine dynamic multi-party democracy.

But there is just one limit to the faction-building strategy: within the existing voting rules, factions do not have ballot lines. This makes them much weaker — they cannot distinguish themselves from the major party, nor can they point to their numeric support as they could if fusion were legal. Instead, they just blend in. And in our current highly nationalized politics, in which individual candidates struggle mightily against the weight of national partisan identity, how do they signal they are different from their party’s president? Not easily. Perhaps not at all. A faction with a ballot line would be much more powerful than a faction without a ballot line.

Organizing factions is definitely an important strategic step solving our doom loop puzzle. I think investing in factions is worthwhile, and would like to see more of it! Faction-building is a far better investment than another attempt to pass open primaries or top-two elections or ranked-choice voting. But without the next step of a ballot line, factions are blocked from playing a more visible and more meaningful role.

However, a combined strategy of faction-organizing and smart party-centric electoral reform would be a very powerful combination!

Fusion voting for single-winner elections is the perfect complement to proportional representation for multi-winner elections

Let’s say we get proportional representation. Amazing! But…it only works for potential multi-seat elections. Some elections are inherently single-winner — U.S. Senate, state governor, city mayor. And of course, there can only be one president. These offices will remain winner-take-all, barring improbable constitutional changes.1

This creates a challenge for minor parties. Let’s imagine a state passes proportional representation for its state legislature. What happens to the statewide elections — governor, secretary of state, attorney general? Do all parties run candidates? A better system would be to allow multiple parties to fuse on a shared candidate. This encourages them to organize a pre-electoral coalition, which would make governing clearer and easier, should their coalition win a majority.

Moreover, the 1967 Uniform Congressional District Act currently prevents states from using proportional representation for U.S. House elections. States can reform their own legislatures, but they’re stuck with winner-take-all for federal races. Fusion can allow the minor parties to play a productive role in federal elections for House and Senate through cross-nomination. And even if Congress passes a law mandating proportional representation for U.S. House elections, senate and presidential elections will still be single-winner affairs.

Proportional representation and fusion voting work well together. They are mutually beneficial and mutually reinforcing. PR creates multiparty legislatures. Fusion keeps those parties viable in the single-winner elections that will always exist. Together, they create sustainable multiparty democracy.

New party building is hard work. It’s more than just a ballot line. It’s a serious investment in organizing. Fusion ups the visibility of minor parties in the single-winner elections that command the most attention -- President, Governor, Senate, Mayor. With the power of a ballot-line endorsement in these elections, a new party gains name recognition and supporters. This support then reinforces and complements the support for new parties as they run their own candidates in proportional elections, ideally for the U.S. House, and for state legislative elections

We need more parties, not more candidates. Or, Why better merging doesn’t fix an overcrowded two-lane highway

If you’ll indulge me in taking the Rush Hour puzzle from a toy model into a full-fledged traffic metaphor, a useful framework emerges.

Think of it this way: America’s political system is an overcrowded two-lane highway where traffic has ground to a near halt of aggressive inching and aggravated honking. It’s way beyond its carrying capacity, and it’s breaking down under the weight of constant traffic. There’s just not enough space for all the perspectives.

And stop and go traffic turns everyone into an asshole, basically.

What are some solutions for managing traffic? One is to build some new roads, to create more ways to get from place to place. Another is to create HOV (high occupancy vehicle lanes) that encourage carpooling, so there are fewer individual cars. All of these widen the pluralism of the road, and allow traffic to flow more freely.

In this metaphor, think of proportional representation as adding more roads, so there are more paths to power, and if one road gets jammed, a new road is possible. Think of fusion as opening up HOV lanes to encourage carpooling. Multiple parties endorse the same candidate. The Working Families Party coordinates pickups, recruits voters, delivers numbers — helps the Democratic Party get there a little faster. The Conservative Party might do the same for the Republican Party. A Moderate Party could also recruit some new carpoolers, which could help moderates of either major party.

The new HOV lane opens up, and organizing matters more. Recruit more people to your carpool, and get there first — win the election!

And remember: The winners get to decide whether new roads get built in the future — and what they look like. So, if you can’t carve out your own lane, better to join a carpool!

By contrast, ranked-choice voting and open primaries are like on-ramp solutions. They are trying to figure out how to get more traffic on the existing narrow roads. Sure, they might offer better yield signs, smoother merge geometry. But that assumes potential room for them on the existing road. And there’s not.

These individual candidates hoping to get on the highway without being part of the existing partisan flow of traffic? They sit at those on-ramps waiting for an opening that doesn’t come. If you’ve ever tried to merge onto an overcrowded and stopped highway, you’ll understand. Who is going to let you in?

The major parties won’t voluntarily cede power. But they want to win elections too. So if carpooling helps them get across the finish line first, maybe the HOV lane (fusion in this metaphor) is a pretty smart idea for the party that can build the bigger coalition.

Democracy reform is a hard puzzle, but solutions exist

As the Protect Democracy report makes clear, the path to proportional representation requires three conditions: public discontent with winner-take-all, weakening of dominant party control, and a disruptive shock. We have the first. The third will come—we can’t control when. The second we can build.

Right now, fusion voting is the most powerful way to start that building. Create new party organizations with ballot lines that give them reasons to build something more than a one-off campaign. When the shock arrives, these parties can negotiate systemic reform.

Back to that parking lot puzzle. It’s a puzzle. But there is a logic to the puzzle. When the pieces are all jammed, moving the loosest piece can feel like progress. But motion for the sake of motion is just silly.

Given our current jam, re-legalizing fusion voting is the smart next move. It’s the move that frees up other smart moves.

Finally, while we’re on the topic of electoral reform… a few other news nuggets

American Bar Association Task Force on American Democracy recommends fusion voting

Recently, the American Bar Association Task Force on American Democracy released its report.

I’ll turn it over here to ABA task force members William Kristol and Tom Rogers, who wrote about their recommendation in Newsweek:

The ABA Task Force’s forthcoming final report will offer many excellent suggestions on steps to bolster it. Among the recommendations under consideration, there is one that we especially wish to shine a light on: multi-party nomination, or “fusion” voting…

For nearly a century, fusion was legal and common in every state. It allowed new ideas, new leaders, and new parties to emerge. Abolitionists, farmers, emancipated Blacks, mechanics, prohibitionists, and populists all used fusion voting during the 19th century to make sure that their voices were heard by their fellow citizens as well as the leaders of this vast, diverse nation.

But politics has changed, and not for the better. The vitality and flexibility of a multi-party system has been replaced by the brittleness and anger of a hyper-partisan, polarized two-party “doom loop.” Until the 1990s, our two-party system was much less polarized and much more local. There were conservatives, moderates, and liberals in the Republican and Democratic parties, which facilitated cross-partisan cooperation and deal-making. Today, politics is deeply tribal and fully national, and it is very rare for a member of Congress to cross party lines. This hyper-polarization is not just a Congressional problem; it afflicts most state legislatures too. Today the incentives flow towards conflict rather than collaboration, stymying effective governance and making more Americans question whether democracy is working.

Unfortunately, the more people get turned off by the choices served up by our two-party system, the more they may find strongmen and demagogues appealing. Ending the ban on fusion voting would enable people in the political center to build their own political home and to pull the other parties away from their extremes. In New York City, for example, centrist candidate Mike Bloomberg was able to get elected mayor in part because the Independence Party allowed voters a way to back him that did not rely on the two-party framework…

As we write, there is litigation underway in New Jersey, Kansas, and Wisconsin to have these bans declared unconstitutional under their respective state constitutions. The plaintiffs are the New Jersey Moderate, United Kansas, and United Wisconsin parties.

Citizens and leaders who cherish self-government and the rule of law should welcome the forthcoming recommendations from the ABA Task Force. It’s not too late to restore confidence in our democracy.

And while we’re on the topic of the ABA Task Force, might as well also lift up the brief I wrote for the ABA Task Force in support of “Reviving the American Tradition of Fusion Voting,” with Tabatha Abu El-Haj, and Beau Tremitiere

University of Wisconsin-Madison Law School holds a conference on fusion voting.

Last week, I participated in a conference at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Law School on fusion voting. It was a great line-up of thinkers and do-ers, gathered to discuss fusion voting in light of a recent lawsuit to re-legalize fusion voting in Wisconsin.

The Wisconsin Examiner wrote up the event. I also published an op-ed in support of fusion voting in the Madison State Journal, co-authored with University of Wisconsin political science professor Barry Burden.

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (AAAS) releases a new report in support of proportional representation.

And while we’re on the topic of esteemed American institutions considering reform, here’s another report, this one from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, as part of the academy’s Our Common Purpose project: Expanding Representation: Reinventing Congress for the 21st Century

The report details various options for proportional representation in the American context. As the report concludes: “We recognize that implementing these recommendations would constitute a major change in a nation where single-seat, winner-take-all elections are a firmly entrenched part of our political culture. But we maintain that the benefits—improved representation, better governance, and reduced polarization—make this path well worth considering. American voters are open to change; the time has come for our policymakers to deliver it.”

I’m proud to say I served on the working group for this report, and I contributed to writing the report, along with many others.

The American people support proportional representation, too.

Finally, I want to highlight this data point from G. Elliott Morris’s excellent substack, Strength in Numbers. Morris reports that: “48% of adults say they would support a system where states are required to assign seats in the U.S. House in proportion to the number of votes won statewide, while 19% are opposed. 32% of respondents said “don’t know.” Proportional representation is popular!

Though perhaps some states and certainly some cities could more easily shift to parliamentary-style governments, in which the legislature would choose the executive.

I see the potential benefits of this strategy. It acclimates the electorate to differentiating between ballot lines, legislative factions, and party organizations on one hand, and candidates on the other. And in a way that they can see the effects (in official ballot documents, in messaging, in organizational activity, etc). It cultivates a prerequisite change in culture, whereas so many reform efforts seek to impose a top down solution, which if we could do, we certainly wouldn’t impose some half-measure that nibbles around the edges of the problem.

3 seat PR with droop quota wd suffice for US house of Reps if we also introduced 1/3rd Reps. Then, if we used 3 seat PR with a hare quota for state reps elections, it wd likely trickle up to make the 3rd seat in natl reps elections become competitive.