Why You Might Be a Democracy Hypocrite (And Why I Might Be Too)

Blame it on the high-stakes partisan polarization that is putting our democracy on spongy ground.

Hello, my name is Lee, I’m a political scientist, and I might be a democracy hypocrite.

And you might be too.

And if so, it’s totally understandable, and perhaps even rational: The stakes are high, and we don’t have two parties equally committed to democracy.

So maybe if democracy is really at stake, extraordinary actions really are necessary. I’m not even sure what I mean by “extraordinary actions.” And just saying that makes my head spin, because I know it can’t be right.

But what else do you do when one side stops playing by the normal rules?

I’ve been thinking about these questions a lot in light of where we are in American politics these days. I’ve also been thinking about it in the context of a major new report I co-authored with Joe Goldman and Oscar Pocasangre: Democracy Hypocrisy: Examining America’s Fragile Democratic Convictions

The report analyzes lots of survey data. I’ll cover some of the key findings in this piece, and riff a bit on the consequences. But let’s start out with a quick diagnostic…

Take this quiz and find out: Are you in the elite 8 percent of consistent democracy supporters?

I’m not going to go through the entire survey here to diagnose you. Instead, I’ll just ask you five questions:

First off, and I hope this is an easy one: Would you say that having a democratic system is a good form of government?

I’m hoping you said yes. (If not, please see me after class)

But now we get into more complicated territory:

Please read the following scenarios and consider: How appropriate would it be for President Biden to take action on his own, even if the Constitution does not give him the explicit power to act without congressional approval.

- The country is facing an immediate military threat

- A large majority of the American people believe that the president should act

- The president knows it is the right thing to do for the American people

- The president has sought a compromise with Congress but the other party is playing partisan games

Think about these scenarios. Conjure up, if you like, an issue you care a lot about, and imagine Republican congressional intransigence. That’s what I’m doing as I write. And I’m … struggling here. If it’s a significant act on climate or gun safety — or another issue I really care about. Then … maybe? I mean, these are some urgent life and death issues, right? And I can’t trust Republicans to do the right thing, can I? And a Democrat might only be in the White House for a limited time. And the Constitution is silent on lots of things, and so maybe… and Oh Sugarplum Fudge! I might really be a democracy hypocrite!

I’m a political scientist. I know that democracy is a fragile agreement that relies on restraint. So I know what the “correct” answers are supposed to be. I know that extra-constitutional executive aggrandizement and overreach are key drivers of democratic breakdown. I know that these are the typical excuses would-be autocrats give for over-stepping constitutional lines. And I know that if “President Biden” were swapped out for “President Trump” I would feel completely differently.

I just co-wrote this whole report about democracy hypocrisy. And yet, here I am, admitting for all the world that when the stakes are high, commitment to democratic norms is… hard. Very, very hard.

I’m not alone.

Only about 1 in 4 of Americans consistently and uniformly support democratic norms.

Support drops to 1 in 12 when we consider specific scenarios of unilateral executive action.

In short: Our democracy is on spongy ground

And with that … it’s time to dig into the findings of our report.

Support for democracy is more superficial than it should be

A quick plug on why this report is significant: It’s based on panel data over seven years and four surveys. We asked the same people the same questions over multiple years. Panel data like this is very rare.

This means we can observe real people, changing their minds, in real time, depending on who’s in the White House. In other words: Hypocrisy in action.

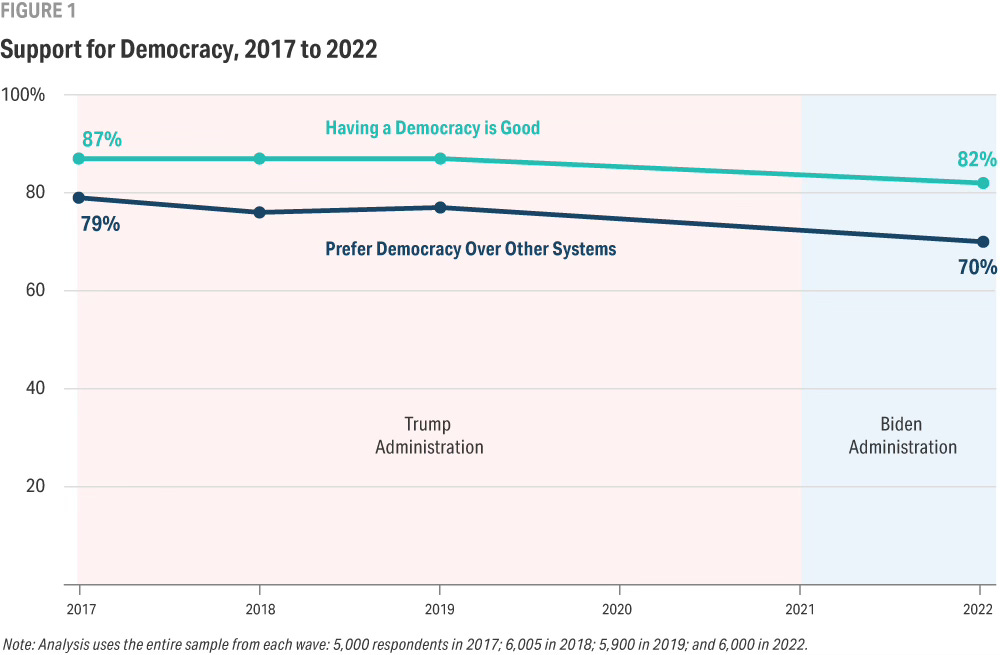

Let’s start at the beginning: Do we think having a democracy is good? Mostly, we do. Do we prefer democracy over other systems? Mostly we do.

Yes, there are some worrying trends here. Support for democracy is down. But it’s still in super-majority territory, which is good.

But now, let’s test out how support for particular principles of liberal democracy, like congressional oversight and a free press, stack up.

Here, the ground starts to feel spongier.

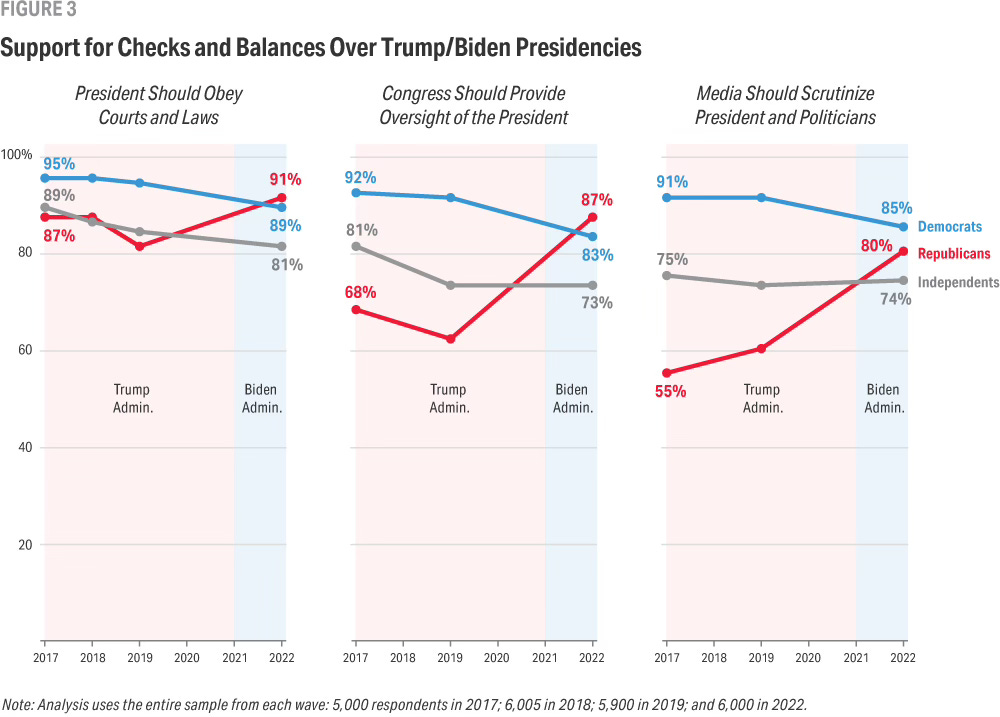

Overall, we’ve got high support for these principles.

But many Republicans in particular are fair-weather supporters of congressional oversight and a free press. They like these checks and balances and oversight when Biden is in the White House. When Trump’s in the White House? Eh… Not so much.

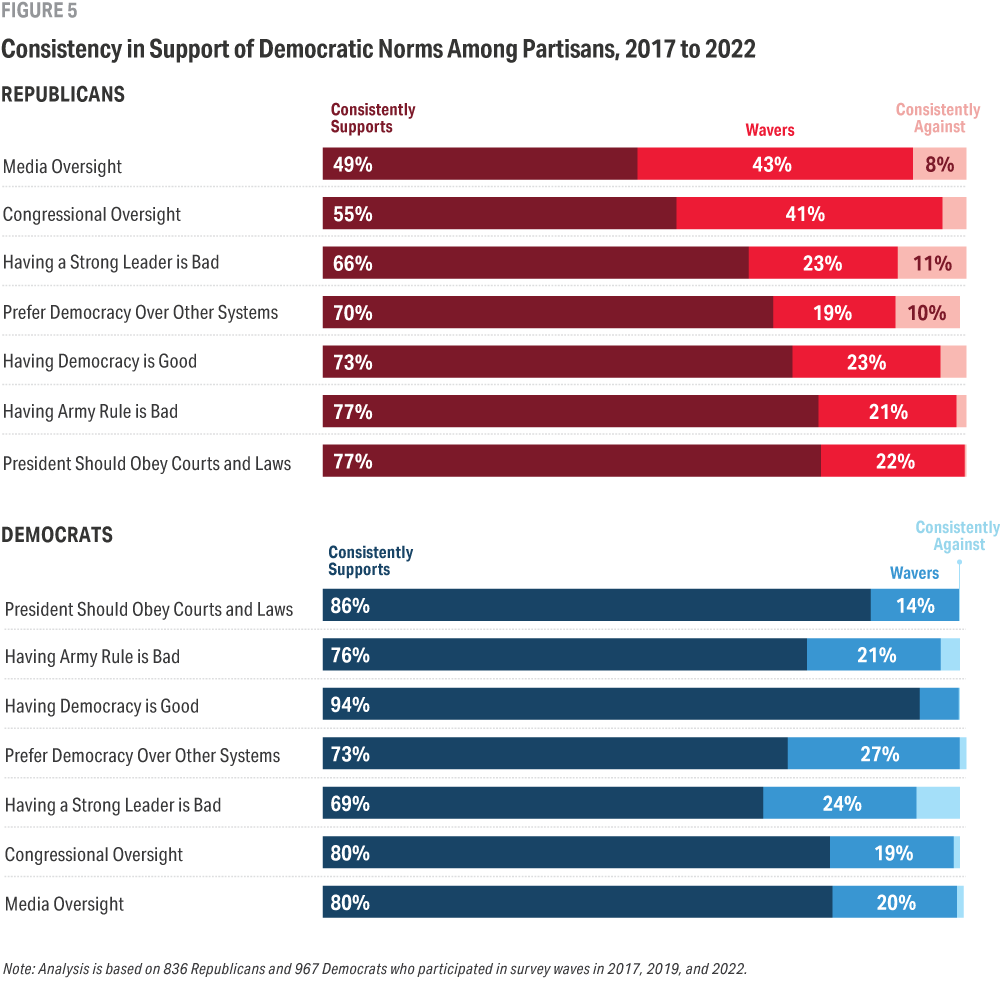

The powerful thing about panel data is that we don’t just have to rely on aggregates. We can observe how individuals waver across surveys. And they waver quite a bit. On average, for each issue on its own, the share of respondents who wavered across multiple surveys is about one in four.

This is … not great. But wait. It gets more discouraging. When we get into the specific scenarios, the inconsistencies multiply. Is it okay for the president to take action on his own, even when the Constitution does not give him explicit power?

Well, to most people, that depends: Is it President Trump, or President Biden? If it’s my guy, it’s okay. If it’s the other guy…. no way in hell!

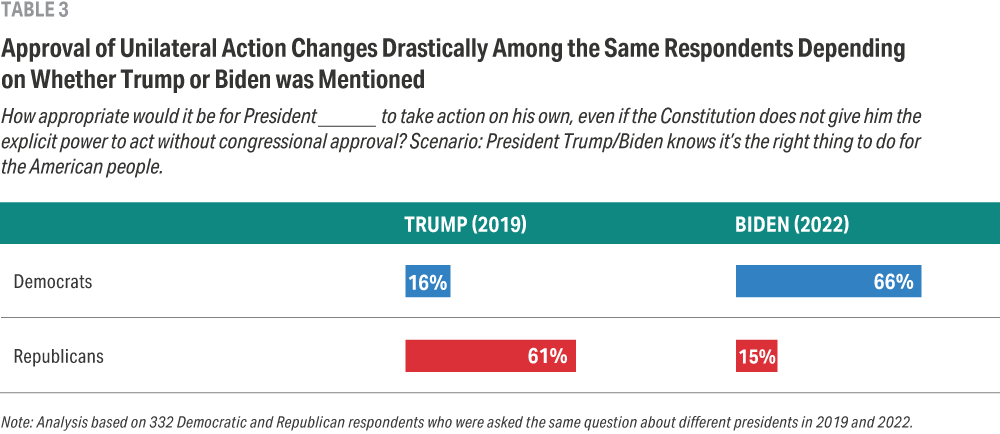

In 2019, with Trump in the White House, a majority of Republicans said it’s okay for President Trump to act on his own, even if the Constitution does not give him explicit power. Democrats naturally disagreed.

But when it was 2022 and the president was Joe Biden, the numbers completely reversed. These are truly remarkable swings.

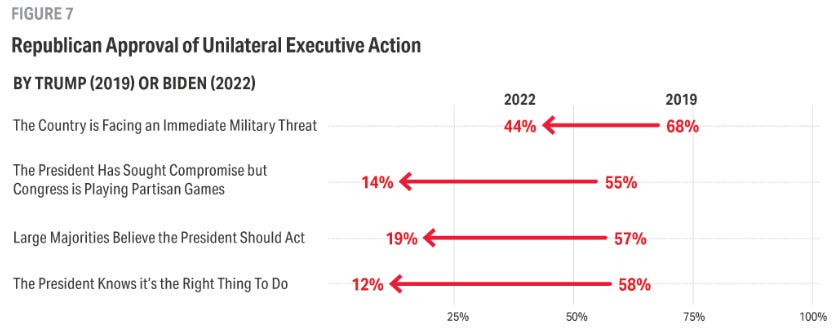

Here’s how Republicans shift across questions:

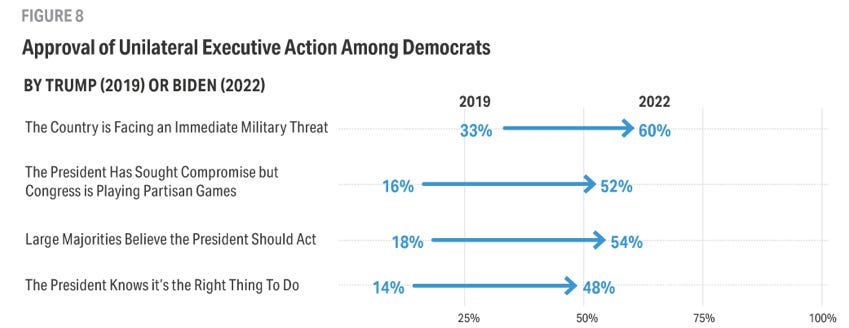

And Democrats…

When we add it all together, across all the surveys and many questions, that’s where we get the big finding about democratic hypocrisy

Only about 27 percent of Americans consistently and uniformly support democratic norms in a battery of questions across multiple survey waves, including 45% of Democrats, 13% of Republicans, and 18% of Independents. When adding responses to hypothetical scenarios about unilateral action by the president, the share of Americans that consistently supports democratic norms over this time period drops to just 8 percent, including 10% of Democrats, 5% of Republicans, and 11% of Independents.

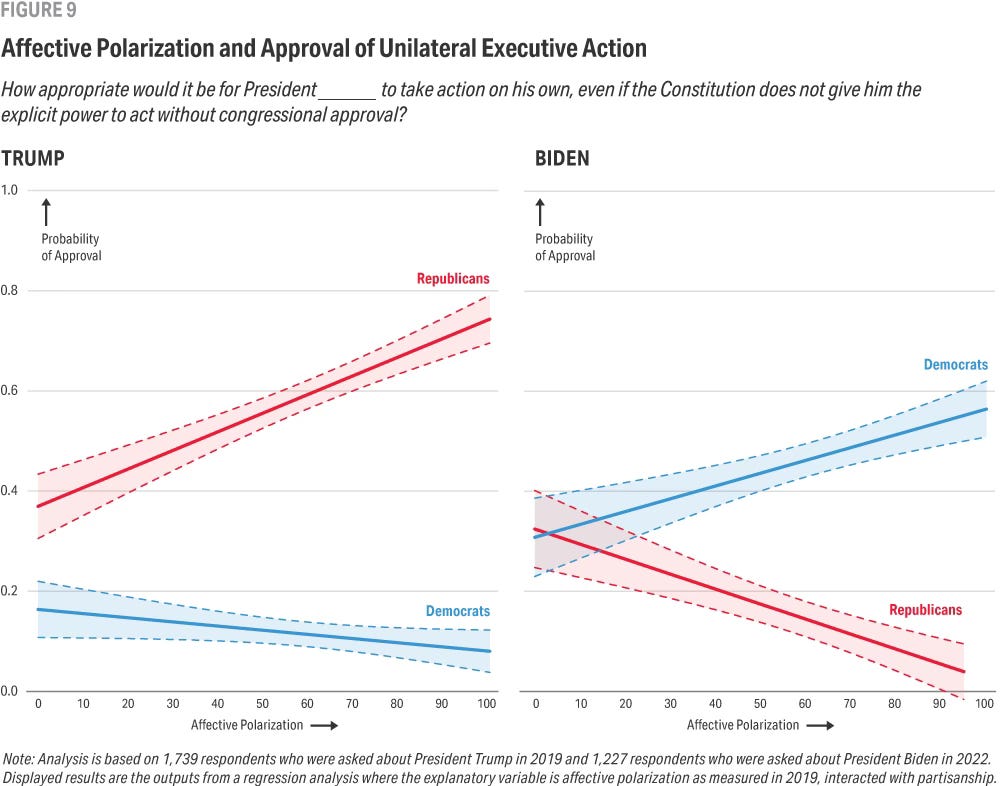

So why are so many people so inconsistent? A key factor is “Affective Polarization” (the somewhat clunky political science term that describes how much people dislike the opposite party compared to their own party).

Basically, if you are a Republican who sees a huge difference between Republicans and Democrats, you are much more willing to tolerate executive aggrandizement by Trump, and much more likely to oppose Biden’s aggrandizement. And if you are a Democrat, it’s the other way around.

Okay, so extreme partisanship is a key part of the problem here. But what about Independents? Can they save us?

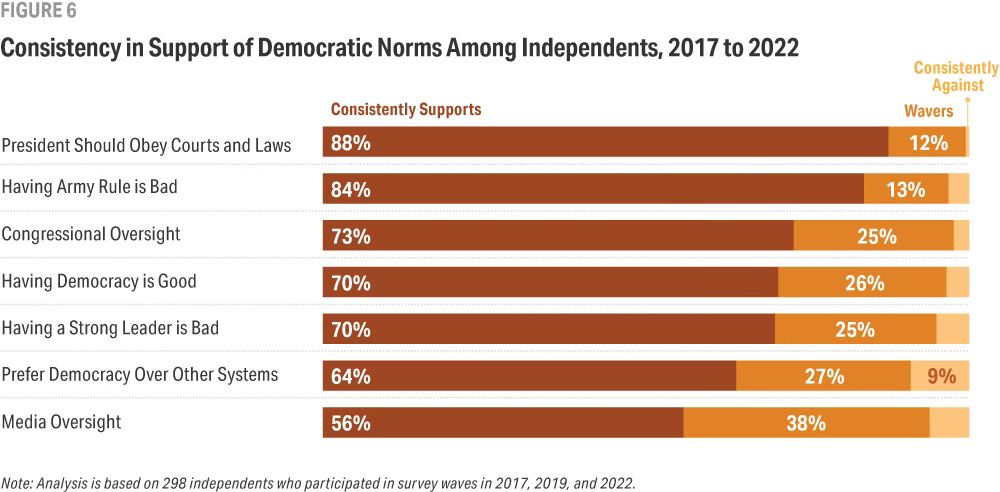

Unfortunately, the evidence here is not super-encouraging. As we note in the report, self-declared Independents are also inconsistent in their support for democratic norms, though their inconsistency across waves appears random (not tied to partisan support).

Other work suggests that Independents are more prone to anti-system views. Overall, our report finds them a little less supportive of democracy than partisans.

If you want some good news, well, there’s at least one piece in our report: We find few “consistent authoritarians” — which we define as Americans who consistently justify political violence or support alternatives to democracy over multiple survey waves. We estimate only 8% of the public meets this dismal stability.

A growing pile of scholarship agrees: democracy hypocrisy is real, it’s dangerous, and it’s linked to high-stakes partisan polarization.

Our report is unique because we have panel data. Our conclusions are consistent with what other scholars are finding: Most people support democracy in the abstract. But in the specifics, support gets squishier. And the more one probes with specific scenarios, the squishier it gets.

Study after study finds that when partisanship and democracy tussle, partisanship usually wins, especially in high-stakes polarized politics. Put simply, most people put partisanship ahead of democratic commitments.

People easily make excuses for their side’s rule-bending as necessary given the circumstances, or that it’s just NBD (no big deal). Everyone does it. Excuses come especially easily when elites on their side say it’s fine.

These same people, however, are particularly attuned to the other side’s every action as potentially un-democratic. Even ordinary political activity becomes a threat.

Generally, the partisan willingness to violate democratic norms is the highest among people who view opposing partisans as most threatening. This is hardly surprising — if you think the opposing party winning represents an existential threat to democracy and/or your fundamental moral values and well-being, then perhaps it’s appropriate (and maybe just this once) to change the rules to save democracy.

A few scholars have recently labeled this problem the “subversion dilemma” — a term that nicely captures the core devil’s logic here: If I, as a Democrat, say that Democrats should take extraordinary political hardball actions to expand voting rights, because democracy is facing an existential threat, am I just fueling Republican misperceptions that Democrats want to rig elections to win them, which in turn justifies Republican hardball to restrict voting rights? As the authors of the subversion dilemma paper warn: “the belief that the other side will subvert democracy leads partisans to support subverting it themselves.”

Whether these beliefs are based on misperceptions is sometimes hard to tell. Maybe I’m a victim of a biased media?

And I do know that in high-stakes environments of deep binary partisan polarization, it becomes much easier to demonize the threat of the other side. Thus, high levels of affective polarization correlate with high willingness to put partisanship ahead of democracy, both at an individual and a societal level. Yet, as an individual, I still think I’m being consistent with my deeply-grounded views about democratic equality.

Yet, once the dangerous doom loop of misperception and demonization gets going, democratic trust gives way to a “strike first” mentality. To quote one recent study:, “Given the self-reinforcing nature of enemy perceptions, democratic grievances are likely to pile up. Claims and counterclaims of democratic rule violations tend to harden into narratives in which both sides describe each other as existential threats to democracy.”

Which is pretty much where we are, here in 2024…

So, what happens when one party turns against democracy in a two-party system? Nothing good

The looming orange elephant in the room, of course, is that the Republican frontrunner is running as the first openly authoritarian presidential candidate in American history. He talks freely about vengeance and dictatorship. He says he will “root out the communists, Marxists, fascists, and the radical left thugs that live like vermin within the confines of our country that lie and steal and cheat on elections.” This is not normal democracy talk.

Usually, however, would-be authoritarians are more coy about their intentions, framing even authoritarian acts as somehow democratic. Trump is not. Most would-be authoritarians around the world are coy because they reasonably expect that voters will punish such talk. After all, most citizens in most countries think democracy is a pretty good system, and don’t want to give it up.

But Trump has tested the limits of what voters will tolerate, time and time and time again. Each time, he has learned he can get away with quite a bit. Partisanship is more powerful than any abstract commitment to democracy. And besides, he’s already convinced many Republicans that Democrats are the true threat to democracy, because they’re the ones who rig elections. So it’s all justified, right?

Over the past three years, Republican voters have become more likely to think January 6 was a minor incident, worthy of forgetting. Trump remains ascendant. And as any parenting book will tell you, rewarding bratty behavior over and over only turns your children into bigger brats.

But here’s where the cognitive psychology of high-stakes binary polarization becomes so destructive. If one were to remain a Republican after all Trump has said and done, one would need to shape one’s understanding of reality to justify that decision. And many have.

Understandably, there was no real choice here. For most Republicans , the alternative of becoming a Democrat was just… not possible, given their conception of what being a Democrat meant: Democrats were the opposition.

And in a two-party system, there are only… two alternatives — support the other party, or become politically homeless. So, many Republicans updated their understanding of events to fit with their identity: being a Republican.

People are group creatures, and they want to belong. To most people, belonging is more important than truth. Social isolation is real, objective, and terrible. Truth can feel more malleable and subjective.

Trump’s conflict-seeking approach is a tried-and-true tactic of authoritarian leadership. By escalating conflicts, Trump hardened the boundaries of us and them. He is constantly forcing people to choose sides. The more the gap widens, the more he can consolidate power.

Because what are Republicans going to do? Vote for the Democrat? That’s asking a lot, if Democrats have been the opposition party for your entire political life.

Vote for a third party candidate? Go ahead, throw your vote away.

Why electoral reform is the best path out of democracy hypocrisy

And here, once again, is why I see electoral reform as so essential.

Imagine if fusion voting were widely legal in the upcoming presidential election. Imagine a third party, say, the “Constitutional Republicans.” Such a party could offer its ballot line to pro-democracy Democrat like Joe Biden. They could send a message: “We’re not Democrats, but for this election, we’re supporting Joe Biden because principles of constitutional democracy are at stake.”

Such a party (or really multiple new parties) could offer new political identities and homes to those who feel trapped and isolated in the current two-party doom loop. By making politics less binary, more parties could sap Trump of his not-so-secret conflict-exploding power the binary two-party system gives him. There is no lesser of three evils.

A “Constitutional Republican” party would hold the balance of power in key swing states by organizing a crucial voting bloc. By organizing this voting bloc, this party could demonstrate its power and even bargain for commitments and cabinet posts in a potential second Biden administration. This would empower and engage the voters who must need to be engaged and empowered to protect our democracy right now – those who really do think of themselves as Constitutional Republicans.

Here, the story of Poland’s 2023 election, held under multi party proportional representation, offers some useful guidance in responding to an authoritarianism. Three opposition parties ran as a loose coalition, and won a majority of seats.

As Anne Applebaum (an expert in Polish politics) observed, “The existence of three opposition parties meant that different messages were heard by different parts of the electorate, on the center-right as well as the center-left. Some of the candidates attacked PiS. Some used the language of unity and called for an end to polarization.” The parties have since formed a governing coalition that promises “to restore rule of law, address the climate crisis, and improve Poland’s track record on women’s rights.”

Back here at home, the stakes are growing ever higher, and the authoritarian rhetoric ever higher. One would hope we’d see some genuine pushback here. But… if many of us really are democracy hypocrites, maybe this is not a realistic hope.

And that is a depressing thought.

Ultimately, democracy depends on both leaders and structures. We need leaders who hold firm to the commitments of restraint and core democratic norms, even when citizens may be willing to tolerate deviance. But we also need structures that enable citizens to punish such deviances without having to sacrifice other things that they hold dear.

Here’s the bottom line: We should never face a choice between upholding democracy and preserving our core values. Because when we’re put in that position, we, the citizens, might make the democracy-weakening choice. And if our leaders know what they can get away with, they might just make the wrong choices for us.

When reaching for a simple definition of democracy, I often reach for Adam Przeworski’s definition: “a system in which parties lose elections” But then I ask myself: will we still have a democracy if Republicans win in 2024? And if the answer is no, then I ask myself: if democracy depends on Democrats winning in November, do we have a democracy at all?

Spongy ground, indeed.

Thanks for this. Am new to both Substack and Medium.

Your 2021 New America study on Primaries has been ever-present in my thinking since I saw it in mid-2022.

I have been thinking hard about how to break polarization since early in the 2020 nomination contest. And even further back, in late 2015, when I could not get members of my Democratic-leaning discussion group to stop sneering and ask themselves “Why are lots of people supporting Trump?” And feeling their complacent stares when I told them to get out and help me and others work to prevent a 2016 Trump win against a weak insider-favored candidate (essentially coronated like 2024 appears to be).

Clearly, preventing a 2nd Trump presidency is vital. As this essay makes so clear, merely fending off Trump is insufficient if much of the public is ready to toss out the rules depending on who won.

Polarization has causes. I argue that its chief cause was the response of the parties when faced with the need to fund candidate recommendation processes (nominations) using primaries instead of conventions. Their response in the 1990s was to swivel their focus away from voters and towards campaign finance donors. It led to Gingrich’s culture wars. Recent studies show that conservatives tend to be very sensitive to cultural differences; hence responsive to funding appeals based on perceived “threats” stemming from such differences. The Democrats, responded by moving rightward. Cash welfare was gutted; the poor vote but do not donate. Hollowing out our low/semi-skilled industrial workforce (caused mostly because of automation instead of globalization) found no mass of small donors to push back. Donor money flowed to pave the way to the 2008 Great Recession, arbitrary-looking bailouts and tender treatment of the crooks. Donors found little to object to tax-policies that drive wealth concentration. All of this devastated support for the Democrats in rural areas.

Trump was symptom, not cause. Yet many still point at Trump instead of the true culprit, a primary system that was an easy target for abuse by the big donors and the elites of both parties.

You refer to Fusion voting as a help. In other contexts, you also refer to a more effective remedy, Top 5 Ranked Choice Voting. (Note: I have found no reference to a proposal to a method that combines both concepts, but, off hand, it seems doable.) Worthy targets, certainly. But, in the context of hundreds of state and local systems, not easily within the power of a new administration, no matter how progressive. Certainly, these remedies would help. But they have proven hard to sell against the waves of pushback from donor groups quite happy with the status quo.

No, there needs to be a practical, achievable path that the 2024 Democrats can base their campaign on.

You touched on vouchers in a 2016 VOX piece. But I can find no words from you since (unless they were in a podcast).

There is a path forward that is relatively inexpensive, well within the normal legislative power of a unified government (as Biden had for 2 years; perhaps too narrow a mandate to make it happen, but squeezing another $10 billion into the Inflation Reduction Act doesn’t sound like it would have been too hard), and immune to reversal by a radical Supreme Court (they’ve already ruled on it in the case of Seattle). And, most important, sellable to the public.

But here is the hard part. It will be sellable only if Biden (or some candidate) comes out and confesses the truth. The truth about how he and both parties have contributed to our dismal state because, since 1992, they could not figure out any other way to get the steadily increasing campaign finance money they needed. I’m currently working on a draft speech Biden should make.

I just posted a short summary about the path to Campaign Finance Vouchers on Substack: https://michaelfoxworth.substack.com/p/achilles-heel-of-control-by-big-campaign I plan to publish more, but until then, there is an embedded link to a YouTube video that leads to more detail.

The big special interest donors are nervous about Trump and hoping for Halley. But regardless, they are unambiguously opposed to vouchers – they recognize them to be an existential threat to their current dominance of policy.

In 2020, Gillibrand and Sanders both added vouchers to their platforms but didn’t push them enough to get anyone’s attention. After 2020, party elites and donors asked to go hard at climate change. Ok, needed. I’m as terrified as anyone else. BUT they ignored making the tiny investment in vouchers that would have paved the way toward a government that could set us on a secure path to fixing the problem.

Before the passage of the 25th Amendment, it was unclear if the Vice President actually became the president or just took over the responsibilities. Arguably, the latter interpretation is more true to the text. Yet when William Henry Harrison died in office, John Tyler took the oath of office and became President, a precedent that was followed by several other Vice Presidents. If Tyler's actions were unconstitutional, I argue that they were still correct and democratic, a "bug" in the Constitution that had to be addressed in the moment. In the absence of a clear Constitutional directive, Tyler did what he thought was right, and his actions were justified post-hoc through the amendment process.

I feel roughly the same way about your question on an urgent military threat, and in this case the argument is much clearer. The President is the Commander-in-Chief and takes an oath to protect the nation from threats. If the threat were urgent, failure to act would be a failure of the oath of office. I have trouble foreseeing why responding to the threat would be unconstitutional given the President's broad powers here (even habeus corpus doesn't apply in time of "war or public danger," which Lincoln exploited to arrest political enemies during the civil war). But if such a scenario presented itself, I feel that any such prohibitions are likely to be further "bugs" in the Constitution from which the higher mandate of self-preservation of the republic takes precedent.

I suspect in most reasonable scenarios people think of for this question, it would be an action that they would support amending the constitution to permit post-hoc. A possible version of such an amendment would be an emergency powers amendment. Many modern democracies have laws or constitutional provisions for emergency powers precisely because military conflict often requires setting aside some of the regular rules of governance. Granted, abuse of such provisions is how most authoritarians seize power, but this is one of those difficult facts that makes democracies hard to do right.

Does this attitude make me support undemocratic norms? I don't know. There are certainly lines I still wouldn't cross. I would not, for example, support a violation of the War Powers Act even if the President considered the threat existential. Nor would I consider it permissible to continue the course of action after an explicit prohibition by a court order. But overall I would still describe myself as staunchly pro-democracy even with the belief that the president should probably seize power in some of these scenarios. Yet by the question you asked I would not be. I'm not convinced the survey is drawing the right conclusion for this question specifically.