How did American democracy become a broken game without winners? And what should we do about it?

Support for democracy in America has fallen to alarming lows, even as voters desperately seek change. Proportional representation could re-energize our democracy

(This is the first in an anticipated multi-part series reiterating my case for proportional representation)

Over at the New York Times, I’ve got a big new piece on proportional representation, “How to Fix America’s Two-Party Problem”, with the brilliant Jesse Wegman (a member of the Times editorial board).

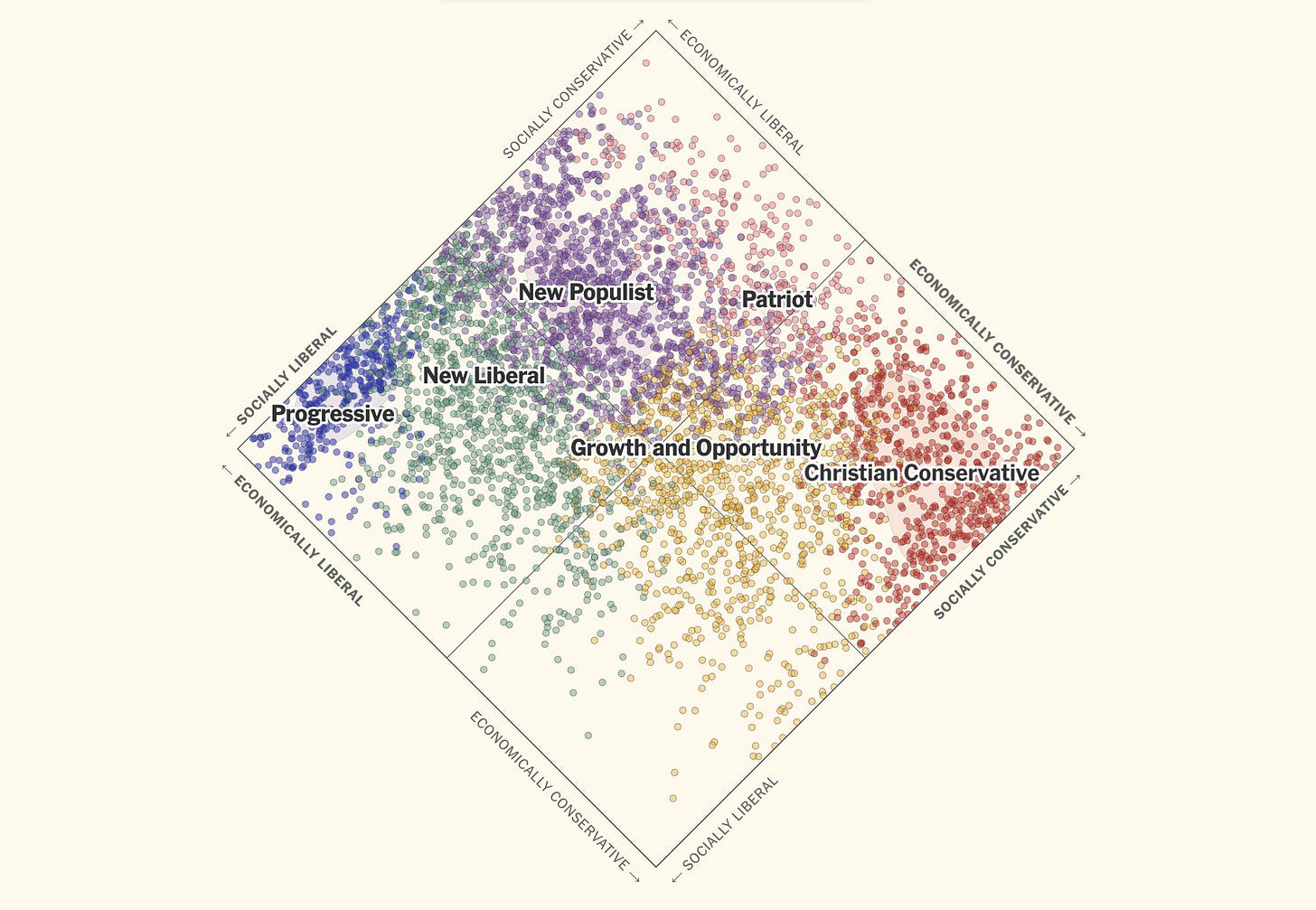

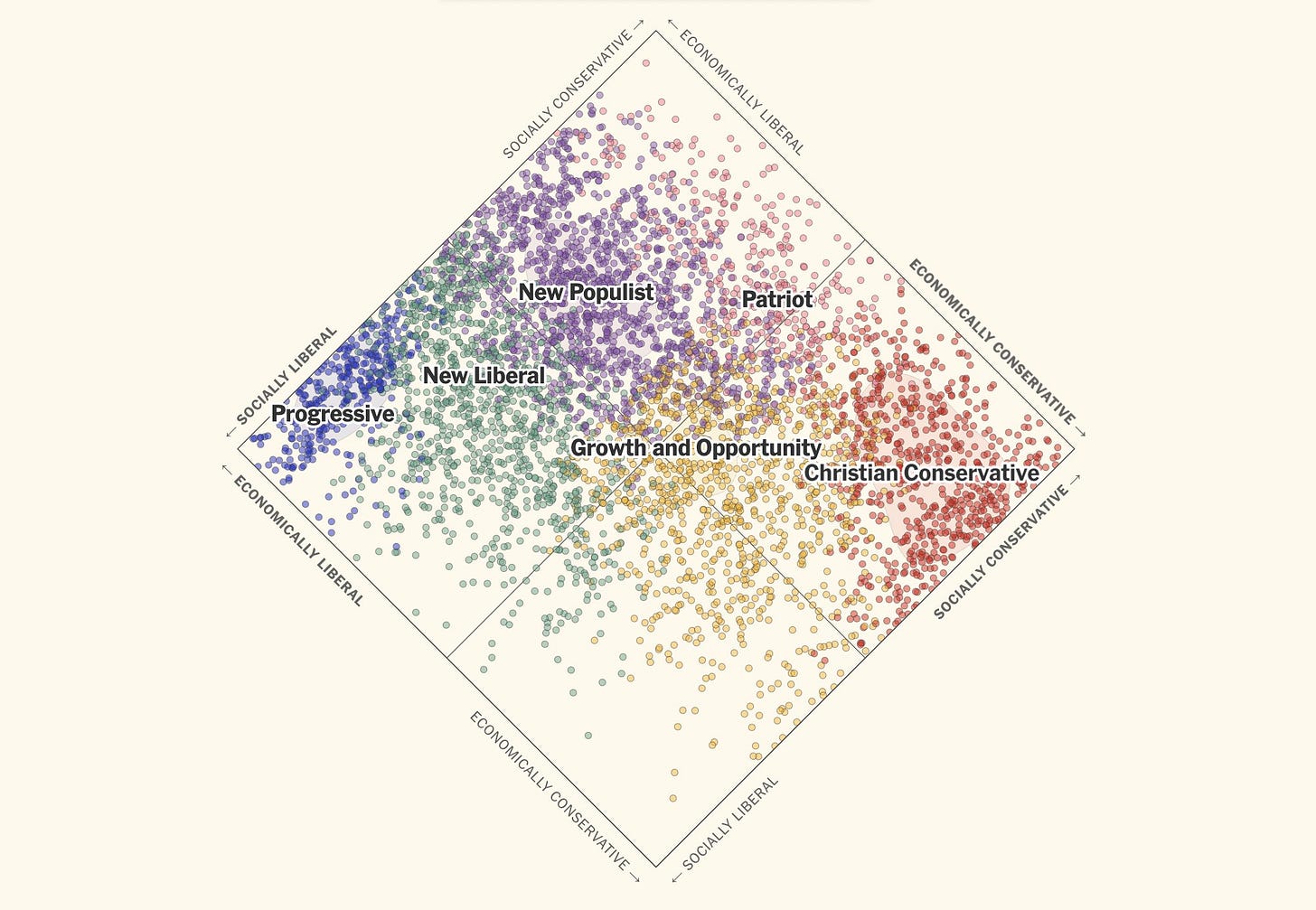

The Times piece makes many arguments that may be familiar to readers of Undercurrent Events. But it does so with an unparalleled visual verve, thanks to the very talented graphics team at the Times. It also offers my latest best-guess hypothesis of how a six-party system might reshape representation in Washington D.C. (based on some existing survey data and latent elite divisions).

The Times piece should stand as the if-you-read-one-thing-on-proportional-representation-read-this-thing piece.

But my writing here is admittedly more discursive and exploratory. So I plan to write a series of posts, starting with this one, to explore the crucial premises and principles of a healthy modern democracy in a country as large and diverse as the United States — and why I see proportional representation as key to achieving them.

This series will, of course, address the skeptics who worry that proportional representation would make things worse. I appreciate the skepticism and welcome the debate. After all, the choice of an electoral system is arguably the single most consequential institutional choice a democracy can make, since elections are the focal event in modern representative democracy.

But we have to be equally unflinching about the dangers we are facing under our existing electoral system, and the risks of keeping the failing status quo - or only making marginal changes in hopes of mostly preserving the deeply unpopular status quo.

I’ve already written twice (here and here) on the central importance of healthy political parties in maintaining a healthy democracy. We need stronger and healthier parties with real local presences that go beyond a single leader. So, I’ll take that first premise here as a given.

My words below will focus on the current state of U.S. democracy and put us in some (unflattering) comparative context. I’ll also argue why doing nothing is not an option.

Let me also be clear about expectations here: proportional representation won't solve every problem in modern democracy. It is neither panacea nor silver bullet (these are straw-man claims critics like to toss at me.). But among all available systems, it offers the most effective framework for managing collective decision-making in diverse societies like ours.

Support for democracy in the United States has been steadily declining for decades. This is very bad news.

The following chart tracks support for democracy across OECD countries over the past three decades.

Support for democracy in the United States has fallen from above average among OECD countries to decidedly below an overall average that has remained flat over this period.

I've highlighted several key countries in this chart for illustration. The northern European nations (Denmark, Sweden, Germany) show continued strong public support for democracy, despite some recent party system volatility. All use proportional electoral systems. Notably, support for democracy in these countries actually increased after the 2008 financial crisis - a finding that challenges some common narratives.

France and Canada - both using single-winner majoritarian elections - remain in the middle of the pack, where they've consistently stayed.

The US trajectory mirrors South Korea's, which recently made headlines when its president declared - then swiftly undeclared - martial law amidst rising two-party polarization.

Public support for democracy in the United States now sits closer to Turkey's current level than Germany's.

You can find the complete dataset here. The data come from political scientist Christopher Claassen, who has produced an impressive, rigorous series of academic papers examining democracy support. His work has developed what I consider the best index of democratic support, drawing from multiple surveys.

Crucially, Claassen found that support for democracy differs from satisfaction with democracy. Support represents a more principled attitude, mostly resilient to fluctuations in government performance and effectiveness. Satisfaction proves more mercurial, reflecting economic conditions and current leadership.

So when voters oust incumbent parties across Western democracies, it doesn't necessarily signal eroding support for democracy. Evidence suggests that the very ability to try new leaders and parties in addressing challenges actively sustains democratic support, even as satisfaction fluctuates.

Significantly, Claassen found that declining support for democracy, rather than satisfaction, most reliably predicted democratic backsliding. That’s why the US trend is very worrying.

Democratic backsliding is undoubtedly complex, with public support being just one factor - leadership behavior matters most (as Larry Bartels argues in his excellent recent book, Democracy Erodes From the Top). But declining democratic support enables leaders to violate democratic norms without fearing electoral consequences. These norms include respect for political opposition, acceptance of electoral defeat, and tolerance of dissent - the basics of liberal democracy.

Donald Trump's impending second inauguration puts a triple exclamation point on these backsliding concerns.

If democracy was at stake in 2024, why didn’t it win?

Throughout the 2024 election, Democrats kept telling me that democracy was at stake. But the more I heard this argument, the more hollow it began to sound.

First, I was never clear what Democrats — who were supposedly defending “democracy” — were actually defending, other than a deeply unpopular institutional status quo.

Democrats could have offered exciting reforms to fix our broken system. They could have painted a vision of truly representative and responsive democracy through reform. But instead, we got some vague paeans to freedom and liberty as crucial democratic values. All while Democrats told voters that exercising that freedom to vote for anybody but Democrats would, check that, be the end of democracy. Puzzling.

Second, I wondered: Did we even have a democracy if so few elections were actually competitive? Yes, the national balance of partisan power hung on a wafer-thin vote difference. But in about 90 percent of the House elections in 2024, the winner was a foregone conclusion. Only 45 of 435 House districts were close enough to be races “to watch” . At the state and local level, it was even worse: more than two thirds of elections had only one candidate. This lack of competition resulted directly from our antiquated system of single-member districts alongside geographically polarized parties. Almost all definitions of democracy involve robust competition. So what, exactly, were we defending?

Third and most troublingly, I kept wondering if we even really had a democracy if it depended on one party — Democrats — holding power in Washington, as I kept hearing it did (from Democrats). After all, a foundational political science definition of democracy is that “democracy is a system in which parties lose elections.” By this definition, then, we did not have a democracy anymore as of last year, since we kept hearing that, in fact, it would not be okay if our side lost. Also puzzling.

All of these confusions emerged from our deeply polarized two-party system built out of single-member districts, which left us with only two options nationally and only one viable option in more than 90 percent of the actual elections.

Why do we care about democracy anyway?

When it works well, democracy through regular elections is a powerful system for maintaining civic peace. We often take for granted the value of not needing to constantly worry about defending ourselves against our neighbors or our rulers. It frees up a lot of time for other, more rewarding and productive activities, like family and work and leisure.

Throughout history, successful democracies have held this internal peace by harnessing human passions for competition and cooperation into productive political tension. This was the insight that powered the Constitution — the idea, as James Madison famously put it in Federalist #51, that “ambition must be made to counteract ambition.” By dispersing authority across multiple institutions, tyranny could be avoided. Democracy dies in concentrated power.

For a long while in the US, this system worked reasonably well. But that was when our politics was more localized and our parties contained overlapping multitudes. Today in the US, this once-dispersed power has calcified into a bitter concentrated deadlock. The current era of highly nationalized and polarized parties is cracking the aged structures of a political system that only works with localized and non-polarized parties.

While the history of democracies has shown that Madison was right about the dangers of over-concentrated power, it has also demonstrated that too much dispersion also poses risks through gridlock and incapacity. Too many veto points make an energetic and effective government impossible.

Somewhere between the extremes of too concentrated and too dispersed lies a happy balance. In this felicitous middle, political leaders can build majority coalitions to get stuff done. This is what we need to aim towards.

Crucially, this middle space means that all coalitions must be fleeting. When the same divisions get entrenched, the same conflicts between the same two coalitions repeat until they become bitter and poisoned. This is something Madison and other framers constantly warned about.

As long as majorities remain fluid, new possibilities and energy can periodically re-energize the human optimism necessary to take on new problems. This is the ever-present possibility that drives democracy forward, periodically re-kindling the persistent hope that things can get better. It’s this hope that drives us to tackle the hard problems and keeps us committed to the system of regular elections.

Rotation of power is key to healthy democracy

With striking regularly, public opinion in democracies steadily turns against the party in power. Political scientists call this “thermostatic politics.” Governing parties face a “cost of ruling” — they pay a popularity price for being in charge, because they become responsible for all that goes wrong on their watch. And because our innate negativity bias means that bad is stronger than good, we attend more to failures than successes. Failures pile up. Successes fade from memory.

This explains why incumbent parties around the world got wiped out in 2024 — and are likely set for further wipeouts in 2025. A lot has gone wrong lately! And yes, most of it was beyond the power of individual leaders. Post-COVID inflation has been a beast.

The history of elections makes clear that voters regularly want “change.” (Think of how many winning campaigns have been waged on some vague promise of “change”) This is a good thing; rotation in power is central to the legitimacy of democracy. Parties need to lose elections from time to time. Nobody should get too entrenched in power. Otherwise, corruption sets in, like the predictable mold that feeds on days old left-out bread.

Thus, democracy rests on an odd duality of the human spirit: despite repeated disappointments, voters summon fresh optimism with each election cycle. This regenerative capacity - the persistent belief that change remains possible even after past hopes have been dashed - distinguishes democracy from other systems of government. Where autocracies breed resignation, democracies regularly kindle hope.

And sometimes, things really do get better! Challenger parties sometimes have better ideas, and competition drives innovation in politics, as it does in business. We need these challenger parties, both to hold existing powers accountable, and to call forth new solutions and new possibilities from time to time. And sometimes, we need new challenger parties to replace the old challenger parties.

Historian James Kloppenberg calls this cycle of optimism and disappointment an “ineluctable dialectic” — as he writes in his excellent book, Toward Democracy: The Struggle for Self-Rule in European and American Thought,

“Democracy, as it expands, breeds optimism and disappointment, euphoria and despair in an ineluctable dialectic… Democracy, by always kindling hopes for change, forever feeds frustrations, in part because of the tensions between democratic principles, and in part because our struggles to resolve certain problems and inevitably creates others”

But what happens when that possibility seems to vanish? What happens when it feels like the electoral mechanism is stuck and there is no way to channel some new energy into politics?

It is starting to feel that way here in the United States. The sense of resignation I sense among my liberal friends is something different. It’s a turning off rather than a hope for a better turn next time.

Still, it’s important to keep in mind that the 2024 election was not an enthusiastic mandate for Donald Trump and the Republicans. It was instead a resigned shrug. As Michael Podhorzer astutely explained in a recent essay (How Trump “Won”) on his substack,

The defining feature of American politics this century is that neither party can “win” elections anymore; they can only be the “not-loser.” Only thanks to the two-party system can the not-loser be crowned the “winner,” since there is no way to fire the incumbent party without hiring the opposition party. Yet political commentators keep confusing shifts in the two parties’ electoral fortunes with changes in voters’ basic values or priorities. A collapse in support for Democrats does not mean that most Americans, especially in Blue America, are suddenly eager to live in an illiberal theocracy.

Consider that only once before in American history have three consecutive presidential elections seen the White House change partisan hands, and that nine out of the last ten midterm or presidential elections have been “change elections,” in the sense that either the presidency, the House, or the Senate changed partisan hands, which is completely unprecedented.

No wonder Americans are losing support for democracy. They keep voting for change, yet little actually changes. They keep feeling like the system is unfair and broken. In the U.S., a dangerously growing share of Americans don’t like either party and feel constantly stressed out by our politics. That’s very bad if you think democracy is a good system.

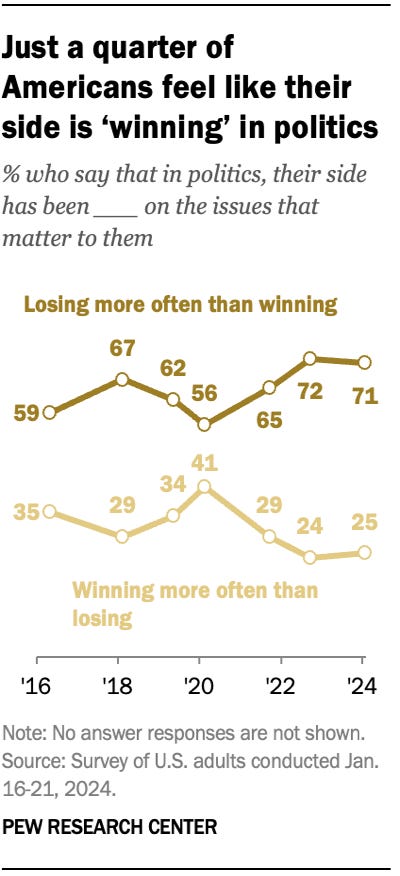

For almost a decade now, the overwhelming majority of Americans have said that their side is losing more than it is winning, even as power goes back and forth. That’s the sign of Americans slowly losing support for our democratic system.

How do we get out of it? Big electoral reform, of course.

This is where I keep coming back to the importance of electoral reform that opens up the political system to multiple parties, specifically moving to a system of proportional representation and, for necessarily single-winner elections, fusion voting. It’s time for some new energy, already. We’re all tired of the same old grudge matches.

The problem with our two-party system is that every election reifies the same artificial binary, and then confers a “mandate” on a narrow one-percentage point victory. And then, in the next election, a small percentage of voters abstain, another small percentage switch parties, and a new mandate gets proclaimed. But functionally, the national government mostly remains stuck, and discontent continues to burble up like volcanic lava. If this unresponsive calcified system is “democracy,” then what are we even defending anymore?

This shrug of resignation that even I start to feel worries me. This election felt so high stakes back in October. But now, are we all just receding back into our private lives? And passively waiting around for thermostatic politics to kick the Democrats back into power as the next “not-loser”? That kind of resignation paves the way to authoritarianism.

In future posts in this series, I’ll more directly address the skeptics who worry that implementing proportional representation would make things worse. I acknowledge their concerns, but I think they are misplaced. But I also acknowledge that the future is and always will be an unknown territory, and we can only guess what it looks like.

There are always unintended consequences with any change. But there are also consequences to doing nothing, or continuing to do the same thing over and expecting different results. Perhaps the most dangerous consequence is falling into learned helplessness and giving up.

I actually believe we can get big transformative electoral reform here in the can-do United States — otherwise I wouldn’t be devoting so much time and energy to it. And I feel this more strongly than ever: We need to unleash some new creative optimism to keep us believing that things can get better. Because sometimes, things really do get better.

Thanks for your great and as you say beautifully presented article! You worry that skeptics will say that such proposals go too far and might break the current system; I'd argue that in fact proportional representation does not go far enough!

Since I love the idea the way you are opening constitutional issues up for real, concrete debate, I took a leaf out of my late Dad Maurice Pope's book The Keys to Democracy: Sortition as a New Model for Citizen Power and pulled together what he might have written in response to your piece:

https://open.substack.com/pub/hughpope/p/proportional-representation-a-cure?r=295n2&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

New Liberals for proportional representation!