Slowly, then all at once: What Biden’s sudden departure tells us about how social change happens

Four lessons from a teachable moment

In relatively short order, Joe Biden went from the Democrats’ all-but certain presumptive nominee for president to ending his campaign for re-election.

What happened followed a classic social change dynamic: Change happened slowly. Then all at once.

If you want the blow-by-blow character narrative of how mounting pressure forced Biden to step aside, you will find it elsewhere. I’m more interested here in the broader social change lessons from Democrats’ top-of-the-ticket switcheroo. So here are four:

1. Known problems can persist for a long time — far longer than they should.

2. In moments of uncertainty, change is unpredictable, with consensus emerging, collapsing, and re-emerging.

3. Once the status quo becomes intolerable, it is hard to go back.

4. Change is only possible when there are clear and clearly better alternatives

Let’s dive in.

1. Known problems can persist for a long time — far longer than they should.

Known problems are surprisingly persistent. They stick around, even when everyone acknowledges a problem. Problems stick around not just because collective action is hard (it is!). Problems persist due to fear of speaking out, a lack of clear solutions, and skepticism that change is possible.

So, here I will take Biden’s insistence on running for re-election, despite his clear weaknesses as a candidate, as a problem for Democrats.

I am confident most prominent Democrats didn’t see him as a strong candidate . But few individuals saw any reason to openly state their opinions. Social pressure advised silence.

For example, when I publicly welcomed Dean Phillips’ October entry into the race and suggested Biden’s age was a liability, I was mocked.

I heard all the arguments for keeping quiet. Biden was going to be the nominee. So why highlight his problems? (As if by just ignoring his obvious flaws, they would somehow disappear and go unnoticed on a campaign? Interesting argument… People do have eyes.)

A few dissenting voices piped up intermittently. But mostly, it was a Private Truths, Public Lies kind of moment.

Private Truths, Public Lies is a book by the political scientist Timor Kuran. It presents a convincing theory that explains why people frequently opt to keep their opinions private, how widely held private opinions can remain undisclosed, and how the act of a few individuals speaking up can suddenly empower others to do the same.

For example, unpopular authoritarian leaders can often maintain power if criticizing the regime is dangerous. Individuals will not criticize the regime unless they are confident many others will support them.

Speaking up alone carries the risk of imprisonment and torture. But there is safety in numbers. Some people hold such strong views that they will risk such penalties (think Alexander Navalny). Sometimes, their courage inspires a cascade of followers.

Imagine ten people in a court, all opposing a regime. Without someone willing to be the first, silence will persist. Maybe one person speaks out first, but the next dissenter wants to wait until 20% of the court opposes the regime. In that case, nothing will change. There must be somebody willing to speak out if only 10% of people speak out.

But a dissenter’s threshold may change over time. Rising frustration with the regime may increase people’s willingness to act. So eventually a cascade might start, if the 20% threshold dissenter becomes a 10% threshold dissenter. But then again, if the regime has already executed the first dissenter who spoke out, the next dissenter might be less likely to act.

The point here is simple. A cascade of dissent depends on individuals’ willingness to act based on others’ actions. A small shift in a person (or a few) can lead to a major change, even if preferences remain the same. Like an avalanche, a small vibration can trigger a larger collapse.

A similar idea emerges from The Spiral of Silence, by Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann. Because most people fear social isolation, they keep what they believe are unpopular opinions to themselves. Thus, a fervent minority can silence the majority through intimidation.

I often pondered this dynamic when Trump was president. Privately, most congressional Republicans did not like him. But publicly, they were supportive. When Trump did something truly awful, I kept wondering whether there would be a cascade moment, when Republicans collectively spoke out against Trump. But there never was. A few Republicans would say something critical. Then they’d be isolated. The lesson to everyone else was: keep quiet. And pretty soon those most willing to speak up were gone, and the spiral of silence continued.

These spirals are common. They explain how problems persist despite wide agreement that they are problems — nobody wants to call them out. I previously explored this dynamic as ‘metastability.’

Leading up to the June 27 debate, it felt like we were in a stuck, metastable state. And then, Biden appeared confused and incapable of running a campaign. And everything changed.

2. In moments of uncertainty, change is unpredictable, with consensus emerging, collapsing, and re-emerging.

Within a few minutes of the June 27 debate, what had been settled became unsettled. What had been meta-stable became un-stable. What had been burdened became un-burdened. Moments like these offer multiple possible futures.

Still, after an initial prediction market drop in Biden’s chances, expectations stabilized. Biden reaffirmed his commitment to stay in, and Democratic leaders signaled clearly Biden would be the nominee, so all this talk of him stepping aside was just silly.

But still, the permission structure had changed. Now, it was okay to question Biden’s fitness for the campaign. Because now, serious people were asking questions. Suddenly, a dip in polling was not a blip, but a sign.

Now people were talking. And when people start talking, perceptions can change. These moments can fundamentally reshape collective judgments.

I will give you a slightly impish example of how this happens. When I was a mischievous college undergraduate, my friends played a little game while waiting for on-campus speakers to start their talks: Could we make the whole auditorium spontaneously applaud, even as the stage remained empty? We would start clapping, and if enough people followed, soon the whole audience would applaud.

If the people next to you start clapping, you might think they know something you don’t, and you might follow them. More applause leads others to think: maybe I should applaud, too. All kinds of fads and trends follow this “information cascade” pattern. Uncertain people seek guidance from their neighbors. The more people engage in a behavior, the more appropriate it seems.

In our game, the clapping would soon die down, when enough people realized there was no reason to keep clapping. These cascades can be fragile. But sometimes they lasted surprisingly long.

This is a common dynamic in cascades. They can move very quickly. But they can also reverse with equal speed. Indeed, there were moments when Democrats appeared to be cascading into overwhelming pressure for Biden to step aside. One statement of disapproval would follow another. Yet, there were moments when the cascade slowed and it seemed Biden could survive until the convention.

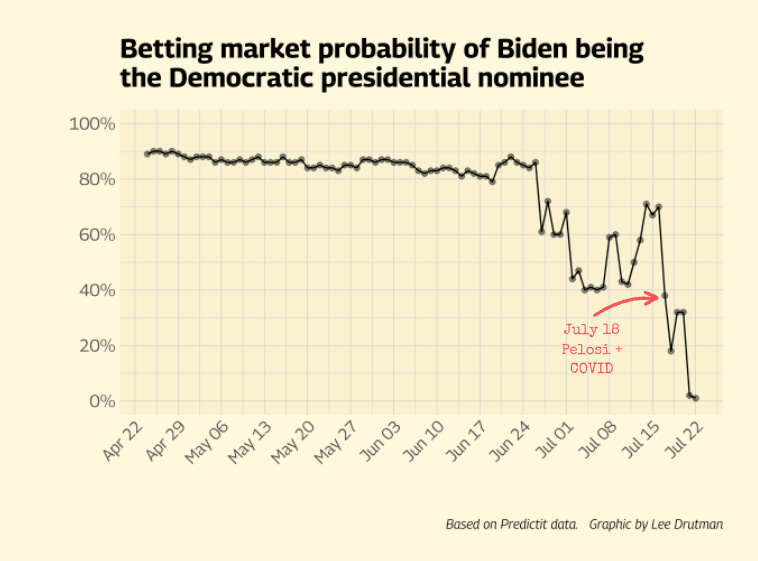

The betting market timeline reflects these ups and downs. But the conventional wisdom shifted quickly on July 18 when calls for Biden to step aside intensified, and it became clear that Nancy Pelosi wanted him to step aside. This was also one day after he tested positive for COVID. And at that point, the nomination hit a kind of phase shift. This often happens in moments of uncertainty. Possible outcomes fluctuate. But the system eventually resolves.

But once the system tips into a new state, a new equilibrium often emerges. Biden’s defenders feared chaos if he stepped aside. Within days, Democrats united. Kamala Harris was their new nominee. Cascades happen very quickly. They also often resolve very quickly.

Of course, quick decisions may not be wise. Sometimes, a collective rush to judgment based on a few initial leaders can lead to a collective mania.

When nobody knows what’s happening, the initial judgments of a few confident people can shape how everybody else responds. An audience can start clapping for no apparent cause. So, it’s important to not always rush to judgment.

Nonetheless, in many cases, a cascade is long overdue.

Still, cascades can often over-react. A status quo that holds for too long courts an over-reaction, just as prolonged bubbles in financial markets result in significant crashes. This is why central bankers raise interest rates to slow a fast-growing economy. All systems are dynamic. The more an unsustainable status quo continues, the more unpredictable the counter-cascade.

3. Once the status quo becomes intolerable, it is hard to go back.

One thing I heard repeatedly about Biden’s debate performance was that it could not be unseen. This is the language of contamination. An old Russian adage captures it well: "A spoonful of tar can spoil a barrel of honey, but a spoonful of honey does nothing for a barrel of tar."

In social change, there are moments in which it becomes so clear that the status quo is rotten and unacceptable that something must be done!

But what? Sometimes we are stuck with the tarred honey because we can’t find another sweetener. Sometimes contamination of the status quo leads to paralysis.

This takes us to the fourth lesson.

4. Change is only possible when there are clear and clearly better alternatives.

From the time of the June 27 debate until Biden’s announcement on July 21, Team Biden’s best friend was the fear of the unknown. Humans are risk averse. We are more likely to accept what we have, rather than gamble on an uncertain future.

Team Biden kept reminding everyone that Biden was the only person who had beaten Trump. Team Biden kept suggesting that if Biden stepped aside, Democrats would set themselves up for in-fighting, and who knows: they might wind up with a more divided party and an even less electable candidate. Harris also had notable weaknesses and was losing to Trump in most polls.

Team Biden could thus argue that any change to the status quo was risky. Uncertainty is the quicksand of social change.

Of course, one should be careful about changing the status quo. There are always unintended consequences. But there are also unintended consequences of maintaining the status quo. The world is complex, chaotic, and unpredictable. Nobody knows exactly what will lead to what. We do not live in a mechanistic universe.

Still, there are sometimes good reasons for caution: Maybe the status quo holds some wisdom. It has brought us this far. After all, Biden did win in 2020. But sometimes the current status quo may just be the result of a preexisting cascade that settled into a stable equilibrium in the past. But current circumstances can make that status quo unfit for a changed environment.

Nothing is static in politics. Past success may not guarantee current success. Politics is not classical physics, following stable laws of interaction. Similar to evolutionary biology, success in one generation may not ensure success in the next due to environmental changes.

Human thinking often gets hung up on past successes without considering if they were due to chance or past environments

This is a broad problem in our thinking. We over-learn from past success. We tend to resist doing things differently, even in a new environment.

It is often said that failure is the best teacher, because we learn more from our failures than our successes. That’s because when we fail, we seek alternatives.

The dynamic changes when the status quo comes to seem more risky than change. Or in this case, when the safe choice of sticking with Biden was no longer safe.

The search for an alternative helped us to imagine an alternative reality. And in imaging this alternative reality, we could see it as more possible. In this changed environment, the alternative — Kamala Harris for President, or an open convention — became more imaginable, and therefore less scary. More polling provided more information, and it felt easier to make a change.

When we take the time to envision a change, it starts to feel less risky. But too often, we hold onto the status quo, and envision the alternative in its most hyperbolic, chaotic, fuzzy framework. It took a while for many Democrats to fully inhabit an alternative world where Biden did step aside and Harris stepped forward or Democrats held an open convention.

But once an alternative became clear, and that alternative was clearly better, change started to feel inevitable.

In retrospect, change often seems inevitable. But in advance, it is anything but.

I think a lot about how political systems change. Typically, the change is small, on the margins, and the system dynamics hold. But now and then, there is something more like a phase shift.

In retrospect, big changes often seem inevitable. But at the time, they are hard to see. In 1913, many thought that economic interdependence had made war obsolete. Then came the Great War. In 2008, a “post-racial” America seemed on its way. Then came the racial backlash.

As I explored in a recent essay for the Niskanen Center, called How Democracies Revive, this linear thinking always misleads.

Time and again, we mistakenly predict that we have reached some new stage that will somehow last for centuries (e.g., we are at the “End of x” or “This time is really different” or Yale economist Irving Fisher’s September 1929 conclusion that “stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau”). Time and again, we mistakenly make straight-line projections about markets or demographics or politics, assuming that whatever trends have led us to this moment, they will continue indefinitely. But they never do.

One way to think about this is that history never moves in straight lines, but in waves, undulating in inevitable though unpredictable ups and downs of varying magnitudes. Yet, we as humans have a difficult time understanding exponential change. In calculus terms, we think in terms of first derivatives (steady rates of change), rather than second derivatives (changing rates of changes).

Thus, in periods in which change is slow, we should expect it will eventually speed up. And when change speeds up, we should expect it will eventually change direction. Or put another way, it is in periods where things seem all too quiet that we should expect trouble ahead. And it is in periods where it feels like we are rapidly careening towards trouble that we should expect a much more fundamental change ahead. But mostly we don’t, because our brains are not hard-wired to think this way.

But precisely because most of us don’t think this way, the future belongs to those who can squint ahead a few years and invest their time and energy towards productive and creative disruptions – just as those with the courage to buy during wild market sell-offs can get rich.

In moments of uncertainty, many alternatives become possible, but these periods are short. Pressure on Biden mounted when a critical mass of leading Democrats saw Harris as a better option.

As an advocate for electoral system change (specifically, proportional representation and fusion voting to create a more representative and responsive multiparty democracy), I think we are still in that first stage of reform: widespread frustration with the status quo. But alternatives are admittedly uncertain, and there is not yet widespread agreement.

Nonetheless, as the failures and problems of our current electoral and party system mount, more people are seriously considering alternatives. I hope we start to get comfortable with the alternatives. I hope we start envisioning them and thinking about how they might work.

At some point, we will hit a cascade moment. Transformational change can be hard to imagine right now, but a cascade moment will make maintaining the status quo even harder to imagine. I hope we make the change to a vibrant multiparty system sooner than later. The longer a problematic status quo remains in place, the more dangerous a cascade of over-reaction becomes.

Insightful piece on how group change can occur but, in this case, gives the group far too much credit. Biden standing down wasn't the result of a finally reached group consensus. It was made by Biden alone for reasons he will no doubt memoir. He wasn't fired or forced out by the group; Biden voluntarily quit. If he hadn't, the Democratic party would likely still be in the predicament it found itself in for 25 days following Biden's disastrous debate performance, due to inadequate party mechanisms or political will to deal with the crisis.

Very insightful piece. I was definitely one of those stuck in the status quo. I will need to use this experience to attempt to approach situations like this differently.