Are We Losing Our Democracy? Or Are We Losing Our Minds? Or Both?

Is America Really in Crisis, or Are Our Brains Just Wired to Think So? Yes.

How often does this happen to you? You meet up with a friend you haven’t seen for a while. The conversation goes something like this:

You: Great to see you. How are you?

Friend: Great to see you too, I’m doing well. No complaints. But the country…

You: Same. No complaints with me either. Feeling good. But the country…

Friend: I know! Can you believe… [Insert latest outrage, which then dominates conversation]

This happens to me a lot. Maybe I live a charmed life (I do).

But here are some polling numbers that surprised me. Most Americans also report that they are doing pretty well personally: 78 percent of Americans say they are satisfied with their personal life; 77 percent are satisfied with where they are living; 63 percent describe their financial situation as being "good”: 88 percent of Americans say they are happy overall.

And yet, the country… Roughly 80 percent say they are dissatisfied with the way things are going in the United States. And 64 percent believe U.S. democracy is "in crisis and at risk of failing.”

Is this weird?

The majority of Americans say they are actually doing surprisingly well. The economy really is strong (though not everyone is benefitting). And yet, the foundations of our democracy do feel like they are crumbling. One does not expect a relatively rich country where most people are doing pretty well to collapse into authoritarianism.

Now, I don’t want to get too rosy here. There is some real suffering that is happening in this country. US life expectancy is now declining for the first time, and out of line with the rest of the world (which has bounced back from a COVID dip). Drug overdose deaths have grown dramatically in the last several years. Almost 38 million Americans are living in poverty. (Although federal pandemic spending lifted millions of Americans out of poverty, at least temporarily.) Nor do I want to minimize the threats. Climate change poses a significant and uncertain threat. Wars in Ukraine and Gaza are creating tremendous uncertainty.

There are real threats, and real injustices. But if we are going to address and solve these and other problems collectively, we need to have some faith and trust in the government to steer and implement the large-scale solutions necessary.

And yet, it really does feel like we have worked ourselves into a state of counter-productive exaggerated panic and anger, such that we can no longer solve these problems anymore. And the failure to solve these problems contributes to more panic and anger. Which further undermines our collective problem-solving capacity. Which leads for calls to blow up the system entirely. Which…. well you get the idea: a kind of doom loop, if you will.

And this is where I really struggle. As somebody who studies democracy, I see real warning signs. I see an illiberal, authoritarian movement rising on the political right. And it’s important to call it out for what it is. But am I being overly alarmist in a way that contributes to a collective sense of learned helplessness?

I also see how the far-right authoritarian movement, led by Trump, is catalyzed by both some real and significant crises in declining parts of the country. I see how that has mixed with distrust into a rumbling rage that “the elites” have failed them, which makes the idea of “democracy” seem like a farce. But it is also true that many Trump supporters are doing quite well financially. So some of this outrage is... maybe exaggerated? (Please, don’t make me revisit the whole “economic anxiety” debate).

Going back to the late 1970s, most Americans have been satisfied with their lives. The percentages go up and down here and there. But overall, it’s a country of mostly satisfied people. For a decade and a half, half of the country even describes itself as “thriving.”

But the direction of the country? This bounces around much more. Lately it has been pretty low.

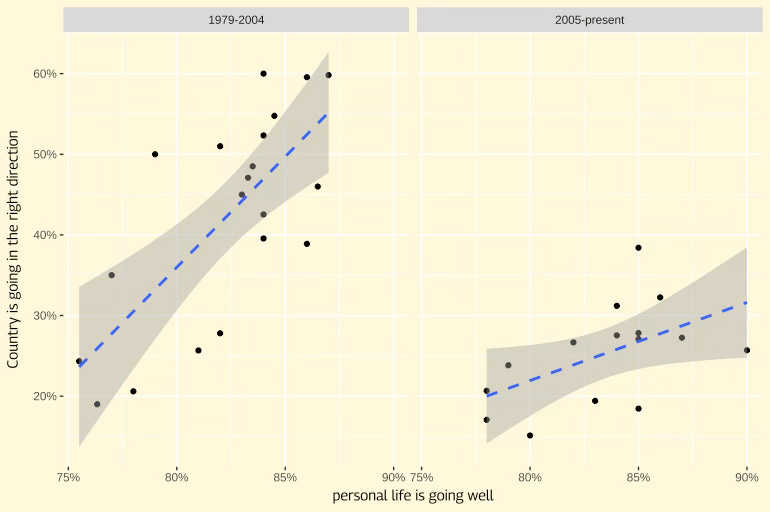

Is there a relationship between the two questions? Yes, but it’s complicated. You might expect that when more people are satisfied with their own lives, more people are also satisfied with the direction of the country. And you’d be right. But in the last two decades, the connection has attenuated considerably.

If you are a careful and devoted reader of this substack, you may recall a similar chart in my essay on how economic sentiment had become de-linked from presidential approval over the last two decades. I am now sensing a pattern. In this current era (the last two decades or so), our own fortunes are increasingly de-linked from our feelings towards the government and towards our leaders.

So why this disconnect? Something important has changed. But to understand what’s going on, we need to understand ourselves better.

This essay is an attempt to unravel these complicated interrelated forces. Fair warning: I may pose more questions than answers. But these are hard questions, and I’m starting to think through them.

The short version of my argument is this: The current political-media environment is toxic for our brains. We can’t manage this amount of constant conflict.

Our brains are wired to attend to and remember threats.

Our brains are incredibly complicated information processing networks. But broadly, I think it’s useful to think of our brains as essentially having two brains. I call them as Survival Brain and Enlightenment Brain.

This split corresponds to Daniel Kahneman’s “fast” and “slow” thinking. Fast thinking is survival brain. Slow thinking is enlightenment brain. This split also corresponds to “hot” vs “cold” cognition, or emotion vs logic. In reality, this dichotomy is not so simple. But as a shorthand, it helps us understand how and why we react in certain ways to certain stimuli and situations.

Generally, when we think about Thinking (capital T), we think Enlightenment Brain. We imagine ourselves critically examining everything, reading carefully and slowly, perhaps going on a long walk as we marinate on the right conclusion. This is the kind of critical thinking our educational system aims to cultivate. It’s what fills our ideals of democratic deliberation and the “public square.”

And yet we fall so far short of this most of the time. It’s a very high standard. It’s resource-demanding and exhausting. There’s only so much capital-T Thinking we can do — even those of us who have the luxury of time to do it. It’s much more efficient to default back onto our Survival Brain.

This is especially important in deciding what to pay attention to and what to store in long-term memory. Think about your past seven days. What are the most important news stories you’ve read? How much of what you’ve read has already been forgotten? How many of the headlines and social media posts did you just completely ignore?

Our brains are optimized for picking out the most important information from the world around us for consideration. And then, we further whittle that down to decide what to actually remember and integrate into our understanding of the world. As anybody who has ever studied for a test will remember, committing things to long-term memory is hard work. It requires real mental effort.

But certain things are easy to remember. If you were alive on 9/11, you probably remember that day in vivid detail. You probably remember the circumstances around the death of a loved one. You probably remember a painful break-up. If you were ever in a bad accident or a victim of a crime, you probably remember that quite clearly.

Our brains are wired to remember traumas. Presumably, this is a very good survival skill. Our brains are wired to pick up on threats and conflicts and dangers. This is so we can avoid them. This is a well-documented psychological phenomenon called “negativity bias.” Put simply, “bad is stronger then good.”

If you want to improve your memory, there are many tricks and techniques. All of these build around the automatic survival brain routines that immediately identify certain things as important, and worth attending to, and other things as not important, and not worth attending to. Our Enlightenment Brain can hack our Survival Brain. But it requires work and practice.

Very few of us think about how our minds actually work. We are taught that through sheer force of will, we can become better, more critical thinkers, and that more information is always better. But in an era of information overload, the bad crowds out the good more easily than ever. It’s a matter of absolute volumes, not percentages. There’s only so much we can pay attention to, and of that, only so much we can devote to encoding into long-term memory. Our processing capacity is the bottleneck.

Negativity bias helped us survive, but it’s poorly adapted for this current environment.

Our survival brains have some wisdom. It’s very good to be aware of threats and take them seriously. And when conflict starts, it’s very good to be aware of it. We depend on the press to hold power accountable. We depend on political opposition to hold power accountable.

But as with everything, balance is key. Too much negativity in media and politics is as bad as too little negativity.

Perhaps a useful metaphor is our immune system. An active and vigilant immune system is essential to our health. But an overactive immune system starts mis-identifying normal cell functioning as a threat. This causes all kinds of problems.

I’m not an immunologist, so I don’t want to take this too far, but I’ll just note that autoimmune diseases have been rising for 70 years, and leading researchers in the field think it has something to do with our changing environment. One theory is the so-called “hygiene hypothesis”, which suggests that with improved sanitation and urbanization, our cleaner and more indoor living environments gave our immune systems less to do, and so they started attacking healthy cells instead of foreign cells. Another hypothesis is that excessive stress and worry is over-activating our immune systems. A third is that harmful chemicals are triggering responses. But all of these are changes in the environment.

Our immune system, like our brain, is complicated. It gets triggered by different stimuli. But nobody is being urged to control their immune systems. We are, instead, trying to use our enlightenment brains to explain why autoimmune diseases are on the rise, and how we can improve our environments to limit them.

It’s possible our “negativity bias” operates similarly. It’s important to remain vigilant. But when we are constantly reading about threats and conflicts, we cannot disentangle our own circumstances. Indeed, studies show that, for certain people, news consumption becomes “problematic.” As one recent study describes it, for such people, all this news draws some people into a “constant state of high alert, kicking their surveillance motives into overdrive as the world becomes a dark and dangerous place…[A] vicious cycle can develop in which, rather than tuning out, they become drawn further in, obsessing over the news and checking for updates around the clock to alleviate their emotional distress.” For these people, severely problematic news consumption has real effects on their physical and mental health.

Like with autoimmune diseases, environmental triggers have changed. Our media and political environments have both changed considerably over the last several decades. And those changes are putting our negativity bias into overdrive.

The transformation of the news: From local and limited to national and non-stop

The big transformation over the last several decades is that news has gone from being mostly local and limited to being national and non-stop. We know all about the transformation from limited to non-stop because we experience it daily. Used to be that once you read the daily paper and watched the evening news, that was it. Now, we live in the era of the infinite scroll.

We also know about the collapse of local media, and the prodigious rate at which local newsrooms are shrinking or shuttering altogether. This has all kinds of bad consequences for democracy, because it undermines the ability to hold power accountable — a crucial role of the media. (We need some negative news, don’t you know!)

But it’s the interaction of these two trends that has had significant consequences for our information-processing brains.

When news was mostly local and limited, there was only so much bad news or crisis or threat that could fill one’s daily news consumption. Most local news was blah, and there was only so much space for it. Scan the front pages of local newspapers, and you’ll find a lot of human-interest boosterish stuff that will make you feel good about your community, and some banal stuff about local spending priorities, local businesses, and local sports.

But now there’s less and less of that. Local papers reach fewer and fewer homes. We have access to more news, and more national news, and that makes for a much more competitive news environment. It’s not just one or maybe two local newspapers that people subscribe to out of habit.

In a highly competitive online media environment, you need to grab people’s attention quickly. There is a whole art to writing headlines with more emotionally engaging words, and negative headlines get more clicks. Good news doesn’t really sell.

Again, this is not the fault of the media. It’s the fault of our brains. It’s just not news when things go as expected, because most things go as expected. Most planes land safely. That’s not news. But a plane crash, however rare it may be, is news. Journalists are people. Readers are people. People are more interested in bad than good. If doors are falling off planes, I want to know that.

In response to all the bad news, more people are cutting back on their news consumption. I guess this makes sense and is probably healthy. I have as well. But I worry, too, if the response is just to disengage. There needs to be balance.

The high cost of the high conflict of nationalized politics

So there’s more news, and more national news. That’s one change.

The second change is that national politics has become much nastier. So more focus on national news means more focus on high-conflict, high stakes, hyper-partisan conflict.

By every measure, partisan polarization has worsened considerably over the last three decades. The parties have separated geographically, informationally, culturally, and rhetorically. Republicans and Democrats operate almost completely separate epistemological worlds that share only one thing in common: the nation is in an existential struggle for its existence, and the threat to our country is coming from inside the borders.

In the 1990s, there was still quite a bit of overlap between Democrats and Republicans. Today that has collapsed into the high-stakes narrow conflict that you see in all the news. Of course, there are many analyses that suggest that in the mass public, maybe we are not as divided as this. But the news is mostly about conflict, and the biggest conflict entrepreneurs get the most attention. And with more time to fill on cable, and more clicks to generate on the internet, there is more space to focus on the crazies and the conflict entrepreneurs.

And the more we learn about all the threats, the more threatening they become. And the more they come to dominate our imagination. And the more they accumulate into a sense that the world is under threat.

A key source of threat news is coming from inside our political system — it’s our never-ending, very negative political campaigns. We experience a nonstop barrage of negative campaigning. These ads, um, add up. A 2007 meta-analysis on the effects of negative campaigning concluded that all that attacking “tends to reduce feelings of political efficacy, trust in government, and perhaps even satisfaction with government itself.”

That was 2007. Interestingly, the authors of that meta-analysis had conducted a previous meta-analysis in 1999, when they concluded that negative campaign advertising had no harmful political effects. In 2007, they wondered why their findings had changed. Maybe scholars had improved their methodologies. Or maybe the earlier findings were time-bound, from an era in which attack ads were rarer.

Even in 2009, when two of the authors revisited their 2007 warnings about the harmful effects of negative advertising in the Annual Review of Political Science, they noted that “few political campaigns are in fact overwhelmingly negative. We are more likely to hear about negative campaigns in the media, but relatively few ads are entirely negative, and most campaigns, on balance, are probably more positive than negative.”

And now, in 2024, here we are: we are living with the cumulative consequences of three decades of increasingly negative campaigning. Now, every elected national political leader has negative approval ratings. And, of course, we have two presidential candidates, both with high unfavorables.

In a two-candidate race, you just have to be the lesser of two evils. Or as Biden repeatedly puts it (in his folksy way): “don’t compare me to the almighty. Compare me to the alternative.” Understandably, if I’m running the Biden campaign, I know Biden’s approval ratings are probably stuck in the low 40s. So my theory of the case is simple: convince enough marginal voters that a second Trump presidency would be an absolute disaster. Scream from the mountains (aka, all the social media platforms) the sermons about how unhinged and dangerous Trump really is. In short: go negative.

And now, in campaign season, we’ve got a core of reporters ready to elevate the outrage. Confrontation and outrage and threat and uncertainty are all extremely engaging. Our brains are wired to pay attention to this stuff. So it will of course dominate.

So not surprisingly, 79 percent of Americans choose a negative word when asked to describe the state of US politics these days. And 65 percent of Americans are “exhausted” by politics and 55 percent are angry.

Things have clearly gotten more conflictual. It is not just you. The tone of US political speech has turned quantifiably more negative since early 2016, when Trump became the Republican frontrunner. He brought other politicians down to his level. But Trump’s success also depended on a politics of high conflict and low trust in the first place.

So here’s where I think we are: Our brains evolved to handle a world with some crisis and some conflict. Our brains are not equipped to handle an information environment like today — with constant crisis and conflict, especially political conflict that activates so many of our self-identities. When we watch the news, we get transported and drawn in. And it alters our sense of reality. This is a huge problem. It is undermining our ability to govern ourselves collectively.

Or, in billboard slogan version: Welcome to "Permo-Alarm-Politix"

How do we manage negativity and conflict? We actually need some of it for a healthy politics.

So what do we do about all this?

A typical essay in this style would offer these usual cliched responses: The press should report more good news. Campaigns should be less negative. Voters should stop rewarding negative campaigns. Citizens should stop clicking on negative headlines. We should share a meal with someone we disagree with, and understand the world through their eyes. We should all just calm the frick down.

Sound familiar?

This is where I get super-frustrated.

Because one, it’s not realistic, given all of the structural dynamics in our politics and media, and the way in which our brains work in the first place.

And two, some negativity is valuable.

We might bemoan that lack of trust in our politics, but we also want a government that deserves our trust. And the best way to achieve that is through an independent and adversarial press, and a political system of checks and balances. We need a watchdog media and political opposition. We need dissent and conflict. Otherwise, we become a totalitarian state. In Russia, for example, there is no political opposition, and no real independent media.

Media reform is not normally my focus, but I’m pretty convinced that foundation or university-supported not-for-profit models are best equipped for the current era. With only a few exceptions, for-profit journalism can only survive if it delivers high-alarm, low-information, mass-appeal content that’s cheap to produce but attracts lots of eyeballs. That’s not great. And it’s terrible for local journalism, and costly investigative reporting.

Of course, my big theme and focus is on the electoral and party system that generates all this excessive conflict, so I’ll do my usual spiel. If we had an electoral system that allowed for modest multipartyism, we’d have less binary conflict. Countries with more proportional, multiparty systems have less binary conflict, and more shifting coalitions. They have less negative campaigning. Yes, there are some global challenges to democracy. But some countries are weathering that better than others.

It’s okay for people to be dissatisfied. Some people should be dissatisfied. Some negativity and criticism is essential for a healthy democracy. But there’s a balance. If there’s a real crisis and failure of government, we should be mad. But we don’t need to invent crises that don’t exist, or pretend our country is run by a crime family when it’s not.

My worry is that by over-stating the crisis, we undermine the ability of government to work — which of course, leads to more people who want to dismantle the idea of government altogether.

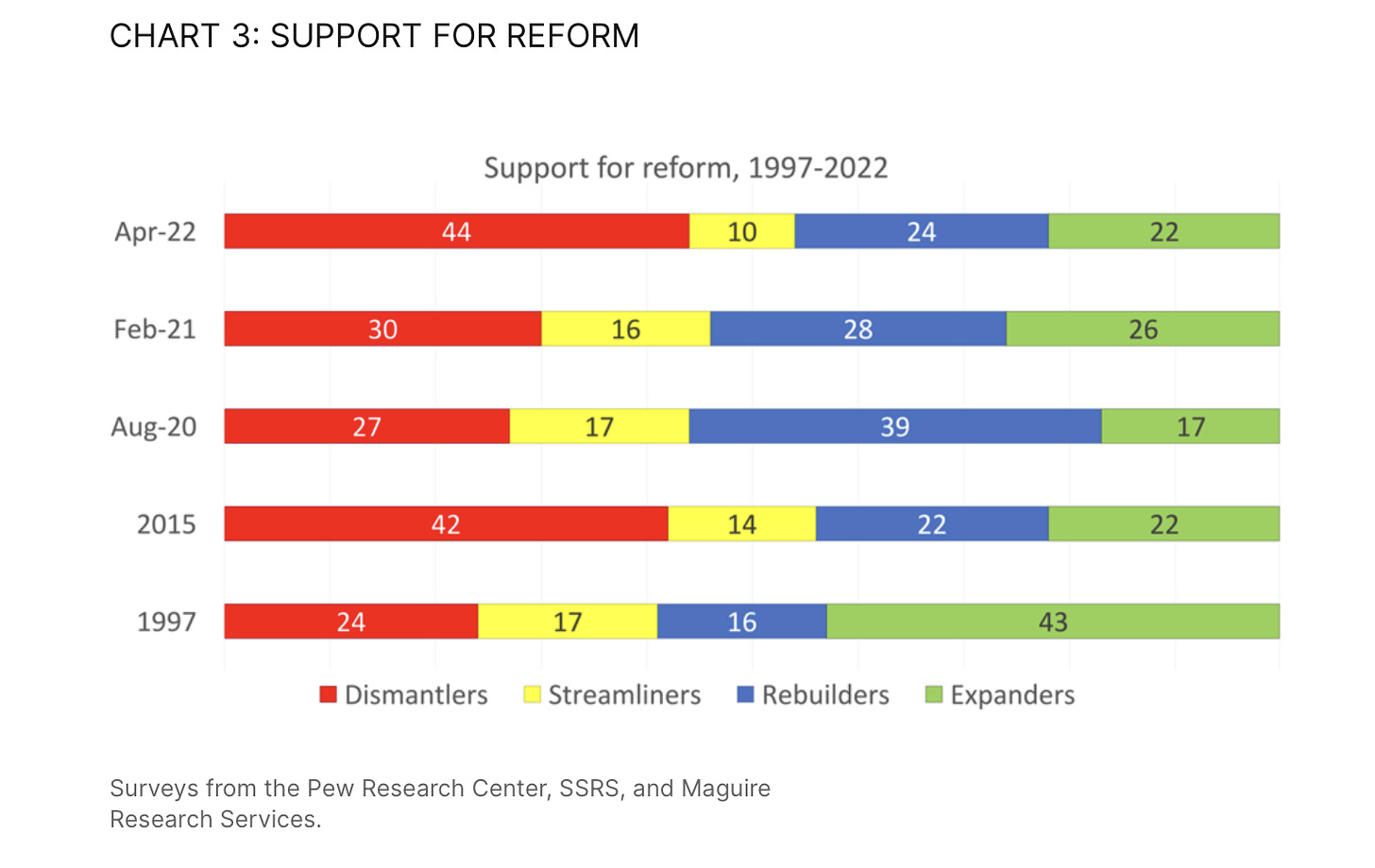

Here I’ll draw on a few charts from a recent Brookings report from Paul Light, who has been tracking public demand for government reform.

First, support for major change is very high. It has been high for a decade.

Over recent years, support for rebuilding vs dismantling has bounced back and forth. I consider myself a rebuilder. But to make the case for rebuilding is to make the case that the government can work well. That requires a certain degree of trust.

When trust declines, support for ambitious government policy also declines, which makes it harder for the government to actually solve the problems. Lower levels of institutional trust contribute to more support for challengers and third party candidates. As I explained in a previous post, RFK Jr’s traction is easily explainable by the overall levels of system distrust. Kennedy is decidedly a dismantler. So is Trump. Both thrive in a low-trust politics of constant threat. Trump is a chaos candidate not just because he creates chaos, but because chaos boosts his appeal.

Again: we have real problems. Some of their criticisms of the system have some justification. But we also have fake problems. And we are losing the ability to tell the difference between them as we are overwhelmed with constant alarm.

So here I’ll leave you with a final thought, one that makes me uncomfortable because I’m not sure what to do with it:

Maybe it’s because so many of us have it so relatively good that we can spend so much of our time paying attention to threats. And maybe it’s precisely because we have so much to lose that we are so vigilant. If that’s the case, does democracy need more genuine external stress to actually survive?

Huh.

I read somewhere that the cure for democracy is more democracy (more multiparty-ism, more proportional representation) and that dealing with whatever the risks associated with more freedom is far better than dealing with the risks associated with less freedom. I think the answer to your last sentence is yes.