A deep tension haunts our politics.

1. On the surface, American politics is deeply calcified, stuck and hyper-polarized

2. Below the surface, American politics is rich with latent factions and repressed diversity.

Tense indeed. Are you begging for resolution yet?

Well, dig in. It’s time to grab your thinking shovel, put on your spelunking brain lantern, and excavate deep beneath the surface.

And at the end of the journey, here’s hoping you’ll have something fresh to say about politics at your next cocktail party.

1. The one-dimensional battle within the Republican Party

Why the Not-Trump faction can’t win, and why the MAGA base can win despite being a minority.

We start close to the surface, with the latest New York Times/Siena College poll showing Trump with a commanding lead in the Republican primary (54 percent support, way ahead of DeSantis at 17 percent).

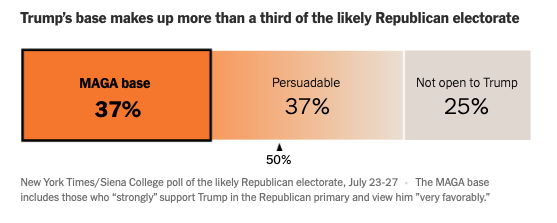

But dig deeper, and it starts getting labyrinthine. More than a third (37 percent) of the Republican electorate is the “MAGA base” — these are the always-Trump voters.

This number is slightly larger than the 33 percent of Republican voters who in January described themselves more as a supporter of Donald Trump than of the Republican Party, or the 28 percent of Republicans who said they would support Trump even if he ran as an independent.

In other words, Trump has a solid core of support somewhere around a third of the Republican party.

So, if we assume that 45 percent of the overall electorate is Republican, then simple math gives us a core Trump/MAGA base lies somewhere between 13 percent and 17 percent of voters. This is the kind of support range that European far-right parties typically enjoy.

Continuing to look below the surface, the plight of the not-Trump right comes into fuller light. A quarter of the Republican electorate is “not open to Trump.” They are more moderate in outlook.

And as a quarter of the Republican Party, they are at a tremendous numerical disadvantage. If they were their own party, they’d represent about 11 percent of the electorate.

And then there is the soft middle of the GOP — 37 percent in the New York Times poll — who are persuadable. They are less committed one way or the other, and more likely to follow whichever way the political winds are blowing. They are, for the most part, ordinary partisans. If the winds blew against Trump and his brand of illiberal extremism, most would likely follow.

But for the winds to blow against Trump and Trumpism, somebody will have to start changing the weather. And herein lies the dilemma for the center-right: Attacking Trump directly is a losing strategy given the current Republican coalition. Yet, not attacking Trump just solidifies the Don’s support within the coalition, and makes it appear as if there is no real alternative.

Again: 37 percent of the Republican electorate is hard-core Trump. At least half of the middle group is at least somewhat supportive of Trump. So a center-right candidate simply can’t alienate too many of these supporters and still win a majority in the party. Whereas Trump can easily win the primary without the anybody-but-Trump moderates.

Given Trump’s pending gauntlet of criminal charges, DeSantis’s best strategy is to publicly support Trump while privately hoping the pile of prosecutions crater Trump’s support. Hence DeSantis has tried to be like Trump, but not Trump. A hard tightrope act for anyone to pull off Especially Ron DeSantis.

And as for the “not-Trump” Republicans ” — there is no path to the majority without being a bit Trump-y. Unless, somehow, Trump flounders, the “MAGA lane” gets super-crowded, and a single moderate emerges. In other words, probably never.

But, even here, this unlikely victory would be but a treasure chest filled with vipers. Should Trump lose, many of his supporters would threaten to sit out the election. They would make insane demands.

A more moderate GOP standard-bearer would struggleto bridge the unbridgeable chasm between appeasing the “base” and assuring the “moderates.” Into the abyss we go. The only viable strategy will be the same: attacking Democrats as even satanic socialists who hate America and everything it stands for.. Nothing unites like a common enemy. Doomier and Loopier we go.

This same intra-party struggle applies as well to Senate and House elections. It is hard for Republican moderates to win primaries, because there are simply not enough moderates who vote in Republican primaries. This is true in states with open primaries as well as closed primaries. (And once again, independents are not the same as moderates). And even if moderates do win (and they sometimes do), they are very limited in how much bipartisanship they can evince. They have to get re-elected, after all.

And Republicans have to get re-elected in the most MAGA-ish parts of the country. Because Democrats and Republicans are geographically split, Republicans only represent the most Republican parts of the country. The moderate Republican voters are more likely to live in the more liberal and moderate parts of the country — the coasts, the northeast, the cities. These places elect Democrats. Core MAGA is strongest in the places that elect most Republicans to Congress. This is why the Republican congressional delegation has to behave so MAGA-ish.

The upshot of this is simple: Core MAGA is a political minority in this country. Probably around 17 percent of the electorate. Yet, because of the ways in which the US party system operates, 17 percent can win majority control. The basic formula is simple: Just be a plurality inside of one of the two major parties.

The Core MAGA (37 percent of the GOP) is not that much bigger than the Not-Trump-Moderates (25 percent of the GOP). But the Core MAGA can dominate the party without the Not-Trump-Moderates. The reverse is much harder.

In a multiparty system, the Not-Trump-Moderates could have their own party. They could have their own identity. And they could go hard against core MAGA, knowing they are never going to win those votes and don’t want them. Maybe the Not-Trump-Moderates could even find some common cause with some of the more conservative Democrats and form their own party. This is the kind of thing we see in democracies that use proportional representation. It’s also something we would see if we re-legalized fusion voting widely.

More possibilities abound. But not on the surface given our current electoral rules and party system. Gotta keep digging.

2. Digging deeper: Two dimensions, four quadrants, five parties

The possibilities expand

Echelon Insights is out with its “Quadrants 2023” report. I love this report, because it combines two of my favorite ways of looking at the electorate: 1) breaking out the economic and social issues as separate dimensions so you can have four quadrants, and 2) asking voters what parties they might prefer if we had more than two.

So here’s my highlight reel of the slide deck accompanying the report.

First the beloved scatterplot in two dimensions (x axis is economics, y axis is social issues). Voters are somewhat ideologically diverse. Also: 61% of voters are left of center on economics, but 51% of voters are right of center on social issues. And true libertarians are rare. (This is very similar to my 2017 Voter Study Group report on the 2016 election)

Next: what if we had five parties? I have a slightly different view of how a multiparty system might look (with six instead of a five), but the Echelon partisan quintet is intriguing. Here, the Acela Party holds the balance of power. If the Labor Party is the largest party, the logical governing coalition would be the Labor-Green-Acela coalition — a center-left coalition.

For Station Eleven fans (and everyone else), note that the 11 percent the “Acela” Party gets is the same number (11 percent) we see for the “not open to Trump” Republicans. These are different surveys, but I’d guess there is at least some overlap. At the very least, it suggests something like an 11 percent political center — not anywhere close enough to win elections or its own, and too small to be a major player in either party.

I also like how Echelon combines the multiparty preferences with the scatterplot. For me, the super-interesting takeaway is how the alternative party preferences break down somewhat along the expected partisan and ideological lines, but also somewhat not.

Under a different party system, in which different parties emphasize different issues, voters might sort themselves slightly differently. Things are less stuck they they might look in our one-dimensional, two-party surface world.

I recommend the whole slide deck. But for me, the big takeaway is that the surface level hyper-partisanship of our politics is holding back more possible diversity and coalition-building beneath the surface. If only there were some way to unleash it…

3. Even deeper: Peering into the 5-dimensional issue space

The possibilities expand further

Still with me? Of course you are, or else you wouldn’t be reading these words. Good. Let’s venture even deeper.

We often look at these latent parties from the perspective of voters and public opinion polling. But what if we took a different approach, and thought of parties as coalitions of interests?

That’s the approach from a new paper, just released by the New America Political Reform program: “The Multiplicity of Factions: Uncovering Hidden Multidimensionality within Congress and among Organized Interests.”

In this paper, four scholars (Jesse M. Crosson, Alexander C. Furnas, Geoffrey M. Lorenz, and Kevin McAlister) introduce a fancy new methodology, Bayesian nonparametric estimation procedure (BPIRT), to look at the dimensionality of interest group positions on bills. Okay, that’s a mouthful.

Here’s the upshot: Our politics might actually be five-dimensional, instead of one-dimensional. But the two-party system collapses everything into a single dimension. As they write, “collapsing legislative disagreement into a single dimension—which two-party competition often does—may hide a lot of particulars about who is really disagreeing with whom on any given issue.”

So, by looking at the ways in which interest groups coalesce around different bills, they find there’s a lot more “dimensionality” to our politics. That is, different groups form different coalitions on different issues. But these dimensions are essentially forced into two coalitions, so that voters don’t get to see much of them (beyond the occasional intra-party fight), and certainly don’t get the opportunity to express preferences across multiple dimensions or choose different bundles.

But if we elected our Congress under a different set of rules, with more parties?

In such a system, any group interest (or coalition thereof) that reflected the interests of enough voters to win seats in Congress could conceivably form its own party. The diversity of interests that currently manifests in intra-party factional battles could then be expressed through a multitude of parties. In such a system, voters could choose the party that most closely reflects their interests rather than the least objectionable coalition. These parties would, in turn, have strength in Congress proportional to their support in society and could form governing coalitions on that basis.

Instead, we are stuck with a political choice set that forces everyone to pick sides. As they write, "by forcing complex conflicts onto a single dimension, the parties ensure that interest groups must be influential within one of the two parties to influence policy and so are incentivized to choose a camp. This partitions a complex web of political conflicts into two internally fractious sides.”

4. Planting a New Garden of Democracy

How to tap the rich soil below so democracy can flower again

Now back to the core tension. Lots of rich diversity lies below the surface. But contrast that to the surface reality: another electoral old-white-man grudge match. The 2024 election will almost certainly be an exact repeat of the 2020 election. Only four states are genuine toss-ups for the presidential election, along with only a handful of Senate seats, and maybe at most 10 percent of House seats.

Just as 2022 basically recapitulated the results of 2020 (no incumbent Senator lost, only one incumbent governor lost, and the House flipped mostly because of redistricting), so it’s hard to imagine more than a tiny shift in 2024. But in a knife’s edge election, even a tiny shift is highly consequential. Hence the panic about No Labels.

But… What if I told you there was a simple solution to:

1) solving the No Labels spoiler problem;

2) empowering that ~11% center-oriented slice of the electorate that appears to be pivotal to the balance of power; and

3) building towards a multiparty democracy that would create more flexibility and fluidity in our political system to break the brittle calcification?

Too good to be true?

If you’re a regular reader of this newsletter, you know what I’m gonna say for 2024. The answer, of course, is fusion voting.

As Beau Tremitiere and I wrote in a recent piece for The Bulwark about the No Labels threat:

There is a much better way to rebuild the political center and to give Americans more choices at the ballot box: fusion voting, which allows third parties to cross-nominate candidates without spoiling, giving voice and power to the millions who don’t like either the Democratic or Republican parties. And it has a long and rich history in the American political tradition.

With fusion, a centrist party could nominate whichever of the two major candidates was more moderate, incentivizing further moderation and providing a platform for moderate voters to signal why that candidate earned their support. Rather than putting forward a doomed candidate, a centrist party and its supporters could use their leverage to elect the better of two viable options. Crucially, fusion would allow a centrist third party to become a durable and influential part of our politics for years to come. With a political home and identity for the millions of voters stranded between the two major parties, we could have a renewed and powerful political center—precisely what No Labels claims to want.

Is this possible? Absolutely. This strategy is viable now in several states that allow some form of fusion voting in presidential elections. And efforts are underway to re-legalize fusion voting in New Jersey and other states. If No Labels were to invest even a fraction of its $70 million war chest in this direction, they could actually advance their goals of reducing extremism and making our politics more representative. On their current course, No Labels will instead spend a fortune with little to show for it—except putting American democracy in even greater peril.

But going even further… Let’s imagine what 2024 would look like if fusion voting were widely legal. In deep red and deep blue states, No Labels could put forth its own contenders for the presidency. However, in the pivotal swing states which hold the key to election outcomes, it could make the prudent choice of cross-endorsing the sole candidate who advocates for free elections and the sanctity of law - President Biden.

This strategy could attract a broad coalition, spanning from Republicans disillusioned with the MAGA agenda to independents and conscientious Democrats, while not requiring a straight-line Democratic vote from everyone.

And from there, we could begin to build out the multiparty democracy we need to represent the diversity of America, and break the two-party doom loop.

Glad you dug this all enough to make it all the way to the bottom.

And here at the bottom, we find my Bottom Line: On the surface, politics feels flat and stuck and dirty. But dig a little deeper, and the possibilities expand.

Not clear to me why our "lesser of two evils" problem is improved by simply announcing a new party which then gives its imprimatur to the l.o.t.e. Voters still have the same choice to make. Perhaps the centrist party could put out info explaining *why* one candidate is the l.o.t.e., but I suspect that this just gets lumped in with his/her own campaign in the voters' minds, and the centrists regarded as a disguised wing of that party. As your last couple of paragraphs well illustrates.

To get out of the one-dimensional bind we need to reform the election system that put us into it. Systems such as Ranked Choice voting and Proportional Representation give voters the chance to actually vote for and elect candidates who represent their multi-variant interests.

Agreed 110% that politics is actually multidimensional and gets squashed into a false one-dimensional line by our two party system. This is a big problem that causes closed minds and ever-increasing polarization.

Some papers:

Kousser 2016 - Reform and Representation: A New Method Applied to Recent Electoral Changes (Elected representatives are polarized while voters are not. Changing to top-two runoff voting does not fix it.)

Klar 2014 - A Multidimensional Study of Ideological Preferences and Priorities among the American Public

C. Alós-Ferrer (Carlos) and G.D. Granić (Georg Dura) 2015 - Political Space Representations with Approval Data, Electoral Studies , Volume 39 p. 56- 71 (German politics is at least 4-dimensional)

"It’s also something we would see if we re-legalized fusion voting widely."

I don't see how. My jurisdiction has fusion voting and it has little to no effect on the two-party system. I try to always vote on a third party line when I can, but pretty much no one else does, and the third parties are either invisible rubber stamps for the two main parties or they refuse to participate in fusion at all and continue to act as spoilers.

The fundamental cause of the one-dimensional two-party system is voting systems that only count first-choice preferences: Plurality voting, Open Primaries with top-two runoffs, Supplementary Vote, Ranked Choice Voting, and hybrids like Top Four or Final Five, etc.

All these systems have the same flaw of only allowing you to express support for one candidate at any given point in the counting process, which means they suffer from vote-splitting, center squeeze, and spoiler effect. We work around vote-splitting by holding party primaries, but those result in nominees who only represent part of the population, rather than the whole. We work around the spoiler effect by making it hard for third parties to get on the ballot, excluding them from debates, and discouraging honest voting, and this perpetuates a two-party system.

The real solution to these problems is to adopt better voting systems that consider all voter preferences when choosing the winner, and thus tend to elect a consensus candidate that best represents the entire electorate. (STAR Voting, Condorcet systems, Approval-based systems, etc.)

Then, when the electorate is freed from the rigid polarized one-dimensional two-party system, they are more able to listen to other points of view, change their minds, and move around in the true multidimensional ideological space, and these good voting systems will follow them, and continue to elect the candidate who best represents their new position.