One "Big Beautiful Bill" and the calculated confidence of unapologetic unpopularity

Or: How participation gaps, policy design, and status-driven voting let Republicans keep doing reverse Robin Hoods.

Republicans just contorted their coalition to pass regressive tax and spending legislation that polling shows Americans oppose 2-to-1. It is bad, incoherent policy that voters did not want. It is full of gimmicks. And yet. They still rushed to pass it.

Why?

Why did Republicans make this their signature achievement, despite the unpopularity and internal resistance? Will they actually pay any exceptional electoral penalty?

And most importantly: if Republicans don't pay any exceptional penalty for legislation that's both massively unpopular and internally divisive, what does that tell us about American politics

I don't think Republicans will pay any exceptional penalty for this legislation (beyond the usual midterm penalty for the party in the White House).

I think there are three main reasons, all of which tell us important things about our politics. Let’s dive in.

The Participation Gap: Who Votes vs. Who Gets Hurt

There will almost certainly be no lower-income voter backlash. Those most harmed by regressive policies participate least in electoral politics.

Roughly one in five Americans benefit from Medicaid. To qualify for Medicaid, your income needs to be pretty low—a little over the poverty level. And here in the United States, low-income voters participate at much lower rates than higher income voters. Much lower.

I made a chart, based on US Census data, to prove it. It’s pretty shocking.

What explains the income-turnout gap?

Well, as a general rule, across countries, the more unequal the society, the higher the gap.Mostly, this is because the more unequal the society, the more low-income voters think: what’s the point? It doesn’t matter whether I vote or not, nothing changes.

This creates a vicious cycle Republicans exploit.

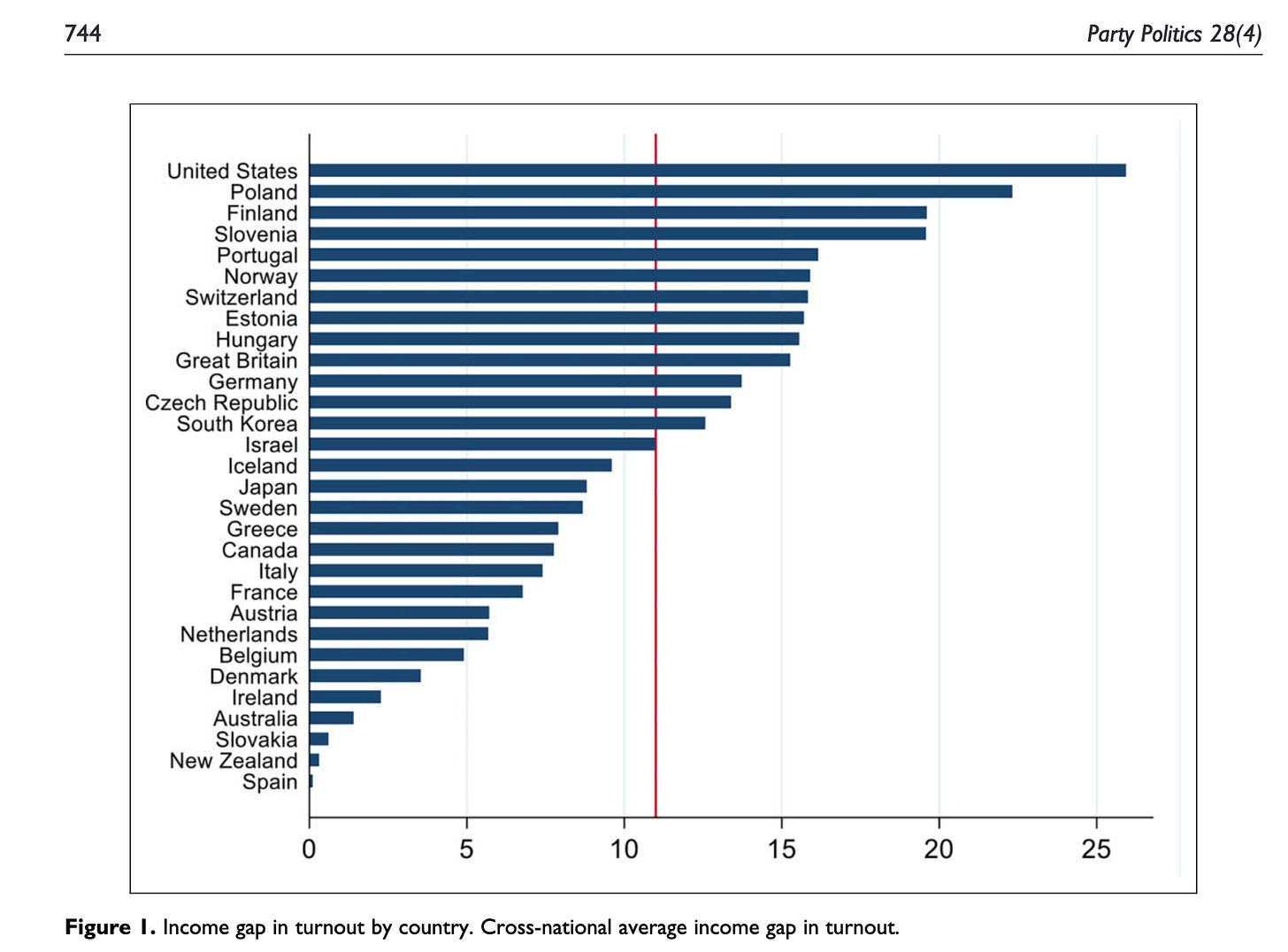

And the US is a real outlier here in the income-turnout gap. American Exceptionalism, indeed. The figure below comes from an informative paper by Matthew Polacko, “Inequality, policy polarization and the income gap in turnout”

However, this doesn't fully explain Republican confidence. Some middle-class voters do participate regularly and care deeply about these programs. The challenge is that even engaged voters face genuine difficulties tracing policy effects to political decisions.

The Magic of Policy Design: Timing and Traceability.

Republicans have done something clever with this bill: Frontload the popular stuff, delay the unpopular stuff. Tax benefits go into effect first. Social spending cuts go into effect later. In 2026, when voters file their taxes, they'll see the benefits. Trump and fellow Republicans will talk up these benefits. Most will go to the very rich, but if most taxpayers get something, they'll see the benefits in their own returns. People generally like paying lower taxes.

By contrast, the most unpopular parts—the cuts to Medicaid—won't go into effect until after the 2026 mid-terms. Until the cuts happen, it's harder to campaign against them.

Long timing also confuses "traceability." Apparently, Republicans have read R. Douglas Arnold's political science classic, The Logic of Congressional Action, which explains the importance of policy design: Make the benefits visible and obscure the costs. The less traceable the costs, the harder for the public to know who to blame. Who knows, by 2026, Republicans might be blaming Democrats for the cuts!

Even more: The connection between federal Medicaid cuts and recipients’ care isn't immediately obvious, especially since states often don't call their programs "Medicaid"—using names like SoonerCare in Oklahoma, Apple Health in Washington, or TennCare in Tennessee. Nearly all states use private insurance companies to run their Medicaid programs, meaning beneficiaries hold insurance cards from UnitedHealth or Blue Cross Blue Shield, further obscuring the federal program's role.

Confusing policy makes traceability hard.

Politics is more about status than materialism

Democrats are constantly talking about money and benefits and costs. But one of the funny things about us humans is that we don't actually care that much about how much money we have in the abstract. We care about how we're doing relative to others who we think are below us. We're deeply wired for status. What we care about is: are we doing better than the people we should be doing better than? We're much more motivated to avoid falling below others than we are to rise above them.

So we don't vote in our economic self-interest—we vote in our status interest. (Tali Mendelberg has a great essay on the centrality of status in politics, “Status, Symbols and Politics”)

The more we feel like we're in a zero-sum contest for resources, the less we care about absolute numbers, and the more we care about relative status. This is the conflict Republicans are driving. It's compelling because it's a story. It grabs our attention. It's far more compelling than wonky policy details.

As Vice President JD Vance wrote on X: "Everything else—the CBO score, the proper baseline, the minutiae of the Medicaid policy—is immaterial compared to the ICE money and immigration enforcement provisions."

And he’s probably right. This is the Republican playbook under Trump. It's one of the oldest political stories: the barbarians are at the gates, and unless we fight back, they will undermine everything good about our civilization. It plays on deep-seated fears about identity and status and freedom.

It may not be "rational" in the way highly educated liberals like me are taught to think about rationality. But it is a story in which "ordinary Americans" get to feel like heroes, preserving American greatness for future generations. It promises something greater than materialism. It promises a boost in status.

Democrats often call out this chicanery and try to get people to focus on details. But people don’t care about details, unless they fit into a larger story. But Democrats lack a competing narrative or defining conflict. They talk in abstract numbers about this many people who will be knocked into poverty, or have their Medicaid cut off. It’s all very clinical.

I think this explains why Republicans can confidently pass unpopular legislation. They understand that voters respond to status signals and moral categories more than policy outcomes. When the immigration narrative promises to restore proper hierarchies and defend cultural boundaries, it overwhelms concerns about healthcare cuts or tax inequity. The psychology of relative position trumps the math of absolute benefits.

One way Democrats could respond: make politics more explicitly about morality

But what if Democrats approached politics differently? What if they framed the conflict much more explicitly in moral terms. Moral appeals can be more powerful than economic appeals. Research shows moral appeals generate pride, hope, and enthusiasm that inspire political mobilization.

When people have given up on politics because "nothing changes," a story about fundamental dignity and respect might cut through fatalistic assumptions in ways that policy promises never could. .

Outrage at cruelty and indignity doesn't require understanding complex policy mechanics or waiting for delayed implementation. It's immediately comprehensible and emotionally compelling, potentially disrupting the careful attention management that Republicans depend on. When voters feel their fundamental values are under attack, policy complexity becomes irrelevant.

Fighting for "dignity and decency" reframes political conflict as "dignity vs. cruelty" and “decency vs. indecency.” If Democrats engage in a real moral fight here, they could link regressive economic policy to harsh treatment of immigrants to Trump’s grotesque White House corruption.

The hard part is to make it authentic, to channel outrage into a compelling story that disengaged voters can get excited about.

This goes against the main current in the Democratic Party — an overly intellectualized framework that treats politics as fundamentally rational, backed up by a consultant-polling complex that optimizes individual messages while missing the larger narrative. Individual policy messages don’t land if they don’t fit a larger narrative conflict.

The problem is that moral conviction can't be A/B tested. Moral conviction requires the kind of political risk-taking that threatens both consultant fees and carefully managed coalitions.

But I do think Democrats should lean into “Dignity and Decency” – it feels right to me.

Something fundamental about electoral democracy is operating differently than we thought. We should figure out what.

So yes, this monstrosity of a bill Republicans passed is widely unpopular. It's also bad policy. But if I had to guess, Republicans will not pay any exceptional electoral penalty for it. By October 2026, political attention will be elsewhere. Democrats may win back the House, but it won't be a wave. Republicans will probably hold the Senate.

So, to get back to my original question: if Republicans indeed do not pay any exceptional electoral penalty for a massively unpopular and regressive tax and spending bill, what does that tell us about American politics?

I think this tells us that individual policies and their popularity matter very little to how voters decide, and far less than we think they should. It may also tell us that tax and spending policy matter very little to how voters decide. It should also tell us that materialism matters much less than we think. And if so, it means we need to think about politics in different ways than we have been.

I think it means that we need to think about politics in terms of master narratives and dominant conflicts. And in terms of how our brains actually make sense of reality. And not the ways in which a generation of economists and economics-envying social scientists have tried to fit our brains into one-dimensional simplifications of ideology.

When a carnival barker salesman candidate can survive scandals, criminal indictments, policy unpopularity, and institutional opposition while mobilizing millions of voters, something fundamental about electoral democracy is operating differently than we thought. We should figure out what.

Lee, I think I have more contact with working class people than most academics and while your third point about Democrats neglecting to make an argument about morality may be accurate, I think you overlook the fact that the Republicans ARE making a moral argument. Democrats tend to ignore the question of deservingness. Especially among older working-class people there is a belief that government support should only go to those who deserve it: If you are an able-bodied person and not working, you don’t deserve benefits; ditto if you are in the country illegally. Thus, if Republicans claim that only such people will be kicked off Medicaid, that’s fine for many people. Closure of health clinics and rural hospitals would be a more effective counter-argument.

Although not relevant now, sometime in the future we’re going to have the same argument when it comes to reforming social security. People I know cite examples of others they know who are gaming social security disability—able-bodied people who can do as well getting disability as working low-paying jobs. When Republicans go after social security one of their defenses will be that they’re only going after lazy people who should be working.

Excellent, important piece. Discouraging, because extremely well argued. (I was glad you didn't try to morph it into something about the importance of creating additional Parties: this problem is largely--if not wholly--other, I think.) Anyhow, it's the best thing of yours that I have read to date. Thanks.