How Democrats could win a shutdown fight, and why they won’t

Notes on a theory of strategic conflict.

It is 2025. America is falling into authoritarianism. And the Democratic Party does not have a strategic theory of political conflict.

A theory of attention is not a strategic theory of conflict.

A theory of moderation is not a strategic theory of conflict.

A strategic theory of conflict is about choosing the fight that brings the most people to your side.

A strategic theory of conflict is about starting new fights, not accepting old ones.

What do I mean? Well… let me explain.

One-dimensional pulling vs multidimensional spinning

Most political analysis treats politics like a tug-of-war along a single rope. Democrats on the left, Republicans on the right, independents in the middle.

The question becomes: Where exactly is the optimal position on this line? As if politics were a math problem with a single correct answer.

But what if politics isn't so neatly linear?

What if, instead of a single tug-of-war on solid ground, we imagine a playground spinner—one of those whirly platforms where the axis of rotation determines everything.

When it spins around "taxes versus spending," certain positions have leverage. When it rotates around "order versus chaos," completely different positions matter.

The platform can spin around corruption, immigration, crime, healthcare, democracy itself—each rotation has its own tilts and whirls.

Here's the thing: whoever controls the spin, controls the game. It's not about pulling harder. It’s about determining the master conflict that directs the spins.

When you're stuck fighting against the spin, you have two choices: keep pulling harder on a losing dimension, or grab the rails and shift the spin. Make politics rotate around corruption instead of immigration. Around oligarchy instead of bureaucracy. Around insider trading instead of insider pronouns.

So if choosing the dimension of spin matters most, why do Democrats keep accepting the dimensions chosen by Republicans?

Schattschneider and The Semi-Sovereign People

Here, I'm just restating some basic principles from one of my favorite books of political science, E.E. Schattschneider's classic, The Semi-Sovereign People: A Realist's View of Democracy in America (1960).

Last week, I published an essay on Vox applying Schattschneider's conflict theory to Democrats' contemporary messaging struggles. I argued that, "The Democrats don't have a messaging problem. They have a much bigger problem: They have accepted a losing political battle they never chose without even realizing it."

As I explained, over the past decade, Democrats accepted their role as defenders of the existing institutions, while Republicans claimed the existing institutions were corrupt, weak, and decaying. Democrats defended the status quo while Republicans raged against disorder and decline.

Unfortunately, defender of failing institutions has not been a winning dimension of conflict for Democrats.

And Democrats have failed to organize a new conflict to divide the electorate differently.

As Schattschneider wrote: "What happens in politics depends on the way in which people are divided into factions, parties, groups, classes. The outcome of the game of politics depends on which of a multitude of possible conflicts gains the dominant position."

Conflict organizes politics because conflict is interesting, and the most important political battle is always the battle over which battle matters most. Coalitions and majorities follow from the battle lines.

"The definition of the alternatives is the supreme instrument of power," Schattschneider argues. "He who determines what politics is about runs the country, because the definition of the alternatives is the choice of conflicts."

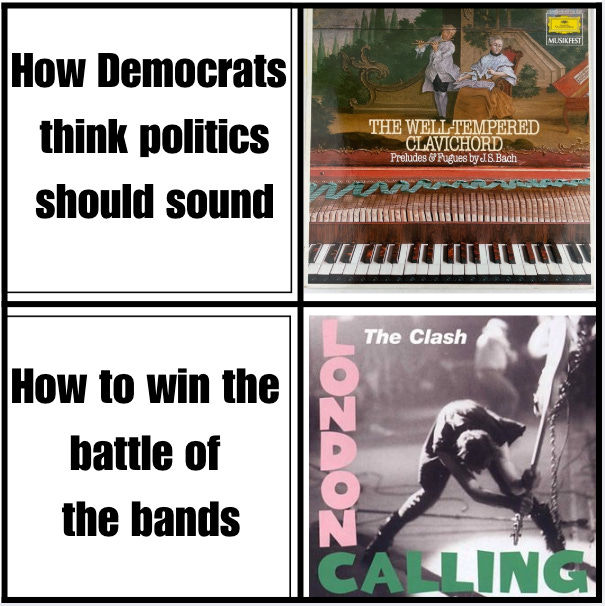

Without a theory of conflict, your messaging and mobilization theories amount to rehearsing your Bach fugues for a punk rock battle of the bands you didn’t choose to sign up for.

Let me offer a more mundane example of how the choice of conflicts shapes outcomes. As I wrote in my Vox piece:

When I want my kids to clean up, I don't ask whether they want to clean or not --- I ask whether they want to clean now or in five minutes. They always choose five minutes, having failed to recognize my displacement of the real conflict by my strategic definition of alternatives. They would make excellent Democratic campaign managers."

A theory of attention is not a strategic theory of conflict

The first flawed theory is that Democrats just need to get more attention. The argument goes something like this: In an age of fractured media, it is harder to reach people. And so Democrats need to do more to reach people.

Ezra Klein makes a version of this argument in his recent essay on the looming shutdown politics. As he writes (italics mine):

The case for a shutdown is this: A shutdown is an attentional event. It's an effort to turn the diffuse crisis of Trump's corrupting of the government into an acute crisis that the media, that the public, will actually pay attention to.

Right now, Democrats have no power, so no one cares what they have to say. A shutdown would make people listen.

But what if Democrats' problem isn't that nobody's listening—but that they have nothing new and exciting to say?

Indeed, a government shutdown is a focusing event. It is also potentially interesting because it is a high-stakes conflict.

And: Conflict is interesting.

However, Klein immediately recognizes the limits of a shutdown-as-attention-grabber strategy.

But then Democrats would have to actually win the argument. They would need to have an argument. They would need a clear set of demands that kept them on the right side of public opinion and dramatized what is happening to the country right now.

“They would need to have an argument.”

“They would need a clear set of demands”

Reader: They don't.

They have binders of expensive briefing memos on which messages poll better than others, what words to use and not use, and how to talk about the conflicts foisted upon them.

And yet, despite all that… the best they can do is re-word Trump's Big Beautiful Bill as Ugly instead of Beautiful. Brilliant plan, team! Just remember, though, kids... I'm rubber and you're glue, so everything you say bounces off me and sticks to you.

As Klein concludes: "Democratic leaders have had six months to come up with a plan. If there's a better plan than a shutdown, great. But if the plan is still nothing, then Democrats need new leaders."

Maybe Klein is right. Maybe Democrats need new leadership. But it's the easiest thing in the world to fire the coach.

Unfortunately, the problem is bigger: Democrats don't realize they're pulling against the rotation of politics. They think if they just get on more podcasts, get grippier messaging gloves, get more people—they'll win the tug of war. They won’t. They’ll just get dizzy trying.

At this point, Congressional Democrats may as well just fold. Then they should tell their unhappy activists if they want them to fight next time, they need a clear, singular demand.

But maybe it's not too late. There are still a few weeks.

So: What would picking a new fight actually look like? Let me illustrate how to actually tilt the political spinner.

Four ideas on how Democrats could use a shutdown fight

1. Corruption is spelled E-P-S-T-E-I-N

Why not start with corruption—the one issue where Democrats have ample ammunition but struggle to aim their fire? The simplest and most effective strategy would be the oldest move in the political playbook: the politics of scandal. There are so many egregious grifts this administration is engaged in.

But don't pick 100. Nobody can keep track of 100. Pick one. Just one. And make it stand in for everything.

And maybe just pick the one already getting the most attention, the one with the smiling photo of Jeffrey Epstein and Donald Trump, and make it stand for everything else. No government funding until the Epstein files are released! Simple demand. Pass the Epstein Files Transparency Act.

2. Fighting gerrymandering is fighting authoritarianism

A second fight Democrats could force is the fight over gerrymandering, which Republicans opened with their mid-decade redistricting of Texas.

Admittedly, both sides have been escalating this conflict for decades. But the mid-decade Texas gambit takes it two steps further.

Democrats have certainly been fighting back. But...the fighting fire with fire stuff is pure doom loop politics.

Maybe it's better to work to extinguish the fire altogether?

Democrats could take the high road here. Use their leverage to demand an alternative to partisan redistricting. Put Republicans on the defensive, rather than giving up your long-fought advantage as the high-ground party against gerrymandering.

The demand could be as simple as outlawing mid-decade redistricting. Better would be truly independent districting commissions. (Though such commissions have real limits. Trading off partisan fairness with electoral competition is not as easy as you might think if you are stuck with single-winner districts)

Even better: proportional representation to enshrine a system that actually does what everybody intuitively thinks a fair voting system should do: give parties electoral seats in proportion to the share of the votes they get!

But broaden it even further: Authoritarian regimes rig the rules to stay in power. And this is exactly what Republicans are trying to do. So, let’s make it impossible.

3. Crime is a real problem

Democrats could also use this moment to alter perceptions of their weaknesses.

Republicans clearly think crime in the cities is a good issue for Republicans. But is it?

What if Democrats offered a different solution to the crime issue? Something big, like a major investment in police forces (double the number of police, pay them more, train them more) and a major investment in community mentoring organizations to get troubled young men into support networks instead of prisons.

I haven't studied criminal justice deeply, but I know this: without an attention-grabbing alternative on urban crime, Democrats hand Republicans a permanent wedge issue. And arguing about whether crime is down or not is playing defense on their terrain. It is accepting your opponent's definition of the conflict rather than creating your own.

Crime may seem like a weak issue for Democrats. But a killer strategic move in politics is to take a weak issue and re-orient the conflict to make the other side’s strength their weakness.

4. Immigration is a real problem.

Similarly, immigration is right now a bad issue for Democrats. Could they flip it? Demand more immigration judges to process the backlog of cases. Demand a policy to prevent abuses by ICE. A secure border and human decency aren't mutually exclusive.

Again, I don't study immigration policy, but you can't simply ignore such a charged issue. You need to have a solution to what is obviously an extremely broken system.

Of course, Democrats have no interest in bringing up crime or immigration, because they have no plan to address them! So it goes.

Why healthcare is the wrong issue

Apparently, Democrats are contemplating a shutdown fight over healthcare. Or more specifically, their demands are to reverse Medicaid cuts and extend Affordable Care Act subsidies.

Way to go big, Democrats! Real punk rock move. (I’m kidding, of course)

"Healthcare is a clear red line," House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries said last week "We will not support a partisan Republican spending bill that guts health care away from the American people."

But unless Democrats are proposing a major reform to the healthcare system that cuts costs dramatically for most people, healthcare is not going to be a major electoral issue in the mid-terms. It's just not.

The share of people who depend on these subsidies is very small. The share of the electorate that depends on these subsidies is even smaller, since lower-income people vote at lower rates. The cuts are designed to not go into effect until after the mid-term.

As I explained in a previous post, arguing about healthcare cuts is a losing strategy for Democrats. The voters Democrats need to engage don't vote enough on these issues, and many don't vote at all.

If Democrats want to pick this fight, it will get very little attention, because it is the most predictable, familiar fight ever. There is nothing new, or surprising.

There is also no activist demand for healthcare. If Democratic leaders want to be in a bargaining position, they need to go to Republicans and say: "this is what my people demand. Maybe I can bargain with them, but only if you give me something."

Demanding attention without redefining conflict is pointless, and probably counterproductive: Look at us. We’re still the same clowns you remember! Only older.

Matt Glassman makes a compelling case against any shutdown, correctly noting that every strategic shutdown has failed to benefit the shutdown party. And he's right: they all failed.

But this perfectly illustrates my point: these shutdowns failed because they all fought on existing terrain. Gingrich fought Clinton about spending levels. Cruz fought Obama about program implementation. They made losing demands on overly-trod terrain.

Let’s move onto the moderation question. Same problematic one-dimensional thinking approach, different debate.

Moderation is also not a strategic theory of conflict

A second strategic debate within the Democratic coalition concerns "moderation." Put simply, the proposition is thus: Democrats should move closer to the political center in order to win elections.

But what is the political center?

Well, it depends on the issue, doesn't it?

This is why the issue of "moderation" is confusing.

Data nerds are currently brawling over whether "moderation" helps Democrats electorally by a few points or nothing at all— Lakshya Jain says it’s between 3-4 points, Elliott Morris says maybe 1-2, Nate Silver referees the methodology, Matt Yglesias says it's a net positive whatever the advantage,while Adam Bonica and Jake Grumbach show the whole debate rests on biased metrics (and thus, once you use the correct metrics, the supposed moderate bonus all but evaporates).

This is an extremely silly debate—an unresolvable argument about political strategy masquerading as a resolvable fight over measurement.

But it is also a debate that helpfully illustrates the failure of this kind of "thinking in inches" along a single dimension.

Yes, that single dimensional thinking…

Since the 1950s, political scientists have been developing and refining spatial models of politics. Most of these models are one-dimensional models.

These models have so colonized our political thinking that we intuitively think of politics as existing on a single left-right, liberal-conservative axis. We are trapped in the tug of war mentality.

In this model, the center (aka, the “median voter”) is purely relational.

The implied idea is that there are two competing governing philosophies at either end of the spectrum, and the middle exists in relation to those two philosophies. We even apply color to this spectrum now, from deep blue to deep red, with purple in the middle.

But of course, we all know that politics is not entirely one-dimensional. We know that many of us hold idiosyncratic views that don't entirely fit one party, and that there are still sometimes "odd bedfellows" coalitions that break traditional party lines. For example, sometimes Democrat Ron Wyden votes with Republicans Mike Lee and Rand Paul --- against everyone else in the Senate.

To measure "moderation," political scientists use various statistical techniques to reduce a high-dimensional political space onto a one-dimensional line.

At best, we can add a second dimension. But because printed paper and computer screens are only two-dimensional, we are limited in our visual representation capacity. And even in two dimensions, moderation is confusing when it is really the averaging out of more extreme positions across different dimensions.

The big problem is that you have to decide first, what data sources best describe this single dimension; and second, how to deal with data that doesn't fit neatly along that single dimension. There are various statistical techniques to accomplish this measurement. And as you might expect, if you use different tools to measure something, you will get different measurements.

This is a problem in measuring ideology. It is not something out there in the world that you can count, like votes or potato chips. It is a social construct, which depends on how we define it and choose to measure it.

And this is why academics and data nerds are constantly arguing. The "moderation" that gets you a one-point electoral boost is a slightly different construct than the "moderation" that gets you a three-point electoral boost.

This tyranny-of-small-differences misses Schattschneider's insight: the problem isn't where you stand on one dimension—it's who chose that dimension.

I get why we do it. Because otherwise, we'd have no way to model the political world. And it can be useful. But remember: models are always limited tools capturing partial reality at specific moments.

I am pro-models because they give us a way to understand otherwise confusing reality. But models are only useful if we are honest that they are indeed models, and that they leave important things out, and they make hidden assumptions.

And what any model of "moderation" leaves out is the higher-dimensional space of politics, which is where the most important changes happen. It also does not capture change over time very well.

Are liberals now actually the true conservatives, whereas conservatives are the radical nationalists? Things are shifting!

Conflict is not stable. Politics is defined by different conflicts at different times. And the substance of the conflict matters. It was not that long ago, 2012, when we had a presidential election about somewhat anodyne economic issues, the role of government in the economy, taxation, that kind of thing.

Certainly, it is possible to construct a relational mathematical measure of "moderation" that bridges 2012 and 2026. But substantively, what are we really measuring? Just think about the journey of Liz Cheney, who went from being very conservative to... what?

What is the moderate position on gerrymandering?

What is the moderate position on whether or not to release the Epstein files?

What is the moderate position on authoritarianism?

Both the attention theory and moderation theory share the same fundamental flaw: they accept the existing conflict terrain as given and static. The moderation data nerds and shutdown commentators are bringing the same one-dimensional view.

We need more and better political conflict

Political conflict has a bad reputation. Many of us disdain it; we ask "why can't we all just get along?"

But here is the problem: without conflict, there is no politics. The things we agree on are not political. Politics is where we disagree. It's where we argue and fight.

In order for elections to be meaningful, parties have to disagree over competing policies and priorities. Without disagreement, there is no choice. Without choice, there is no meaningful democracy.

Conflict is what brings people into politics. If there are no stakes, why bother to participate?

But when conflict gets stuck too long on a single dimension, politics becomes zero-sum. The mentality becomes us versus them. It is under these conditions that political extremism and democratic backsliding are most likely to emerge.

If we are concerned about America's slide into authoritarianism, as we well should be, the response isn't asking Democrats to fight harder or 'moderate.' The answer is to stop accepting Republican conflicts and create new ones.

Yes, this means internal Democratic fights. Yes, this means uncertainty. But that's where democratic politics actually happens—in moments when new conflicts bring new people in. Until Democrats get this, they'll keep rehearsing those beautiful Bach fugues for a punk rock politics.

As I write in the conclusion of my Vox article:

Schattschneider called the people "semi-sovereign" because they can only choose between conflicting alternatives, developed by the major parties. The implication: Popular sovereignty depends on leaders willing to open up new conflicts and create new choices. As he understood: "The people are powerless if the political enterprise is not competitive. It is the competition of political organizations that provides the people with the opportunity to make a choice. Without this opportunity popular sovereignty amounts to nothing."

The people are waiting to be sovereign. They just need somebody to give them a fight worth joining.

Excellent Lee. Have already read it twice to get it to sink in.

I agree with most of this, but I don't agree Democrats should simply adopt the narrative that crime & immigration are "problems." Crime & immigration will always exist and always be a "problem." That's not the Republican political argument right now. Their argument as illustrated by the bully pulpit of the Trump administration is crime is out of control. Democrat cities are "war zones." Immigration is unchecked; basically an invasion.

There is much for Democratic Party operatives and politicians to work with to create political conflict without going anywhere near maintaining the status quo. Simply call out the over the top & ridiculous fear mongering is a good place to start. That's a large dose of common sense which the average voter, even low information voters not only agree with but also support.