What the Apportionment Act of 1842 tells us about today's gerrymandering wars

And why reform might be closer than you think

Texas has now fired the first shots in the great gerrymandering wars of the mid-2020s. This is only getting started, I fear. Once war starts, it’s hard to control.

Mid-decade redistricting was once rare. I predict states will now draw their lines every two years (at least for as long as we continue to use single-member districts).

It will get even more aggressive when the Supreme Court completely guts Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act during its next term (as most expect it to do). The effect will be a green light for racial gerrymandering, which will open up many more possibilities for Republican gerrymanders, especially in the South.

How much worse can this get? Where does it end?

I’m a student of history. And what’s happening now reminds me of the gerrymandering wars of the 1830s, which ultimately led to the single-member district mandate in the Apportionment Act of 1842 – a major electoral reform that helps us understand why we have the rules we have today. (No, the Constitution does not mandate single-member districts; No, the Framers most definitely did not envision it, or the two-party system for that matter).

I wrote about the 1842 Act in my book, Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America. It was one of several brief cases in the book’s penultimate chapter, which explores how and why major electoral reforms do sometimes happen, despite the odds.

So, to those skeptics and haters out there who say proportional representation could never happen, I say: read your history. Major change is more common than you might think.

But before I share the full passage from my book, I’ll just give you the capsule summary to make the most important points clear.

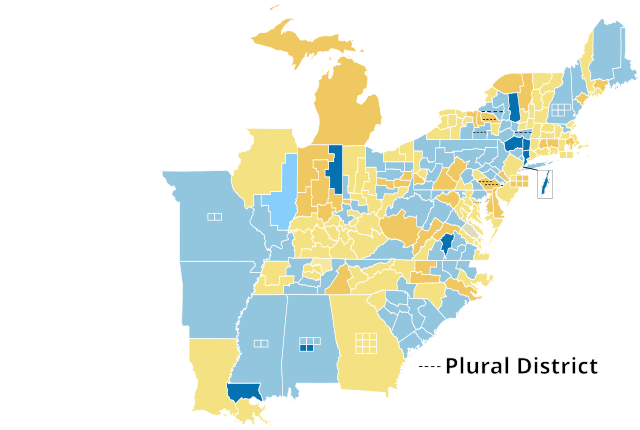

Prior to 1842, states elected their congressional delegations in a variety of ways. Most were elected in single-member plurality districts. But some were elected through multi-member districts, with bloc voting.

Bloc voting means voters could cast ballots for multiple candidates to fill multiple seats from the same district. If your district sent, say, three representatives to Congress, you got three votes to distribute among all the candidates running. The predictable result? The majority party would sweep all the seats and leave the minority party bereft of representation. Sounds a lot like today, come to think of it.

In the 1830s, many Democratic-controlled states moved to statewide multi-member districts with bloc voting, which made it easy for them to make a clean sweep of the entire congressional delegation. This meant that Democrats could win about two-thirds of the seats nationally with only a slight majority of the votes. This use of multimember districts was most definitely NOT proportional representation — it was the opposite!

This partisan move to bloc-voting multimember districts was a form of hyper-majoritarianism. Today’s aggressive partisan gerrymandering takes us right back to the 1830s!

Consider the parallels. Today, Republicans, unhappy with winning a mere two-thirds of the seats in Texas, are now redrawing maps to give them three-quarters of the seats. California, Democrats already control 43 out of 52 seats (more than 80 percent), but are now targeting upwards of 90 percent. New York and Illinois are also pushing for similar hyper-majoritarianism.

As my potted history below will show, the Whigs (then the other major party; Republicans didn’t enter stage right until 1854) responded by mandating single-member districts in the Apportionment Act of 1842 to guarantee their more urban constituencies would get at least some representation.

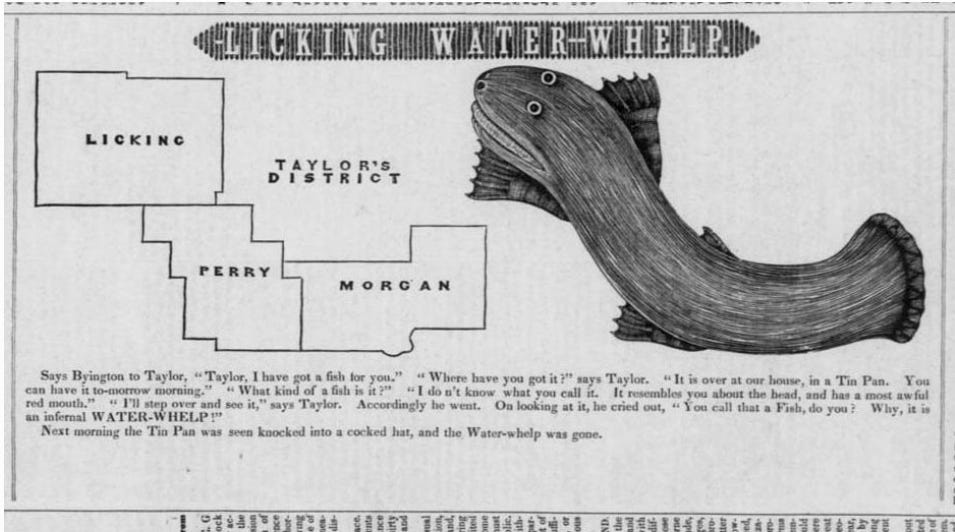

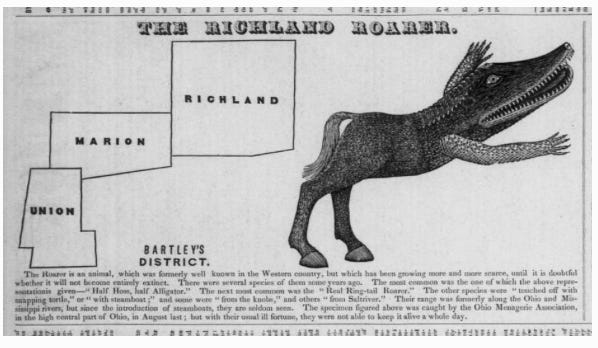

This single-member district mandate did make elections somewhat more proportional than bloc voting. But it was immediately prone to gerrymandering, as the 1842 newspaper cartoons I’ve included in this essay show.

The gerrymandering wars continued throughout the 19th century, getting very nasty at times. Starting around 1896, aggressive redistricting slowed down, as both parties had largely locked in their advantages in the states they controlled.

For the middle part of the 20th century, a politics of bipartisanship and ticket-splitting limited partisan gerrymandering, but did support incumbent-protection gerrymandering. Democrats appeared to have a permanent majority in the House, blunting the demand for partisan redistricting.

But in 1994, after 60 years of Democratic Party dominance in the House, Republicans won a majority, and control of Congress became less predictable, and higher stakes. Then starting in the 1990s, Polarization made partisan voting more consistent, giving lawmakers more predictability in the partisanship of districts. Competitive seats declined as parties sorted geographically.

And so the new gerrymandering skirmishes began, doom-looping their way into the current full-on warfare.

I have written a brief history of gerrymandering, for those who want more detail but don’t want to read a whole book on the subject. The tl;dr is that single-member districts have always been problematic, and gerrymandering has always been a problem in the United States. However, the current conflicts are a distinct flare-up.

And since today’s conflict has strong echoes of the gerrymandering wars that led up to the Apportionment Act of 1842, I figured it’s a good time for me to share the history from my book (pp 239-243 in the hardcover edition). It’s re-produced below. Stay tuned for some added commentary after the book excerpt.

The story of the Apportionment Act of 1842 (from Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop)

In 1842, the congressional Whigs faced a forbidding midterm election. The 1840 election had been a landmark success for the recently formed Whig Party. For the first time in its short history (the party organized in 1833 as the opposition to Jacksonian Democrats), the Whigs won unified control of government—the House, the Senate, and the presidency. The Whigs had nominated William Henry Harrison, an aging general whose "log cabins and hard cider" man-of-the-people appeal had helped him soundly defeat the incumbent Democrat, Martin Van Buren, who had earned the nickname "Martin Van Ruin" for presiding over hard economic times. But Harrison caught a cold at his inauguration. A month later, he was dead at sixty-eight, of pneumonia.

Things went downhill quickly for the Whigs. Vice President John Tyler (a former Democrat who had never fully bought into the Whig program) assumed office. The Whigs had campaigned on restoring a national bank as a response to the disastrous Panic of 1837 and the even worse Crisis of 1839. Twice, the Whig Congress approved banking legislation. Twice Tyler vetoed it. On September 11, 1841, Tyler's entire cabinet (except for the secretary of state, Daniel Webster) quit in protest. The congressional Whig delegation subsequently kicked Tyler out of the party and considered impeachment. This was not a great political strategy for the Whigs. State legislative elections in 1841 brought big losses for Whigs, foreshadowing a bad 1842.

At the time, congressional district sizes varied. Some states elected their congressional representatives in single-member districts, by plurality vote, as they do today. But by 1842, a quarter of members of Congress ran in multi-member districts. Voters chose as many candidates as there were seats. So, in a five-member district, for example, voters chose five candidates. The top five vote-getters went to Congress. This was not proportional representation; quite the opposite. This was hyper-majoritarianism. With one district for the entire state, for example, a party could convert a 55–45 statewide majority in party support to 100 percent of the state's congressional seats.

Democrats controlled many state houses in the 1820s and 1830s. They used their power to move toward multi-member districts, often converting the entire state into one large multi-member district. By one estimate, Democrats had rigged the system so that they could win two-thirds of House seats with just over half of the popular vote—a distortion that makes today's gerrymandering seem tame.

Ironically, Democrats' narrow dependence on winner-take-all multi-member districts left them more vulnerable to a Whig wave election in 1840. But in 1842, as congressional Whigs looked ahead to the midterm elections, these multi-member districts again posed a big problem for their party.

First, even more Democrat-controlled states were moving to multi-member elections, converting the entire state into one at-large district. In Alabama, for example, Democrats won all five seats in 1840, up from three seats in 1838, after Alabama converted the entire state into one multi-member district. Maine, where Democrats had won a state legislature landslide in 1841, had also announced a move to one multi-member district for the state.

Second, what multi-member districts had given Whigs in 1840 they were likely to take away in 1842. Whigs had swept all nine of Georgia's congressional seats in 1840. But state legislative elections in Georgia in 1841 went Democratic. That was nine seats Whigs were almost sure to lose.

Third, following the 1840 census, the 240-member Congress was responsible for reapportioning House seats to match the expanding US population, which was growing fastest in the states where Democrats had already locked in an advantage by moving to multi-member districts.

To mitigate their potential midterm losses, the Whigs came up with a plan: mandate the use of single-member districts. That would mean in states like Alabama, Georgia, and Maine (and several others), Whigs might avoid being wiped out. Since Whigs were still popular in the cities, they might still win the more urban districts.

The Whig Congress passed this single-member-district mandate as the Apportionment Act of 1842, on a near party-line vote. And for good measure, they reduced the number of House seats, from 240 to 223, to prevent Democratic states from gaining seats.

Democrats kicked and screamed in opposition. The Democratic senator from Georgia equated the single-member mandate with the French "Reign of Terror." A Democratic representative from New York complained that Congress had never done anything "so odious as this... [It is] an attempt to make the Government strong, and the people weak." But the Whigs had the votes.

In 1842, Democrats won back a 148–73 House majority. Whigs held on to the Senate, though. And while most states went along with the single-member-district mandate, a few Democratic states defied federal law and still used at-large districts. Then in 1846, Democrats faced a midterm backlash against an unpopular president of their own (James K. Polk). Fearing the clean sweep of a majority reversal, the remaining holdout Democrat-controlled states promptly moved to single-winner districts hoping to hold on to at least a few seats. Whigs still won back a narrow majority in 1846.

What can we learn from this history? The most obvious point is that parties and elected officials do what's in their perceived self-interest. Whigs thought they were correcting for Democratic abuses of power to help them win the next election. That's politics.

While Realpolitik drives most of the story, the change from multi-winner to single-winner districts in 1842 was also a change toward an objectively fairer system. Compared to at-large elections where a narrow plurality can give a party the entire congressional delegation, uniform single-member districts increased the likelihood of political minorities getting some representation, since different parties would likely have different geographical support within the state. Why should an entire state's congressional delegation go Democratic when 40 percent of the state's voters supported Whig candidates? That seemed objectively unfair. Even if Democrats complained, many acknowledged that single-member districts were objectively fairer.

This brief history is also a reminder that districting has long been contentious in American politics and that single-member plurality districts are politically, not constitutionally, imposed. It took a political act of Congress to mandate them. A century and a quarter later, in 1967, Congress reaffirmed the single-member-district mandate by passing the Uniform Congressional District Act. Fresh off the one-person one-vote cases and major civil rights legislation, some in Congress thought southern states might move to at-large elections to undermine minority representation. (Alabama had, in fact, moved to at-large, multi-member district elections for Congress in 1963, violating the single-member-district mandate but then went back to single-member districts in 1965.) To create multi-member districts today, Congress would have to repeal the 1967 law.

Lessons for today: reform is possible

So, could history repeat itself? By which I mean, could Congress change the rules of elections to stabilize the system and end this outrageous gerrymandering?

Let’s hope so. Because whatever this is, it’s ruining our democracy.

Moving to proportional representation is the peace treaty that can end the gerrymandering wars once and for all. (For a longer discussion of why proportional representation solves the problem, I refer you to my previous substack, an entertaining dialogue on inherent absurdities of single-member districts.)

Just as Congress mandated the single-member district in 1842 to eliminate the hyper-majoritarianism of multimember districts with bloc voting, the Congress of today must take the next step towards fairness and proportionality by mandating proportional multimember districts. This is the natural evolution of American politics.

Members of Congress can certainly justify partisan gerrymandering as necessary (the other side does it, so we have to!). But that doesn’t mean they like it. After all, any one of them could lose their district as a result. And there is nothing incumbent members of Congress hate more than having their district redrawn.

Ultimately, it should be in the self-interest of members of Congress to declare an end to the gerrymandering wars. And the only peace treaty is the one that outlaws the weapon that makes gerrymandering possible and profitable in the first place — the single-member district.

As a public school teacher, adjunct History professor, & independent exploring a run for Congress, I couldn’t agree more with this essay. Gerrymandering has turned our elections into rigged games, & mid-decade redistricting is proof the system is spiraling out of control. Both parties are chasing hyper-majorities instead of fair representation.

History shows we’ve been here before, manipulating district lines for power grabs in the 1830s led to the single-member district mandate. But even that reform has now become a tool for entrenching party control.

It’s time to break the two-party doom loop. We need structural reform, proportional representation, open primaries, and independent redistricting commissions, so voters pick their leaders, not the other way around. I’m not in this to protect any party’s power. I’m in this because our democracy should work for all of us, not just the political class.

Thank you for a concise and very informative article on the history of gerrymandering. I think most Americans really don't understand it in any depth. Personally, I believe the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929 has led to our dire partisan politics, as much, if not more than gerrymandering. We the People are woefully under represented with only 435 House members. We need to triple the size of the house, hence my PROJECT1305.org.